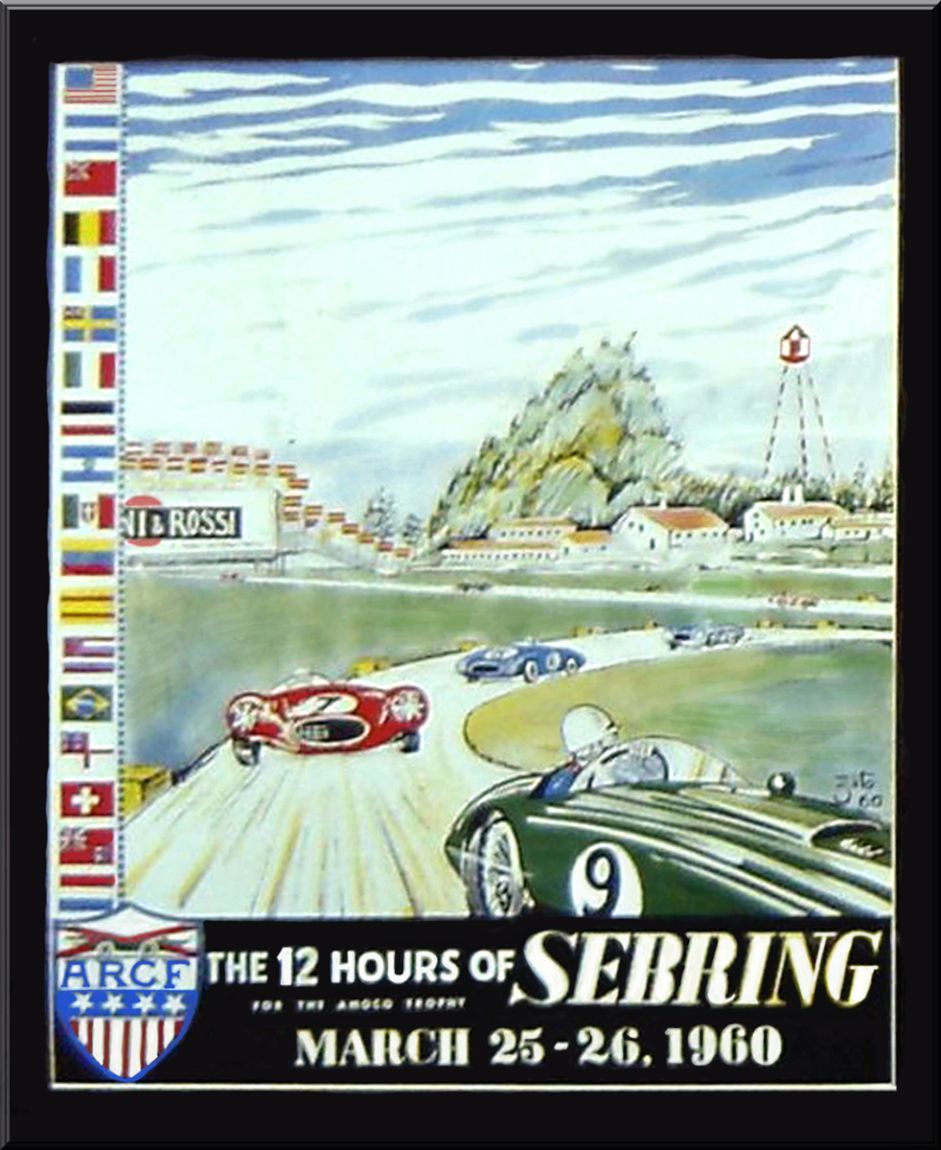

1960 Sebring 12-Hours Grand Prix – Porsche Racks Up Their First Overall Win at Sebring

By Louis Galanos | Photos as credited

From 1954 to 1959 Porsche of Germany had managed to have one or more of it 1.5 or 1.6 liter race cars finish in the top ten at the Sebring 12-Hour Grand Prix of Endurance, which many considered the premier sports car race in North America.

However, during those years as also-rans, the coveted first overall trophy eluded Porsche consistently despite their proven reliability on the track. Larger displacement cars like the 3.4 liter Jaguar D-type, Ferrari 860 Monza, the 4.4 liter Maserati 450S and the 3.0 liter Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa would finish ahead of the German cars.

Many at Sebring in 1960 referred to the Porsche racers derisively as those “pygmy” cars and could hardly imagine them winning the first place trophy despite the fact that they took 3rd, 4th and 5th position in RSK’s in the 1959 race. Unfortunately, they missed the top two spots to a pair of 3-liter Ferrari 250 TRs that year.

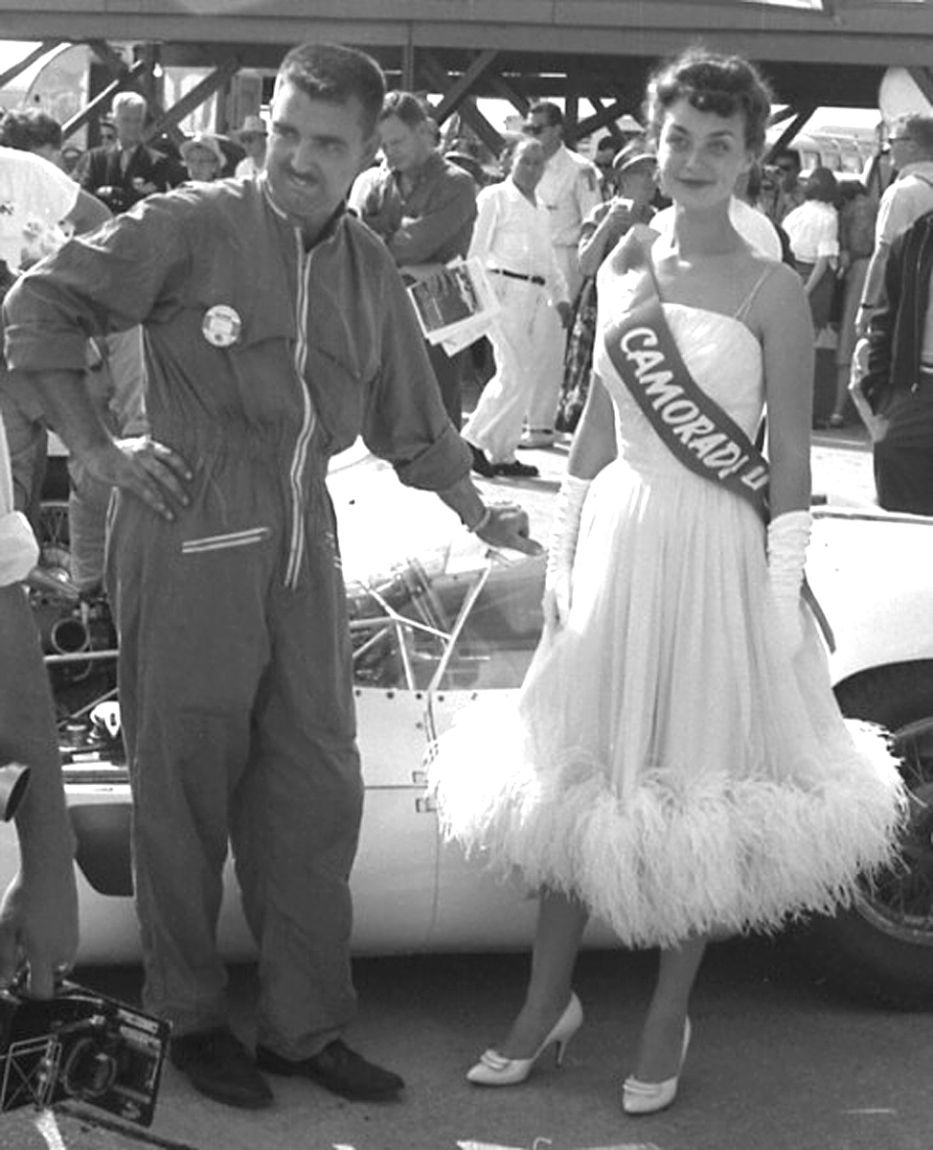

Speculation prior to the 1960 Sebring race held that British ace Stirling Moss had the odds-on chance of winning in his Camoradi USA 2.9 liter “Birdcage” Maserati Tipo 61. Wasn’t Moss the best in the world since the retirement of Fangio? Wasn’t Moss’s picture in just about every newspaper? The only thing that could jinx predictions of a potential Moss victory at Sebring in 1960 was Moss himself. He had a reputation for thrashing any car he drove and if the Tipo 61 could survive Moss then it would surely win.

Without doubt there were few Sebring 12-Hour races during this period in motorsports history that didn’t have some controversy attached to them and 1960 was no exception. Two problems arose. First, Sebring founder, race director and promoter Alec Ulmann had entered into an agreement with the American Oil Company (Amoco) that in exchange for sponsorship money Amoco would be the exclusive provider of race fuels at the Sebring race. Entrants would be prohibited from using any other fuels.

This created immediate problems for both Ferrari and Porsche. Ferrari had its own exclusive fuel arrangement with Shell Oil and Porsche had a similar agreement with British Petroleum (BP). Both Porsche and Ferrari notified Alec Ulmann that his agreement with Amoco was not acceptable and unless they could use their own race fuels they would not send a factory race team to Sebring.

Ulmann knew that a boycott by factory teams, especially Ferrari, would seriously damage the status and spectator drawing power of the race. Ulmann traveled to Modena, Italy to talk to Enzo Ferrari but they were not able to come to any kind of agreement. Later Ferrari as well as Porsche issued press releases announcing a factory boycott of the race.

According to an Associated Press (AP) wire story the rhubarb over the gasoline issue and then the announcement of a boycott by Ferrari and Porsche came as a surprise to Sebring promoter Alec Ulmann. He was surprised because Ferrari had raced under the same conditions the previous year (1959) and won the race. What Ferrari had done was sneak into the paddock a truck load of gasoline cans containing Shell gasoline. However each can had an Amoco sticker on the can. After the race when news of this was made public Sebring officials would counter that they had “…seized and impounded” those cans of gasoline and Ferrari was forced to run on the race sponsors product.

No sooner than the boycotts were announced to the automotive press both Ferrari and Porsche began to develop a way to get their cars to Sebring for the race. For Ferrari it was easy. All they had to do was ship their cars to Luigi Chinetti who at one time was the only Ferrari factory agent in the United States. Chinetti created the North American Racing Team (NART) and could function as a private entry in the race. Private entries were not bound by the arrangements between the factory and their fuel suppliers.

Wondering if he had a ride and a paycheck for Sebring in 1960 was two-time Sebring winner Phil Hill. The popular Californian had won the two previous years at Sebring as a Ferrari works driver but Enzo Ferrari notified him, team mate Wolfgang von Tripps of Germany and Englishman Cliff Allison they couldn’t drive at Sebring. Also absent from Sebring were the UK’s Tony Brooks and current world driving champion Jack Brabham of Australia.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Two

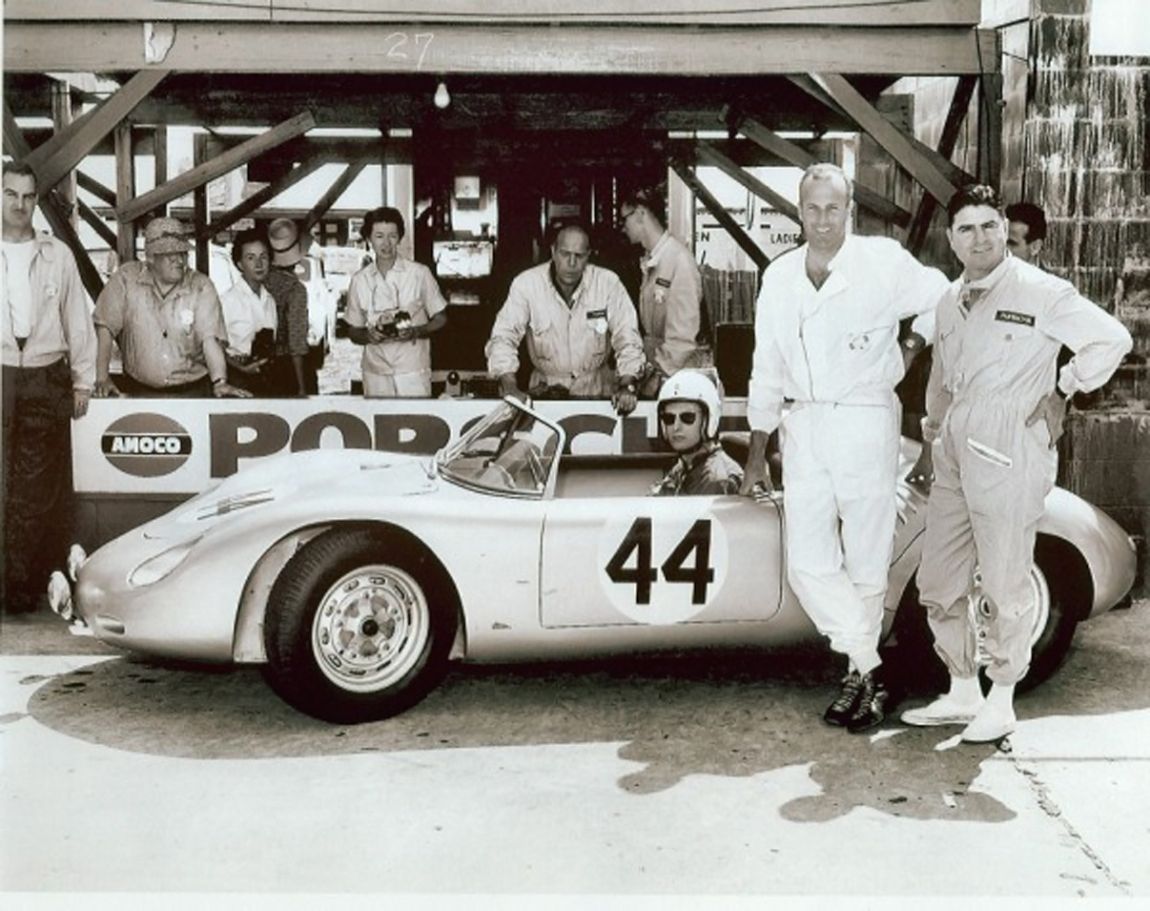

It was slightly more difficult for Porsche to have their best cars at Sebring in 1960 since they did not have a representative in North America similar to NART. Porsche came up with the idea to “lease” two of their race cars to Joakim “Jo” Bonnier who was from Switzerland and had been contracted to drive for Porsche at Sebring that year. With the boycott he was technically unemployed and with a little help from the factory he could act as a private entrant at Sebring in 1960. Porsche sent him two RS60 Spyders with all the newest modifications. All Bonnier had to do was arrange shipment to Florida.

As Bonnier was making those arrangements Porsche was surreptitiously arranging factory assistance for Bonnier’s efforts. A group of Porsche mechanics were allowed to go on “vacation” in March of 1960 and as luck would have it they chose to go to Florida and ended up “volunteering” to help Bonnier’s team. Another volunteer showing up in Florida was Baron Huschke von Hanstein who became Bonnier’s team manager for the race.

Same went for the factory drivers. Since they were not needed to drive factory cars at Sebring they were technically unemployed. Factory drivers Graham Hill and Hans Herrmann were encouraged to visit sunny Florida for a little R&R. As the story goes they just happened to “bump” into Jo Bonnier on their way to the beach one day and he invited them to drive for him at Sebring. This charade by Porsche was as thin as tissue paper but it passed the smell test and no punitive action was taken by British Petroleum. One last thing had to be arranged. While Bonnier would drive with Hill in one of the Porsches a co-driver had to be arranged for Herrmann’s Porsche. That wasn’t finalized until the last minute and many were surprised to see Oliver Gendebien on the starting grid on race day.

The other controversy facing the race organizers and entrants was last minute rules changes by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) concerning windshields and luggage compartments on the Grand-Touring or GT cars. This would be the first year that GT cars would be included in FIA Championship competition.

The competition committee for FIA had felt for some time that race constructors were modifying their cars by making windshields smaller and more aerodynamic and making luggage compartments smaller. They were getting further and further away from the street versions that appeared on showroom floors at dealerships. To address this issue the FIA ruled that all “open top” cars had to replace the cut down windshields with something close to factory specifications. Same went for luggage compartments.

Closed coupes like the six 4.7 liter Corvettes entered in the race had no problem complying with the new regulations. However, the Osca of Rees Makin needed so much work that when finished the new luggage compartment was so big that mechanics had to cut an opening fore and aft in the new compartment so the driver could see through it and hopefully any cars behind him. In the words of Ruth Sands Bentley, writing for Autosport, “…the car was rather reminiscent of a house trailer!”

The Osca of Denise McCluggage and Marianne Rollo had a problem similar to Rees Makin’s car. However, they had the genius of Alfred Momo on their side and he figured if you cut an opening into the cowl you could create a space large enough to qualify as a luggage compartment he hoped would pass the discerning eye of Sebring’s veteran Chief Scrutineer Monty Thomas, which it did. Momo’s modifications left the Osca looking more like the race car it was than an object of ridicule.

While not eventually a problem, but it could have been a disastrous one, the International Business Machine Company (IBM) wanted to provide the race with one of their new 305 RAMAC computers to do timing and scoring for the race. IBM executives felt that the Sebring race had achieved such national and international stature that it would be a good showcase for their equipment and flew one to Sebring in March following the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley, New York where it was used to score the events.

Accompanying the computer to Sebring was a cadre of 50 IBM techs and engineers to assemble and get the machine up and running. After landing at the Sebring airport the unit was transported to a hanger and kept under armed guard while utility crews wired the two pit stalls where it would reside during the race. Once that was done the unit was carefully transported to the track.

This was a great public relations coup for Alec Ulmann and Sebring but the track’s Chief of Timing and Scoring (T&S), Joe Lane, was highly skeptical of this “new fangled” technology. He was able to convince Ulmann to keep using the “human” T&S people as a backup in case of any troubles with the IBM equipment. As events would play out they were fortunate to do so.

You probably have more computing power in your smartphone today than was in the IBM 305 RAMAC in 1960. The one-million-dollar ($8-million today) behemoth weighed more than a ton and needed two pit stalls one of which had to be air-conditioned. The heat was generated by vacuum tubes and the fork lift used to remove the unit from the cargo plane that landed at Sebring had to do so gently lest the tubes were damaged. This behemoth had just 5 MB of storage capacity placed on fifty 24-inch diameter disks.

It took just two hours of racing for all the assurances of the IBM people to be proven false as the big machine failed to provide lap standings when needed. Thanks to Joe Lane and his stalwart T&S people they came to the rescue until the IBM engineers could figure out what the problem was. Seems that the old adage is true, “Garbage in, garbage out.” was the culprit. It took six hours to correct the problem and once done the machine began to produce good results.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Three

As usual Sebring fans began arriving early in the week before the 12-hour race on Saturday March 26. They went about their business setting up their favorite view spots and were enjoying the great weather for this year’s race. The previous year’s rains slowed all the race cars so no records were broken. The rains also made life in the spectator paddock miserable for all. To keep early arrivals entertained in 1960 Alec Ulmann had arranged for the first time a couple of preliminary races on Friday. One would be a 30 lap Formula Junior race run on the short (2.2 mile) course and the other a 4-hour endurance race for small GT cars on the full 5.2 mile course. Those cars had to have engines under 1,000 cc’s or no more than 61 cubic inches.

The Formula Junior event attracted some drivers of note including Jim Hall of Texas who won the event in an Elva DKW, as well as Ed Crawford driving a Stanguellini, Walt Hansgen, Augie Pabst, Pedro Rodriguez, Alessandro de Tomasso and Briggs Cunningham who drove a Cooper. Hall, who would become the face of Chaparral in a few years, averaged 88.007 mph for the 30 laps in his victory.

In the 4-hour endurance race for small GT cars on Friday Paul Richards won in a Fiat Abarth with Stirling Moss coming in second but first in class in his Austin-Healey Sprite. Richards ran 57 laps of the 5.2 mile course in the four hours for an average time of 73.968 to win the event. The only excitement in the race came when Bill Storey of Clearwater, Florida flipped his DB and was flown to a St. Petersburg hospital for a checkup. He returned to the track to watch the rest of the race from his pit, tenderly nursing bruises and abrasions.

Even before the green flag fell on the start of the 4-hour GT race on Friday the buzz going around the pits concerned the fact that that the hard charging driving style of Moss resulted in a blown engine on his Maserati during night practice on Thursday. The Camoradi team would eventually move Moss and co-driver Dan Gurney into the #23 “Birdcage” displacing drivers Jim Rathman and Col. George Koehne. This car was the same one that Moss drove to victory in the Cuban Grand Prix in February. Because of the Communist revolution in Cuba it would be the last grand prix race ever run in that country.

The rainy weather from the previous year was just a bad memory as a bright sun broke over the raceway on race day. Temperatures were expected to be high with some meteorologists predicting record heat for the race. While clear skies were welcome the heat was not and could take a punishing toll on cars, drivers and spectators alike. Track temperatures, which could reach 130 degrees Fahrenheit, had to be considered by each of the racing teams.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Four

Welcoming the heat at Sebring in 1960 were three young men who had driven down from the frozen confines of New York state to see their very first Sebring but not their last. For this story I was able to interview Dave Nicholas who along with his young friends were known as the BARC boys.

BARC – the Binghamton Automobile Racing Club was formed in 1958 by four teenagers from Binghamton, New York. Joe Tierno, Dave Zych, Steve Vail and Dave Nicholas all had a burning passion for sports cars and road racing. The BARC boys hooked up with Ed “Spankey” Smith and became his photographers. Sleeping in cars, sleezy hotels or flopping on the ground, they traveled the entire East Coast SCCA scene from Sebring to San Jovite.

The 1960 Sebring would be the BARC boys first visit to Florida and as Mr. Nicholas describes it:

Dave Zych and I drove down with Spankey Smith in his MG Magnette. There were very few 4-lane roads in those days and it was on this trip I saw my very first fatal accident. A Corvette blew by us going very fast around dusk on US 301 in southern Virginia or North Carolina. All of us in the MG were very jealous of the fellow in the Vette.

About 15 minutes later we came upon a police car with all its lights on and a real traffic slowdown. The Corvette that had passed us was in a thousand fiberglass pieces. It hit a dimly lit farm tractor that had pulled out on the road and the fast approaching sports car probably never saw him. The driver of the Corvette was killed instantly.

Yep, will never forget that this was the first Porsche win at Sebring. The sights and sounds of our very first Sebring are still with me today. I remember that Graham Hill was supposed to drive the #42 Porsche and practiced in it, but got switched to #43. You guessed it – Olivier Gendebien (we called him Jellybean, after all, who could pronounce Jahn-dib-ee-en) and Hans Hermann won in #42 and Hill and Jo Bonnier were a DNF. Holbert and Schechter probably would have won but had a tail light go out and had to stop for a bunch of laps to fix it.

We volunteered to crew for Denise McCluggage that year and the next and were able to get much needed passes due to our limited budget. We also raided local fruit groves for oranges and grapefruit which along with candy bars became our diet while we were there. Strangely enough we became extras for a movie being filmed at the track that year but Joe Tierno says I caused at least one retake because of my overacting.

Saw and heard those unbelievably beautiful Ferrari 59/60 Testa Rossa’s. Thick, dual, gray pipes running along the sides and curling back under the rear wheels and 4 great trumpets coming out the back, nothing comes close today. Chuck Daigh and Ginther led and then dropped out. And I was ready to fight Ricardo Rodriguez – same age as me and already racing. Remember in 1960 you had to be 21 in the USA to drive a race car. Not so in other countries and there was Ricardo Rodriguez, already a hero, driving Porsche Spyders, and his older brother Pedro in a factory Ferrari!! After that race we were definitely hooked and would return year after year as well as attending sports car events all along the East Coast.

Of the 65 cars that made the starting grid that day some looked very strange indeed due to the hasty modifications needed to comply with the new FIA regulations. A crowd estimated from a low of 15,000 to a high of 35,000 was smaller than what promoter Alec Ulmann had expected and when you consider that tickets were running at $5 a head it looked like Ulmann was going to see a big hit to his wallet. Later Ulmann would blame the boycott by Ferrari and Porsche for the lower turnout but the problem over fuel exclusivity would be resolved before the next 12-hour race. Regardless, the fans had come prepared to see some great racing, see who would win the gold plated Amoco trophy and see who would share in the $20,000 in prize money. Sebring would not disappoint as the birdcage Maseratis provided a lot of excitement for two-thirds of the race.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Five

As was the tradition at Sebring on race day Alec Ulmann conducted the driver’s meeting and then gave a brief welcome speech to all. This was followed by the command, “Drivers to your stations.” Drivers then walked to their spot opposite their car on the starting grid to await the signal for the Le Mans style start.

As they headed to their start positions the Corvette drivers broke off from the pack and headed for the first five positions on the grid followed by the Ferrari drivers. Cars were placed on the grid according to engine size and the 4.7-liter Corvettes were gridded ahead of everyone else since qualifying for a race was not used back then. Next came the 3-liter Ferraris and then the 3-liter Austin-Healey 3000’s. The fastest driver of them all, Stirling Moss, was 21st on the grid with his 2.9 liter Camoradi Maserati Tipo 61.

The tension in the pits began to build and almost became palpable as stewards began to clear spectators from the pit area and teams began to get their people behind the pit wall. Stewards were also trying to keep overeager press photographers from going out onto the course to get that “money shot” of the start of the race. For a steward this can onerous duty as race fans and press protest that they should be allowed closer to the track than is deemed safe. However, one steward took great delight in shepherding two very attractive females off the grid and into the paddock. Both young ladies were wearing bikini tops and tight shorts and a gaggle of photographers seemed more interested in them than the start of the race. Unlike today’s promo girls these young ladies did not have any advertising logos emblazoned on their attire so I can only assume they were promoting themselves.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Six

When the count reached one the green start flag dropped and the drivers sprinted to their cars hoping to be the first under the Amoco Bridge. That feat was accomplished by the Camoradi Corvette of Jim Jeffords with a trio of Ferraris in hot pursuit and before half way around the 5.2 mile track Pete Lovely would quickly take the lead in his Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa.

Stirling Moss had a bad start due to a hard starting Maserati engine and got away in 23rd position. By the end of the second lap Moss had blown by the pack and was second behind the Ferrari of Lovely. He would overtake Lovely on the third lap.

Lovely had been very lucky during the start because his Ferrari and the NART Ferrari 250 TR of Richie Ginther had bumped together tearing a valve stem off of the tire on Ginther’s car. This caused the tire to slowly deflate until he pitted for a tire change.

Making an unexpected pit stop on the third lap was the Maserati Tipo 61 of Maston Gregory and Carroll Shelby. As the car came to a stop by their pit, steaming water poured from the exhaust due to a blown head gasket. They became the second car to retire preceded only by the Porsche 718 RSK of Ernie Erickson and Don Sesslar that made only one lap and had to retire due to a broken timing gear.

Nineteen minutes after the start and on the fifth lap of the race a tragic accident occurred at the hairpin turn. The Lotus Elite of Jim Hughes and Sam Weiss was coming into the turn when the Lotus lost its brakes and headed for the escape road at a high rate of speed. Unfortunately right in the middle of the escape road was 23-year-old Tampa Tribune photographer George Thompson who had his camera set up on a tripod. Driver Hughes tried to avoid hitting Thompson but only succeeded in rolling his car, striking Thompson and causing the death of both.

Such an accident today would have brought out the red flag to stop the race. Back then the race continued as corner workers cleaned up the debris and ambulances transported the fallen to the track hospital. While all this was going on Stirling Moss gained the lead and was now 12 seconds ahead of the Lovely Ferrari. In third place was the 2-liter NART Ferrari of Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez. The brother team of Ricardo, 18, and Pedro, 20, were in the same car for the first time at Sebring. Ricardo shared the Index of Performance trophy in 1959 driving an Osca and Pedro came in second behind Stirling Moss at Cuba in February of 1960.

At the end of the first hour (11 am) the standings were as follows: The Stirling Moss, Dan Gurney Maserati T61 was in first followed by the T61 of Walt Hansgen and Ed Crawford. Next came Richie Ginther and Chuck Daigh in third with a Ferrari 250 TR/60. Next was the Ferrari 250 TR/59 of Jack Nethercutt and Pete Lovely and fifth was the NART Ferrari Dino 196S of Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez. Already five cars had officially retired with another three in the pits with ongoing repairs.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Seven

On lap 21 Ginther and Daigh set a new record average of 94.479 mph. This broke the record of 93.6 mph set by Stirling Moss in an Aston-Martin in 1959. Five laps later the Cooper Monaco Maserati of Hap Sharp and Jim Hall swallowed a piston just after turn one and the driver parked the car and began the trek back to the pits. One lap after that the Briggs Cunningham, John Fitch Corvette suffered a rear hub failure going into the Webster turns. Just as driver Fitch was going into the hard turns of Webster a wheel snapped off the Corvette causing the car to roll over. Witnesses said that Fitch was out of the car before it finally came to rest, chasing the errant wheel that was rolling towards the track surface and endangering the other drivers. Fortunately Fitch was not injured but he knew that media legend Walter Cronkite was broadcasting the race nationally on the radio from the pits. He quickly returned to the pits and tried to find a phone to call his wife in Connecticut and tell her he was okay.

At the start of the lunch hour the Moss/Gurney Maserati continued to lead with the Ginther/Daigh Ferrari second, the Hansgen/Crawford Maserati third, the Rodriguez brother’s Ferrari fourth and then three of the Porsches. This would be the hottest time of the day and pit stops and driver changes became more frequent as the heat took its toll on man and machine alike. Even the pit crews were suffering in the heat as some of the Germanic and previously very pale crews, began to show the effects of too much sun. Wives and girlfriends were being dispatched to vendors in the paddock or into the town of Sebring to find sun-tan lotion. Unfortunately in those day the stuff had little or no sunblock. No doubt when they got back to a very cold Europe they would have to explain their red and pealing sun burns.

The drivers and crews were not the only ones suffering from the heat as the first aid station in the spectator infield began to experience brisk business. Manned by volunteer Red Cross and Civil Defense workers they treated over 90 race fans for a variety of ailments including sun burn, cuts, bruises, excessive alcohol consumption, fainting brought on by the heat and minor burns from camp fires and cooking fires. The worst case was a race fan who took a header off the top of one of one of the grand stands and had to be transported to a hospital for observation.

The high track temperatures increased tire wear and pit stops usually included a complete set of new tires. Tire vendors in the paddock were hard pressed to keep the teams supplied. Out on the track bits of black tire rubber were being thrown onto the track surface with noticeable deposits on the outside of the Hairpin and Webster turns. Any car going wide in those turns might lose traction and end up in a sand bank. The better prepared driver usually carried a shovel in the trunk or behind the driver’s seat in case one needed to dig one’s self out.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Eight

On lap 34 the McCluggage/Rollo Osca retired with bearing failure. Not long after (lap 54) an Austin-Healey driven by John Colgate and Fred Spross flipped at the end of the front straight followed soon after by the flip of the Lotus Elite of Frank Bott. Ever the stalwart competitor Bott proceeded to right his overturned car and then drove it very slowly back to the pits. Entering pit road many were amazed to see a car minus the driver’s side door, rear window and front windshield. His pit crew took one look at the car and threw in the towel. The car was retired after 57 laps. At that point Moss was still in the lead but his lap average had slowed slightly to 90.852 mph. If Moss and Gurney had maintained that average they would have beaten the record set by the Phil Hill, Peter Collins Ferrari in 1958.

In addition to providing tires, gas, and oil for their cars some of the pit crews were tasked with cutting holes in the larger than normal, but FIA approved, wind screens. It seems that the large Perspex surface areas were quickly covered by Florida bug guts, oil and grit from the track to the point where they were almost opaque. Viewing ports had to be cut so the drivers could see where they were going on the track. Despite some concern expressed by pit stewards nothing was done to stop this activity. As far as the crews were concerned it was a safety issue.

Between one and three in the afternoon the Moss/Gurney car held the lead but was beginning to slow slightly. They were now averaging 90.852 mph and no doubt the afternoon heat was taking its toll on all concerned. The 3-pm standings included twelve cars that had been officially retired with the usual handful in the pits for repairs for a variety of ailments. Some would return to the track and others not.

Of those going behind pit wall were two Corvettes, the 250 G.T. Ferrari of Carlo Abate and Gianni Balzarini, a Sprite, a Maserati, a Morgan, an MGA, two Porsches, an Alfa, Lotus Elite and an Osca. Most of these retirements were related to engine problems but four cars retired due to accidents. One of those accidents resulted in the loss of two lives and it was obvious that the notoriously rough Sebring airport course was living up to its reputation. As the standing were eventually updated by the now functioning IBM computer five more cars were added to the withdrawal list. They included an AC Bristol, a Bandini-Fiat, an Austin-Healey 3000, another Alfa and a Lotus.

Being worked on in the pits at this hour was the NART Ferrari Dino of the Rodriguez brothers. The mechanics were furiously trying to replace a broken universal joint which took 30 minutes. Prior to that problem the brothers were running very respectable 3 min., 20 sec. laps.

Just down from the Rodriguez brothers pit was the Jo Bonnier, Graham Hill pit and the mechanics were craning their necks to see what has happened to their long overdue car. At that moment Hill’s Porsche 718 RS60 was parked near the Webster turns with a rod through the engine block. They were officially withdrawn after 87 laps.

Coasting to a stop in the pits was the second-place Daigh/Ginther Ferrari. It was obvious from the steam pouring from under the engine bay hood that an overheating problem had to be addressed. While doing just that the Ferrari mechanics gave the car four new tires and tended to several other minor repairs.

At 4:05 pm the infamous hairpin turn claimed another victim in the form of the third place Crawford/Hansgen Maserati Tipo. The car went a little too wide in the turn and got well and truly stuck in the sandbank at that turn. Driver Ed Crawford didn’t have a shovel in the car and proceeded to dig himself out by hand. This was very dangerous work because other cars were passing by just a few feet from the digging driver who at times could be seen on his hands and knees with his butt high in the air. It would be almost two hours before the car would return to the track.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Nine

At the half-way point in the race Moss and Gurney were still leading and averaging 3 mph faster per lap than the second place Daigh/Ginther Ferrari. Hans Herrmann and Oliver Gendebien were now in third with their Porsche RS60 and the Nethercutt/Lovely Ferrari was in fourth spot a full nine laps behind the leader.

The Crawford/Hansgen Maserati was now free of its sand trap and on the way back to the pits but at a much reduced pace. Hitting that sand bank damaged the front wheels and it would take the Camoradi mechanics 45 minutes to get the car going again. In this effort Briggs Cunningham was enlisted to vacuum sand from the damaged car.

After completing 123 laps the Daigh/Ginther Ferrari was retired at 5:23 pm. The car had been smoking badly for some time and when Daigh brought it into the pits for the last time the left side of the car was covered in oil and so was Daigh. It was a sad end to one of the better performances of the day.

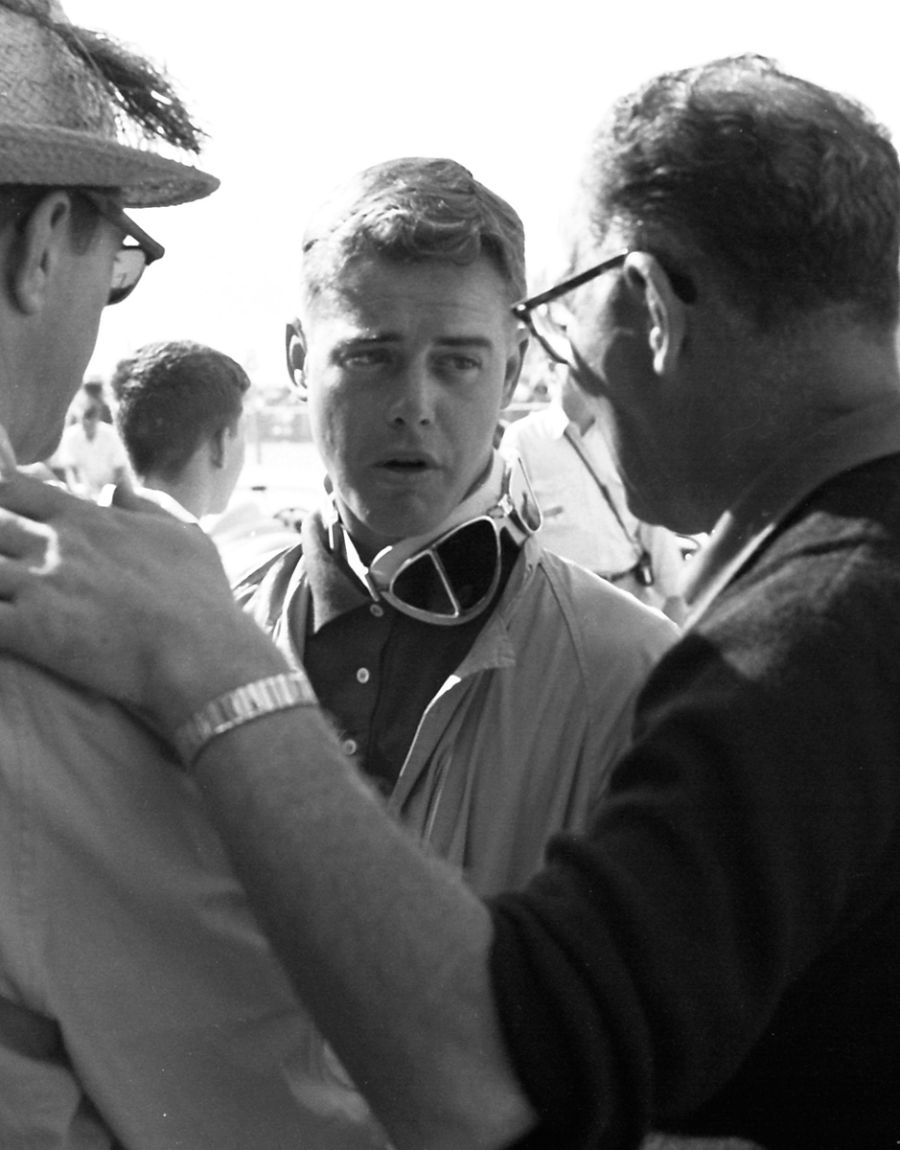

Just minutes later Dan Gurney was in the pits for a scheduled pit stop and driver change for the leader. After talking briefly to Moss he went over to talk to some journalists. They asked why the pit stop was taking so long. Gurney indicated that the mechanics were missing a special tool that made changing the brake pads easier and quicker. Gurney also said, …” that there was a noise coming from the rear end.” He added, “I’d be surprised if he (Moss) would make a lap.”

Despite the long pit stop the car returned to the track still in the lead and being piloted by Moss. Not long after the car could be seen coming down the east-west runway rather slowly and then entering pit road. After 136 laps the car was retired at 6:05 pm with rear end trouble. The Porsche of Hans Herrmann and Oliver Gendebien would soon take the lead.

As he exited the car for the last time Moss grabbed the huge pad of foam rubber that allowed the diminutive Moss to see adequately in the low slung Maserati. After entering his pit he was surrounded by reporters. While Gurney was in the car when the trouble struck Moss was quick to deflect any criticism of Gurney’s driving. He told the reporters that it was not Gurney’s fault. “It’s just my bug,” he said ruefully, referring to the bad luck that often dogged him at Sebring.

Just a few feet from Moss and the reporters the flag was being displayed to all cars to turn on their lights as the sun began to set. Sunsets at Sebring can be quit spectacular in March as the sun back lights the cars coming down the front straight with their lights on. However, night time can be particularly scary because large portions of the track are without any illumination and in pitch black darkness. On several occasions, in other 12-hour races, cars were reported to have gotten lost on the huge expanse of concrete runways and taxiways. Some drivers who were new to Sebring were told prior to the start that at night you should try to follow a driver you know who has raced at Sebring before. With darkness the pace slowed to a lap average of 85.899 mph.

It was not only dark on the remote parts of the course but in the pit area the lighting was so minimal that pit crews had difficulty signaling their drivers with signal boards. It took two to three people to do so with one holding the signal board and one or two with flashlights to illuminate the board. One enterprising crew had built a neon lighted sign with which they were able to message their driver. Many of the other crews looked on with envy.

With 3-1/2 hours left in the race the Herrmann/Gendebien Porsche was firmly in the lead with the Holbert/Schechter/Fowler Brumos Porsche in second. There was a scary moment at this time for the Brumos crew as Holbert brought the car in with a bad leak in the cam covered gaskets. A 19-minute pit stop fixed that problem and they were back in the race. Moving up to third was the private entry Maserati of David Causey and Luke W. Stear. The NART Ferrari Dino of the Rodriguez brothers was forced to retire due to clutch troubles while younger brother Ricardo was at the wheel. For over eight hours they had driven a tremendous race in their 2-liter Ferrari.

1960 12 Hours of Sebring – Race Profile Page Ten

Of the eight cars brought to Sebring by Camoradi USA only two were still running. At the moment they had the Corvette of Jim Jeffords, Fred Gamble and Bill Wuesthoff still in the race but far back. However, the Porsche of Joe Sheppard and Dick Dungan was running 10th overall and leading in their class. The Sheppard/Dungan car was the last best hope for the Camoradi effort at Sebring and the entire crew of mechanics and support personnel were concentrating on getting that car to the finish line.

The monumental effort by Ed Crawford in digging his Maserati out of the sand bank in the hairpin turn was for naught as the car was withdrawn shortly after 8 pm with a broken pinion gear. With 10 hours of racing gone the standings were Herrmann/Gendebien Porsche first, Holbert/Schechter/Fowler Porsche second and now moving into third was the Ferrari 250 GT of George Reed and Alan Connell. Those standings would change little from now to the end of the race as drivers became reluctant to take any chances in the dark. Many just hoped to finish the toughest sports car race in North America which for some could be the accomplishment of their racing career.

Throwing caution to the winds were Ferrari drivers Pete Lovely and Jack Nethercutt. Driving a Ferrari 250TR/59 they were making a run for the podium and turning 3 min., 32 second laps. During this run they would pass four of the six cars ahead of them to finish in third spot behind the two leading Porsches. Seven Ferraris would finish in the top ten at Sebring in 1960.

While that drama played out on the track there was plenty to see in the pits. The Jim Jeffords, William Wuesthoff Corvette caught fire in the pits as mechanics were working on the car. The fire was quickly extinguished and they were able to finish the race in 26th position. The highest finishing Corvette would be driven by Jim Hall’s brother, Chuck. Co-driving with Bill Fritts the car would come in 16th overall. Following closely across the finish line on the same lap but 17th overall was the Lola Mk. 1 Climax of Charles Vögele and Peter Ashdown. They had an OMG moment in the race when the hood flew off the car but instead of stopping to retrieve it Vögele drove the car back to the pits. There he found out that there was no spare and stewards would not let him continue without it. So, back he went, on foot, to where the hood was lost only to find out that some race fans had appropriated it for a souvenir. Fortunately those folks listened to the pleadings of Vögele and returned the hood.

Late in the race the AC Bristol of Mike Rothschild and Bob Grossman was experiencing a total loss of oil pressure due to a severe leak. Mechanics would add seven quarts of oil to the engine only to see the car back after two laps with no oil in the sump and oil dripping everywhere on the concrete in front of their pit. While the mechanics added more oil to the engine Rothschild slipped on a patch and sprained his ankle. While in some pain he decided to finish the race and reentered the car only to have his oil soaked shoe slip on the clutch pedal when he tried to start the car thus stalling it in the pits. The battery was stone cold dead and if not for the use of a booster battery from another pit the car would have finished the race there. As it was they managed to finish in 21st place and third in class.

With 45 minutes left in the race Gendebien was in for a quick 20-second pit stop just for enough fuel to finish the race. He was preceded by the Camoradi Porsche 356B of Joe Sheppard and Dick Dungan five minutes earlier. Like Gendebien he got just enough fuel to finish. Sheppard also got a swig of water to get him to the checkered flag and ninth overall.

The checkered flag dropped at 10 pm with the Porsche RS60 of Hans Hermann and Oliver Gendebien taking the overall win with 196 laps completed at an average speed of 84.927 mph. They were followed by the Holbert/Schechter/Fowler Porsche with 187 laps completed and the Lovely/ Nethercutt Ferrari third with 186 laps. Five more Ferraris would follow the two leading Porsches, then another Porsche, and another Ferrari to round out the top ten. For their efforts the winning drivers would pocket $3,000 or $23,703.75 in today’s dollars.

In the winner’s circle there was the usual crush of people cheering and flashbulbs going off. Reporters jostled each other for a chance to get a quote from the winning drivers who were holding the huge 100th anniversary gold plated Amoco trophy. Alec Ulmann’s wife, Mary, placed wreaths of kumquats around the necks of the winners. This was not always appreciated because sometimes those kumquats had bugs in them as experienced by Jean Behra in 1957.

The boycott by factory teams, the absence of some name drivers and the lower than expected turn out of race fans resulted in some critical reviews in newspapers following the race. Those poor reviews were repeated several months later when automotive magazines went to press. Many felt that if it hadn’t been for the drawing power of one driver, Stirling Moss, this might have been the last Sebring. Rumors about the “last Sebring” actually got their start in 1960 and continued for years to come.

Some journalists were highly critical of the Sebring promoters as a result of the death of a driver and a press photographer in 1960. A small number questioned the casual approach by Sebring officials toward track and spectator safety and predictions were made that more tragedy was to follow unless safety improvements were made. Follow it did in 1966 when a driver and four spectators were killed. Among the dead were a mother of three and two children.

Despite those poor reviews the race was significant because it was the first win by Porsche in a major international endurance race. It was also the first time a rear-engine car had captured the overall trophy at Sebring and the Stuttgart-based manufacturer would go on to nearly win the 1960 Manufacturers Championship with their little RS 60’s. Porsche wouldn’t win at Sebring again until 1968 but their cars would dominate international endurance racing in decades of ’70s and ’80s.

The 1960 Sebring race would be the last year that Amoco would be the major sponsor of the Sebring race. Due to the turmoil surrounding the boycott of Ferrari and Porsche the FIA ruled that Sebring could no longer mandate the use of Amoco gasoline for all entrants in an international race. When Ulmann protested that the FIA allowed the same exclusivity at the 24-Hours of Le Mans the response from the FIA was essentially, “That’s different!” So, the American Oil Company reluctantly withdrew sponsorship of the race.

For Further Reading:

Bentley, Ruth Sands. “Porsche ‘One-Two’ at Sebring.” Autosport, 1 April 1960.

Breslauer, Ken. Sebring: The Official History of America’s Great Sports Car Race, David Bull Publishing 1995.

The Tampa Tribune, 24-27 March 1960

Ulmann, Alec. The Sebring Story. Chilton, 1969

“A Win Over Mighty Moss” by Alfred Wright, Sports Illustrated Magazine, April 4, 1960

[Source: Louis Galanos]

1960 Winter Olympics were in Squaw Valley, Ca

Thanks for that information Bob.

Most excellent article, Brought back many memories.

Great article again Lou, nice job. Good memories….Jim Beebe

Thank you Lou — this is yet another of your wonderful photo compilations integrated with excellent commentary that brings to life a classic race. I was delighted to see my father’s Alfa in two of the photos. As noted, he co-drove it at Sebring with Bill Milliken. That was the last race for both of those great friends. Note the New York State license plate on the Alfa — the car had just been delivered and was driven to the race. My brother, J.C. Argetsinger, drove the Alfa back to Watkins Glen after the race with absolutely no brakes. J.C. is now the president of the International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC) at Watkins Glen. Thanks again Lou. Michael Argetsinger

Another excellent article on Sebring by Louis Galanos! I’ve enjoyed reading all your articles on the 12 Hours. The only thing that stood out to me was the Amoco anniversary date…I believe it was the 50th instead of 100th. Thanks again for keeping the memory of Sebring alive!

Thanks, great shots and memories. I had not seen (or long forgotten?) the photo of my father in the Arnolt-Bristol. The year before he raced a 250 TR.

Another outstanding article by Mr. Galanos! – I enjoy going to vintage races, but it’s so much seeing original photos like these – set in their own times. What a treasure.

I especially enjoyed seeing the Arnolt Bristol being raced – another great design by Scaglione that has stood the test of time.

& the IBM Computer hard drive that looked like a giant stack of pancakes… What a hoot!

When asked, a few months ago, if I had been at Sebring in 1960, I replied “yes, I was there;; but except for remembering a couple of very reliable winning Porsche’s and some wicked sounding unreliable Maserati “Birdcage” race cars, I don’t remember anything”. Thanks Lou, for reminding me, in detail , that there was A LOT MORE to remember! Mario

A great article on historical racing at Sebring, with many fine photographs. Those early Porsches were clean, well engineered machines that always gave the more powerful and exotic cars fits, and in this instance, beat ’em. Silver has always been my favorite color. Thanks, Lou

Thanks Lou, great job. With your help I now remember the race but the behind the scenes conniving by the “big boys” reminds me of the politics of auto racing. Guido

Simply marvelous!!! What a great start to my day (even if I just put myself 1/2 an hour behind schedule).

In 1960, as a 12 year old newly addicted aficionado , I could only watch the “boys”, including our neighbor John Fitch, driving off from our village of Lime Rock for Sebring with wistful longing.

Lou, such a fine narrative… and to you old BARC boys??? Every-time I rummage through your archives of images I recall and refresh another part of my ancient memories…

Many, many thanks.

dlm

I remember those races with such fond excitement. My family lived in Sebring from 1954 to 1962, and from 1960 onward, I never missed a race until I went off to Chapel Hill in 1967. Those were great days! I worked, as a 14-year old, as Mr. Ullman’s gofer, for the 1962 race. He was a very focused gentleman, demanding but not harsh. He kept a Benz 300SL roadster in front of the Jaguar tower as his personal vehicle, and when something happened out on the course that concerned him, he just jumped into it, burning rubber down the pit lane. What excitement!

Always nice to hear from someone who was actually there during that golden age of racing.

How lucky we are to have Louis Galanos & Dave Nicholas alive to re-live this race (and other races) personally and share the grit and reality with us. Things can get so distorted today. As I read this I felt like I was there. I just can’t say enough. Except for bugs in the kumquats?

Louis on my gosh I have now been to Sebring in 1960. What an excellent commentary and wonderful array of historic photos. We fortunately see these wonderful cars on the lawn at Pebble Beach or on a track in the historic races but to hear about the drama behind the scenes and learn how mechanical failures were so common is very enlightening. We are reaching a new summit of interest in this era and thankfully many of the cars and drivers are still around for the next generation of race fans. Thanks for your excellent work.

Your Flickr Buddy

Wayne Craig

Thanks again Lou, for rekindling those dim memories. I examined each one of the pictures closely as 1960 was my second Sebring (only as a spectator-I was a senior in high school), hoping I might be lurking somewhere in the background. Alas, no luck, but I only missed a couple in the next 40 years, many working for the SCCA. Great story!

Thank you so much for your well-written and informative article and photos. You mentioned the 860 Monzas at

Sebring. There were three cars {S/Ns 0602M, 0604M, and 0606M}. These were the only Tipo 860 Monzas.

S/N 0604 won the race, driven by Fangio/Castellotti. I owned and raced 0604M from 1959-1967. This was an

experience I will never forget. I was not fast, but no one enjoyed their car more. Back then, I did everything

myself. I built a trailer {with springs and brakes, unheard of at the time}, converted my truck from manual to automatic transmission for towing, drove the truck, drove the car, loaded/unloaded car, did all pre- and post-

race chores, all mechanical and paint work, etc etc etc. The car was a joy, and still is.

Times are different now. I paid $5000 for the car and sold it for $3600; I think the last valuation I saw on it

was $6M+. At the time, my salary was about $10,000/year; my financing is a story all by itself. I was very

lucky to have lived at the time when an ordinary guy could do the things I did. Tempus fugit, doesn’t it?

Thanks again for what you do.

Charlie Cravens

Wonderful having you comment about my story and sharing your remembrances of past racing days when a car owner/driver could do it all.

Reading this article while viewing the photos, I felt I was there. Great work….

Dear Lou,

When I awoke this morning I was reminiscing about matters that are important in life and my favorite memories of all times. I concluded that without a doubt my favorite memories are of Watkins Glen in 1952 and Sebring during the golden years of 1959-1962. Then two hours later I read your fabulous article. The irony is overwhelming.

It was as if someone pushed the replay button in my brain as I continued to read. The photos provided by Dave Nicholas and his fabulous website, http://www.barcboys.com are stunning but so very familiar.

In 1958 Nicholas, Dave Zych, Steve Vail and I started the Binghamton Automobile Racing Club (BARC). We were fortunate to grow up in a time and place that made all of these memories possible. For decades after our many trips to Sebring, we saw many of these images over and over again. Thankfully, Spankey Smith, Dave Zych, Steve Vail, John Kelley and Nicholas were good stewards of these images. We should all be grateful that they can now easily be shared with others. I know that Nicholas has had many other contributors to his website and their efforts cannot be underestimated.

My personal favorites however will always be images we saw hanging in the homes of BARC members, collected in scrapbooks or shown as slide shows. I remember one occasion where Sebring slides were shown on a screen while Peter Ustinov’s Grand Prix of Gibraltar played in the background. Those were great days.

One memory that popped into my head is the “Amoco Porsche” sign indicating who was assigned to that pit box. The pit box signs were sturdy but nonetheless temporary. It was customary that those signs were removed by race fans but such action was not considered to be vandalism, at least it wasn’t in 1960. The BARC boys were a little timid at first but we did acquire a sign. The last I knew it was in Nicholas’ home in Binghamton.

Lou, in closing I would like to say your research is phenomenal. Every little tidbit adds to the story and helps us enjoy that lost period of racing even more.

Thank you very much.

Joe Tierno

Great to read about classic races. I was a teenager in Englewood, Ohio and was able to listen to the race on a big console radio. What fun? One slight correction – Mr. Gendebien’s first name was Olivier not Oliver. Thanks for the story.

Jim S.

Great article. I have a 2008 Porsche RS 60 Boxster S & would love to have a hard copy?

Great article! Brought back many memories. I was at the race with Art Smith. We drove from Buffalo in a Karmann Giha in 30 hours. Our Ecurie Pip! wound up owning 5 of the cars from that race, Three MG twin cams and two Austin Healeys . I had the Practice Twin Cam, raced it for a year and sold it to Bob Moran. It later sunk on a boat and is at the bottom of the Carribean near Cuba. Many years later I bought the Practice Austin Healey from Dick Ecklund. I ran the Healey in vintage racing from 1992 to 2006. It is now back in the UK. Cheers, Bob Deull

Thanks as always, Lou, for helping keep the history of the sport alive.

Charles Voegele, owner and driver of the Lola Mk1 he shared with Peter Ashdown, was well known to my dad, through racing and because he (Voegele) bought all the stationery and computer forms for his new mail-order business in Switzerland from him. Charles Voegele was first in bringing a Lotus Elite, in wjhich I had a ride as an 18 year old, to the continent, much to the chagrin of the Giulietta SV drivers. The Lola came after that, and Voegele helped finance Eric Broadley’s fledgling company for some time. Spark made a nice model of that Lola and it sits on my bookshelf. Both his sons are in historic racing, Carlo, amongst other cars, owns the unique 330 GTO which he ran some years ago at Laguna Seca.

Most likely the best recount of a race weekend I’ve ever experienced! Much less 44 years ago! Remarkable read!

Many thanks to you and all the others for your kind comments. As a retired history teacher these vintage racing stories have been a labor of love for me. Fortunately for me the kind folks at Sports Car Digest have been nice enough to publish my work and for that I am grateful.

Another terrific account that makes history felt in a way few writers accomplish. The inevitable connections to the former driver’s that we had the privilege of knowing in the years to come, only increases the respect for them as well as the history of Sebring itself. Your writing Louis reminds me a lot of what I respected about Walter Cronkite. Concise, accurate and entertaining mind attendance of a race I wasn’t even at. Thanks again to you and the BARC boys

Burt

I really enjoy this article and the photographs. Thank you.

Tom Bucher

Insightful and awesome pictures!!

Nice article. Love the pictures and all the behind the scene information. Great job!

Jim

Hi Mr. Galanos. Am hoping you’ll see this. You posted a picture in your Flickr portfolio that captured my Uncle Mike driving the #34 Corvette on the grid @ the 1973 24 hrs of Daytona and I’d like to see if I can get him a copy of it (as a matter of fact, today Oct 2nd is his birthday). The photo is this one: https://www.flickr.com/photos/smuckatelli/2876354257/sizes/z/

Is it possible to buy a copy of that photograph? Thank you.

Patrick Murray

Patrick: Email me at [email protected] and I will do what I can for you.

I will, thank you very much.

Just wanted to publicly thank Lou for his kindness and time in my quest to get my Uncle that picture of his car on the Pace Lap during the ’73 Daytona 24 Hours… Thank you Lou!!

Hello

I bought 10 years ago an AC Bristol BEX 1147 in Japan and I discovered a few years later that that AC was the one of Bob Grossman that race at Sebring 1960 .

I still have the car that is fantastic and I am looking for any documents or period pictures

Thank you to everybody that could help me .

Regards

Laurent

Hi Laurent

As you may have seen on the AC owners club forum I used to own BEX ii47 from about 1974-1978.At that time I knew it had Grossman history but was told it was just bought originally from his dealership I have lots of pictures from when I owned it.

Hello Mike

Sorry for my English but I am French !

I was very pleased this morning when I saw your email !

Yes I have read that you were the owner of BEX 1147 in the ACOC . The must funny things about BEX1147 is that I bought the car in Japan around 10 years ago and I didn’t know anything about the history of the car . When I received the car because I bought her without seeing the AC , I noticed there were holes in the body , I thought there was a rolling bar and also an oil cooler and an oil temperature gauge, but nothing more . The engine was badly running , they have mixed the wires of the ignition ! And for two years nothing . And when I wanted to register BEX 1147 in France , on the Japanese title the year was 1962 and there was no more AC Ace in 1962 , so seems me very strange so I contacted the ACOC and If I relay well Mr CRAWFORD gave me the history of the AC , works car, Sebring 1960 with Bob Grossman : You can imagine how lucky and happy I was .

So BEX 1147 is now in France with my 1928 W.O Bentley that I race and my 1955 Cooper Jaguar HOT 95 !

I give you my email : [email protected] and it will be nice if you can send me some pictures . I have an antique business in San Francisco , The Butler and The Chef but I don’t go there very often , business is too quite !

Where are you located in the U.S ?

Regards

Laurent

Four years later I answer–I am in New York. Do You still own BEX1147?

Hello Louis,

I own a 1960 Corvette vin #2, built in August of 1959.

Has Aluminum heads and fuel injection, further it is a cz block of which only 1 was made.

Supposedly crower never made alum heads but mine are stamped and dated 6/24/59.

any further info would be great!

Thanks,

Bill Fortune

Wow, great article with outstanding photos, thanks for sharing those amazing Sebring memories.

I was at the race as a “gofer” with the Coconut Grove contingent of N.A.R.T.,I got on with Cunningham Motors in Coconut Grove in 1959,just before the Formula One race at Sebring.We brought the Tec Mec re-worked Maserati 250 Formula One car up for the race,but Mr D’Orey had an engine failure in practice. In 1960, N.A.R.T. had a raucous house party on a lake in town,and went to Tech inspection with a slight hangover.Phil Hill was my personal favorite,an absolutely great,fun guy.Our cars prevailed.

Nice overview of the pre-race story… but how about the story of the race? That could have a narrative too. I was not even born back then, but I enjoy all these stories from when racing was so amazing! Thank you for the story, I didn’t know about the fuel story. It was mostly about Ferrari. How about Porsche, how did they do to enter the race?

I was there. A friend of mine and I drove his 57 MGA non-stop from Virginia. The Lotus Elite accident with the photographer happened right in front of us. I watched it happen. The photographer kept jumping out in the escape road to get photos of cars coming down the straight away. The Track Monitors kept chasing him out. As soon as they left, he jumped out there again. I don’t remember his tripod but I saw him get hit. The Lotus lost his brakes and took the escape road. The photographer was right in the middle of the road. By the time it registered with him that the Lotus was not turning but was taking the escape road, it was too late. He dropped his camera away from his face and BAM! He was hit. The Lotus slid sideways, hit the photographer with the driver’s door, and flipped. They were both killed. Sad. Especially for the driver. That was the first time I ever saw someone get killed right in front of me. I’ve thought about it many times.

Stirling Moss was clearly the fastest driver and not by a little. He was remarkably faster. If he hadn’t broken his Birdcage Maserati, he would have easily won the race … by a bunch. He was flogging his ride really hard. It was impressive to watch.

If the Maserati had been half as good as its driver, it would’ve been some kind of record, I’m sure. Unfortunately, the Birdcage Maserati was really fast but was also very fragile. Too bad. Of course, the well engineered, reliable Porsche Spyders won handily after Moss was out. It was a memorable race.

I remember this black gullwing Mercedes 300SL with red leather interior that was for sale at the track. I wanted it really bad but couldn’t afford it. It was like three thousand dollars and I was 18 years old. That car today is worth a lot of money. It would’ve been a good investment.