Every legend has its debut day: this was the case of the Porsche 911, which, in 1965, had its baptism of fire in the feared Monte-Carlo Rally. This was the first chapter in the victorious path of the 911, an adventure marked by great challenges and obstacles, crossing Europe from North to South. Now, readers can check this incredible tale, of the first milestone of a mythical car.

A REVOLUTIONARY CONCEPT

The origins of the Porsche 911 can be traced to the need to find a spiritual successor to the 356 model, which had been manufactured by the Stuttgart automaker since 1948. It was clear to the Porsche design team that the 356 was already at the end of its evolutionary cycle, and it was necessary to start developing a replacement worthy of the German manufacturer’s badge.

In the mid-50s, the first drawings of what would eventually become the mythical 911 began to appear – and, in 1961, the first prototype of the new car, known simply as the “Typ 754 T7”, was built.

The project’s core team revolved around some key personas inside Porsche: Ferry and “Butzi” Porsche, son and grandson, respectively, of Porsche’s creator, Ferdinand. Engineers, mechanics and designers Klaus von Rücker, Leopold Jäntschke, Hans Mezger and Ferdinand Piëch; in addition to Erwin Komenda, the leader of the Porsche car body construction department.

The squadron bent over the drawing board over the next few years, continuing to refine the “754 T7” project; till 1963, when at the Frankfurt International Motor Show, as a result of years of trial, refinement and error, the new car, now rebranded as the Porsche 901, was officially revealed to the world.

Upon its unveiling, the 901 caused a great sensation: from a design point of view, the car preserved some features of the 356 “Karmann hardtop”, which had a closed roof and a teardrop body shape. Even though in the general context there was this similarity, it was obvious that the 901 represented a step forward in the concepts of car design. The vehicle had much more aggressive and insinuating lines than those of the 356, without losing the charm of Porsche cars.

The new 911 body also had other advantages compared to the previous Porsche models, especially in terms of internal space. The 901 was 20 centimeters longer and 10 centimeters wider than the 356A (the standard 356 model), which allowed greater comfort, accommodating up to three passengers plus the driver.

However, the great strengths of the initial 901 model were those that were far from the public eye. The first was the considerable improvement in the car’s autonomy compared to Porsche’s predecessor models, with the 901 having a 62-liter tank, compared to the 52 liters of the 356A.

But the big difference between the 901 and not only the 356, but all its market rivals, was its performance. With a maximum power output of 128 bph, the Porsche 901 could accelerate from 0-100km/h in 9.1 seconds, reaching a top speed of 210 km/h in its factory standard.

This performance was due to a masterstroke by Porsche. Initially planned to receive a completely new engine (a 2-liter 6 cylinder prototype engine known as “Type 745”), the Porsche 901 had to settle for an air-cooled flat-six boxer engine, a simple evolution of the old flat-four that equipped the VW Beetle and the Porsche 356.

What seemed like a simple stopgap for a failure by the Porsche engineering team turned into a major success story for the entire 911 family. The interesting thing is that although most of Porsche’s rival manufacturers initially disdained the car’s small engine, they soon had to retract their ideas, upon realizing that the small 901 was a superior car in almost every aspect to its category rivals.

A year would pass before the vehicle went into serial production, a period used to perfect the last details on the new Porsche model – including changing the vehicle’s name!

Even though the car was expected to continue bearing the Porsche 901 nomenclature, which it was presented in 1963, it didn’t take long for the vehicle’s code to arouse some envious looks. The marque which was most uncomfortable with the situation was Peugeot, which, at the time, claimed to have in France the exclusive commercial rights to car names formed by three numbers with a zero in the middle.

Due to the intention of marketing the vehicle also in French territory, and to avoid entering into a legal dispute with Peugeot, the 901 was rebranded 911, the name under which the vehicle would become recognized worldwide.

In September 1964, the first Porsche 911 rolled out of the factory line, the 901/911 “O-series” version. Sales were slow during the early production days, with only 82 Porsches from the first batch being manufactured.

Such numbers were far from what Porsche expected, especially considering the resources spent on developing the car. Therefore, it was necessary to find a quick and simple solution to help publicize the 911, attesting to the quality and performance of the new vehicle.

The answer would be the same as the one so successfully used by the Porsche in recent years: investing in motorsport.

MONTE-CARLO RALLY: WHY?

By the mid-1960s, Porsche was already a well-known name in motorsports. The constructor had already collected more than a hundred victories and trophies around the world, in touring, prototypes, hill climbing and even Formula 1 events. The Porsche name had already become deeply intertwined with motorsports, with the brand being a force in the most diverse disciplines of sport. So it is not a surprise that the automaker would once again opt for this route to promote its brand-new product.

So, it was a natural path that the 911 took towards motorsport, with the intention of entering the vehicle in some selected races in 1965. The problem was that, right from the start, the project faced serious limitations in getting off the ground.

Firstly, the budget of Porsche’s competition department was already almost completely reserved for the upcoming 1965 season, with the works 904 GTS continuing to be the company’s flagship cars in the World Sportscar Championship, and the 904/8 Bergspyder being the representative in the European Hill Climb tournament.

Furthermore, the development of Porsche’s next competition model, the 906, consumed another large portion of the automaker’s resources and attention, which turned the 911 project into the “ugly duckling” of the company’s motorsport department.

Due to these budgetary and personnel restrictions, there were few alternatives left for the 911 in 1965. One of them, the European Touring Car Challenge (ETCC) would soon be discarded too, due to the tournament’s financial obligations, while one-off races in the touring category not fitting the Porsche requirements, which wanted to show its vehicle in well frequented events.

Thus, the path was finally outlined for the 911 to make its debut as a rally vehicle. Although it may seem like a peculiar choice, it makes sense if one evaluates Porsche’s initial objectives, of demonstrating the potential of its vehicle in difficult conditions, in a great stage, close to the public and potential buyers.

Therefore, there was no better platform in the world of rallying than the very traditional Monte-Carlo Rally, which, in 1965, would be on its 34th edition. At the time, the event was considered the official start of motorsport seasons around the world, being the great test of endurance alongside the 24h of Le Mans.

Fortunately, the proposal found strong support from Fritz Huschke von Hanstein, Porsche’s sporting director and head of public relations of the company. Von Hanstein knew that a good campaign in the Monegasque Rally could positively boost the brand’s image, especially as he himself was a former racing driver, knowing very well the challenges and prestige of Monte-Carlo.

Von Hanstein’s endorsement in the fall of 1964 kicked-off Porsche’s preparations for the rally, which was scheduled to begin on January 16, 1965.

The first step in the team formation process for Monte-Carlo would be choosing the drivers who would drive the 911. These were hand-picked by Huschke himself, who was eager to have a great line-up that could increase the 911’s chances of survival in the race.

And the names really proved to be of the caliber of Porsche’s project. As the main pilot, Herbert Linge was selected. Linge, 36 years old at the time, had been a regular Porsche driver since the early 1950s, having appeared to the world in the 1954 Mille Miglia, when he finished 6th overall (and first in class) in a Porsche 550.

By the end of 1964, Linge was one of the team’s most seasoned drivers, having driven for the brand in some of the most prestigious races in the world, such as the Carrera Panamericana, the 12h of Sebring, the 24h Le Mans and the Targa Florio.

Peter Falk was chosen as Linge’s navigator for the contest. Falk was everything Linge could have wanted by his side along the tortuous Monte Carlo Rally: as well as being a Porsche engineer and test driver since 1959, Peter had other great qualities at his disposal.

Falk had good experience as a co-driver, having participated in several international rallies between 1956 and 1958, alongside German driver Alfred Kling. If that wasn’t enough, Peter participated as a driver in small German club races at the Nürburgring in the early 60s, driving a DKW/Auto-Union 1000.

With the drivers ready for the adventure that was to come, it was time to select the car that would take part of the expedition.

The choice fell on one of the standard models of the 901/911 “O-series”, the chassis 300055, which would be known as “R1” for sporting purposes. The car, in ruby red, was carefully selected by Linge and Falk while it was still on the production line. In addition to the extravagant exterior color, the vehicle had a pepita-style artificial interior leather, giving this Porsche model a unique charm.

As soon as the vehicle was delivered to Porsche’s competition department, preparation work began. The first changes made were the removal of some extra weight from the machine, so that the necessary updates for the rally could be accommodated.

Once this stage was completed, changes began to be made to the mechanical part: the installation of a larger fuel tank (with a capacity of 100 liters), an update to the braking system (so it could withstand and react equally in the different weather conditions of the race), in addition to the installation of a rear anti-roll bar, to help with the vehicle’s stability and performance.

However, the biggest modifications at Porsche 901/911 “R1” were in the engine, exhaust and transmission systems. The “Type 901/02” engine was completely modified for the race, with the installation of polished ports, Weber carburettors (instead of the standard 901/911 Solex Carburetor) and platinum spark plugs.

The engine compression ratio was improved from 9.1 to 9.8:1 ratio, and the power output rose from 130bhp at 6100 rpm to 150bhp at 6600 rpm. To help with the car’s control and traction, Porsche modified the standard five-speed transmission to include a ZF limited-slip differential, sensibly lowering final drive ratio and competition clutch.

In the car’s collection and emission system, a free-flow exhaust was installed, which significantly improved the engine’s efficiency.

In terms of aesthetics, the Porsche “R1” looked identical to any “O-series” production model, with only sensitive changes made for the sake of safety and driver requests: inside the car, a roll cage had been installed, together with some timekeeping watches, and the gear lever was moved a little back, due to a request made by Linge.

In the bodywork, the only noticeable changes were the installation of a set of Marchal spotlights. Two were installed on the car’s bonnet, while one was on the roof of the vehicle – which was rarely used, being activated only to read traffic signs in poor visibility conditions.

With the project already at an advanced stage, Linge and Falk took the 901/911 for its first trials in late autumn of 1964. The first test was a simulation of the route the pilots would take, between Frankfurt and Monte-Carlo. The car demonstrated extreme robustness, completing the route without any major problems.

Next, the vehicle was dispatched to Monza, to carry out some experimental runs in more controlled conditions, in which Porsche could finally see some points of improvement in the vehicle. The last test took place at the end of 1964, with Linge and Falk once again traveling the rally route, covering Germany, Belgium, France and the Principality of Monaco.

At the beginning of 1965, the Porsche 901/911 “R1” was ready for the challenge that would define its career: would the car be remembered simply as an interesting passenger car – or as a vehicle with immense competition potential?

A CROSS-COUNTRY ADVENTURE

The Porsche contingent at the 1965 Monte-Carlo Rally was not only represented by the 901/911 “R1”. Furthermore, the Porsche team also consisted of another car: a 904 Carrera GTS, driven by Eugen Böhringer and co-driver Rolf Wütherich. As a special reinforcement, there was also a semi-works 904, registered by the Finn duo Pauli Toivonen and Antti Arnio Wihuri.

It was all part of Porsche’s plan to maximize efforts using as few resources as possible. This point was extremely necessary, as the manufacturer expected strong opposition from much more established teams in the rally scene, such as BMC (Mini), Citroën and Saab.

However, the order given by the team was not to force the way against their rivals. For the Linge/Falk duo, von Hanstein gave as the main objective to take the 901/911 intact until the end of the rally – a task defined more important than the victory in the race itself.

It is worth remembering that, at that time, the Monte Carlo Rally did not have a single starting point, with groups of cars making their way to the Principality from different points across Europe. The Porsches were part of the German starting pack, composed of 26 cars.

The starting point of the german contingent was Bad Homburg (north of Frankfurt), taking a route that would bypass the Ardennes Forest towards Belgium and Holland, and then continuing south towards the Alps and then the Cote d’Azur.

The group departed towards southern France, in the second half of January. The first leg of the contest was marked by great difficulties. Unexpected snowfalls closed several main and secondary roads along the path of the group, preventing some parts of the route from being properly followed. Furthermore, the dangers of the snow materialized in several accidents among the contingent, with only 21 cars reaching the rally’s first common control point, in St. Flour.

The second common checkpoint was the town of Saint-Claude, in the Jura department, with the drivers later progressing to Chambéry. It would be in this small town, at the foothills of Mont-Blanc, that the teams would have their first moment of rest in the entire race, with a 30-minute stop being allowed to refuel and change tires. At this point, it was clear that the 1965 Rally would be one of the most difficult in history: of the 237 starters, only 159 remained in contention.

So far, the Porsche team was doing well in the standings: the 904 GTS of Böhringer/Wütherich was in the front-5, while the 901/911 was in the top-10. Toivonen/Wihuri were also in a strong position, even after some problems on the route to Chambéry. But the stop in the small French city would only be a short breather, with the teams plotting their course towards their final destination: Monaco.

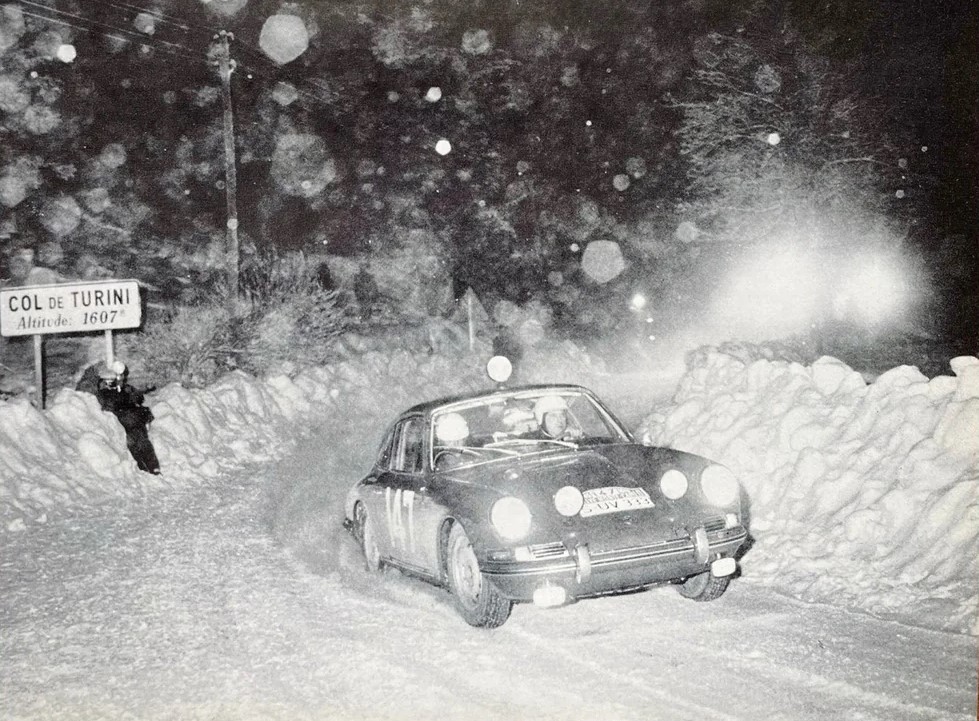

Much of the route from then on would pass through the Alpes-Maritimes, on a treacherous path that was known to be completely covered in snow and ice. Leaving Chambéry at nightfall, the Porsches found themselves trapped in a large web, which baffled all the rally drivers alike: visibility approached zero, while snow and darkness embraced the vehicles.

Little by little, the peloton began to be decimated, due to mechanical problems, accidents, punishments and drivers who simply got lost in this confusing situation. One of these victims would be the Toivonen/Wihuri duo, due to mechanical problems.

After Gap, which would be the last reasonably sized city before Monaco on the route, the situation became even more complicated, with the snow becoming almost impassable on several roads. Even so, the platoon continued crawling forward, inexorably towards the sea.

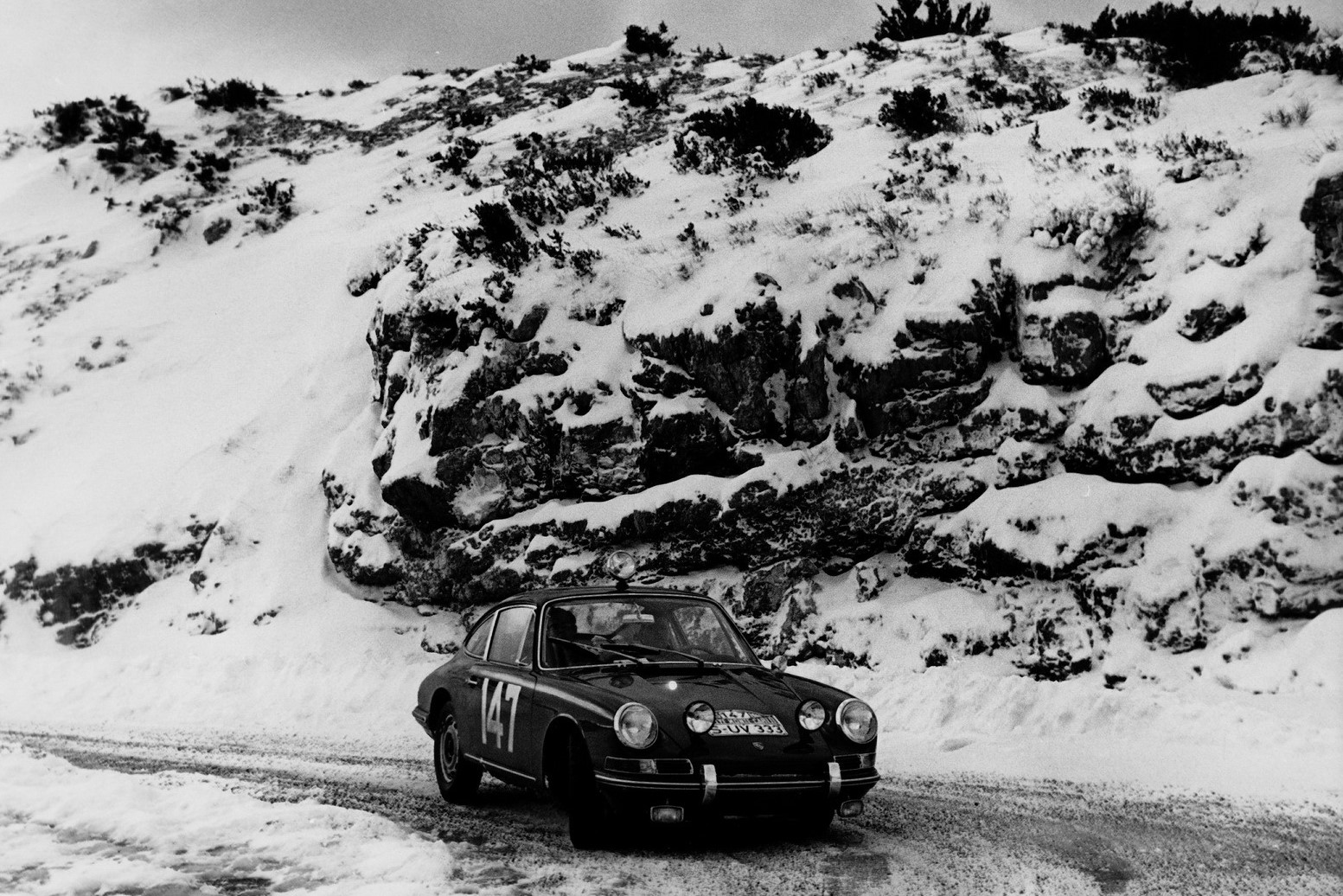

It would be in this part that the 901/911 almost followed the path of the Finn 904, spinning and crashing due to the slippery road conditions. Luckily, Linge was able to recover the car quickly, with the collision resulting in just a small scratch in the front of the Porsche. After that scare, Linge and Falk decided to be more restrained in the race. The duo was already in an excellent position, floating between sixth and seventh places, well above what was expected for the 901/911.

One of the reasons that led to this lessening of the drivers’ appetite was that the final section of the rally, just over 610 km long, was still to be completed, and was admittedly the most difficult and technical of the entire route. It included the ascent of the Col du Granier, the passage of the mythical Col de Turini, as well as the descent to Monte-Carlo from the French Alps.

Despite keeping a set of new tires just for this section, both Linge/Falk were deprived of using the new compounds, to the detriment of the Böhringer/Wütherich duo, who, at that moment, were fighting for the overall lead of the race. Without the promised tires, Linge could only be content to overcome such challenges in a relaxed manner, without risking too much.

Luckily, some drivers in front of him had problems, such as the duo Lucien Bianchi / Jean Demortier, from Citroën. The Frenchmen were second in the standings when they collided with a tree on the final descent to Monte-Carlo.

So, when the 901/911 crossed the finish line, both Herbert Linge and Peter Falk were surprised to learn that they had finished fifth, a spectacular position considering the difficulties faced by the pair after the journey of more than 2000 kilometers across Europe.

The duo finished second in their class (2/4), behind only the Porsche of Eugen Böhringer and Rolf Wütherich. The Stuttgart manufacturer’s result was even better as a whole, since Böhringer was second in the rally’s overall classification.

The winner of the race was the duo Timo Mäkinen and Paul Easter, who, aboard a Mini-B.M.C., achieved the second consecutive victory of the British car manufacturer in the Monte-Carlo Rally. A great achievement for little Minis!

A LEGACY OF SIX DECADES

The 1965 Monte-Carlo Rally attested the great design qualities of the Porsche 911, just as Ferry Porsche and Huschke von Hanstein wanted. The car had withstood one of the most atrocious races in history, as of the original 237 vehicles in the field, only 22 reached the finish line in Monte-Carlo – an undeniable feat for the then unknown German car.

Both the media and rival automakers now began to appreciate the characteristics of that vehicle, which was now positioned as one of the giants of the automotive industry. Although the 901/911 “R1” was a one-off project, its performance in its only race would have a lasting effect, showing that the 911 was not a car solely for the daily use of speed enthusiasts, but also, for those who wanted to have a real racing car in their garages.

This result encouraged Porsche to test a 911 at the 1965 Targa Florio, to see how the vehicle would perform in more conventional racing conditions. Although the 901/911 only took part in the race’s training sessions, with Umberto Maglione and Herbert Linge taking turns at the controls, it was clear that the 911 would also have a bright future on the track.

After the success in Monte-Carlo, the next great achievement of the 911 would take place at the beginning of 1966, when a 901/911 (chassis 300128) driven by the trio Jack Ryan, Lin Coleman and Bill Bencker, would win its class in the 24h of Daytona. This would be the milestone that would kick off the successful history of the 911 on race tracks around the world.

As for the 901/911 “R1”, what remained was its own myth, which would only be revived decades later: after the Monte-Carlo Rally campaign, the car would pass through a few hands, including a Munich dealer, a French driver and some other unidentified owners. It was only in 2013 that the “R1” would be saved from oblivion, being bought by a German collector who completely restored the car to its original 1965 rally pattern.

Therefore, it is undeniable that most of the 911’s successes would not have existed if it had not been for that ruby-colored Porsche 901, which rolled off the production line in the autumn of 1964. A car that forged the entire history of a model and which, 60 years later, greatly symbolizes the spirit of a brand.