The first post-war motorcycle was introduced in 1948 and sold well through its peak sales year of 1952, dropping quickly after that. The 501 baroque angel was put into production in 1952, but it was too expensive for most German families at that time and the styling was from the 1930s. A bigger engine and nicer trim for the 502 didn’t help much. The 503 and 507 were limited production shooting stars that lost money. From a financial perspective, all the 500-series cars were flops. Things were getting increasingly desperate for BMW.

German citizens after the war first used bicycles, then motorcycles and then microcars, which were essentially enclosed motorcycles. Searching for such a car, a representative from BMW attended the Geneva Motor Show in March 1954. There on display was the Isetta, meaning little Iso, a product of the Iso Rivolta refrigeration company of Milan, who had decided to put into production a microcar designed by an aeronautical engineer.

The front-opening door design had not caught on in its native Italy, so BMW representatives were able to not only license the design and name, but also buy the production line equipment, which had only produced about 1,000 vehicles for the home market. The production line was trucked over the Alps and installed in Munich, allowing BMW to start sales of the ‘little egg’ in 1955. From 1955 to 1962, BMW sold over 160,000 Isettas.

BMW then created a stretch version of the Isetta, the 600, with a rear seat and a side door. It was sold for three years, from 1957 to 1959, with about 35,000 units produced. The odd styling ensured it was another flop.

BMW management never saw the Isetta or 600 as “cars.” They were stop-gap efforts that might help the company get to the real goal, a mid-sized, conventional car. This was the goal throughout the 1950s, but the company was undercapitalized after the war and continued losses made the financial situation ever worse. It didn’t help that management was at times timid, inept and arrogant. Quite a combination.

The 700

The internal development department tried to stretch the chassis of the 600 further in order to accommodate a more conventional-looking car. This proved impossible, but the engineers—and the accountants for that matter—wanted to use the suspension and drivetrain that had been developed for the 600. Fritz Fiedler, the legendary engineer from the 1930s, clung to the “rightness” of the 600, despite the market not accepting the car.

Enter Wolfgang Denzel, the Austrian importer for BMW and an engineer himself. Denzel was commissioned by the BMW CEO to develop a car outside the normal BMW process. Denzel, in turn, asked Albrecht Goertz, to do a modern small-car design. Goertz had done the beautiful 503 and 507 for BMW. Goertz’s fee was too high for the struggling company, so he recommended his friend, Giovanni Michelotti, who got the job.

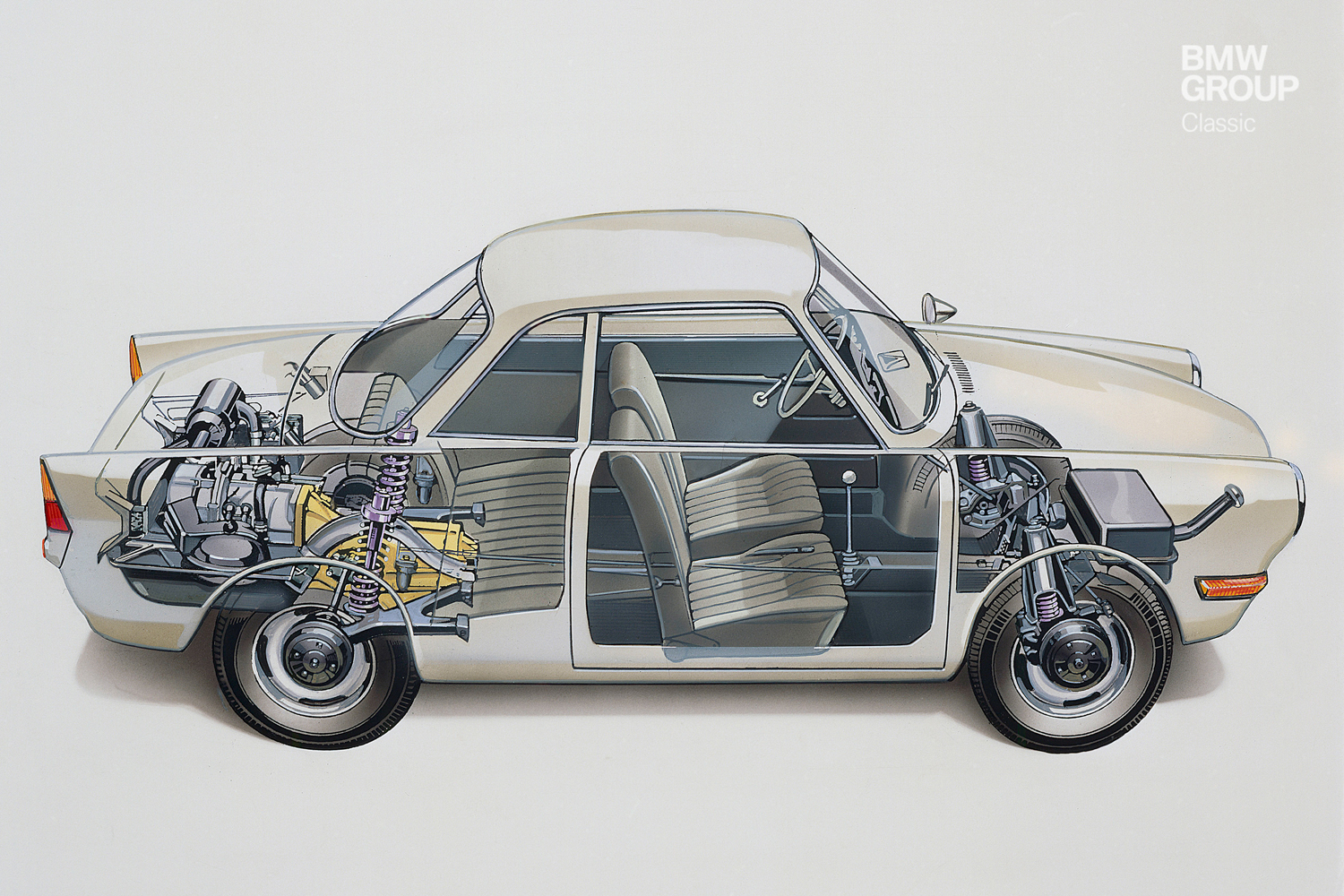

Michelotti’s prototype used the mechanicals from the 600, with the engine enlarged but still in the rear, and wrapped them in a unibody design that sidestepped the problem of further stretching the 600’s chassis. It became BMW’s first unibody car.

While Michelotti’s coupe prototype went into production in virtually unchanged form, BMW internally developed a two-door sedan version and then followed with the 700 LS (Luxus), 700 Sport/CS and finally, the lovely 700 Sport Cabriolet. The 700 was the first BMW to feature the Hofmeister kink, the rear window line that has been the hallmark of all BMWs since then. Hofmeister was the head of BMW Design at the time.

The opposed two-cylinder engine started at 30 horsepower, was uprated to 40 hp in the sport version and eventually reached 70 hp in racing versions, known as the 700RS.

Presentation to the Press

On June 9, 1959, BMW’s Board of Management under their Chief Executive Dr. Heinrich Richter-Brohm made the big move, presenting the new BMW 700 Coupé, the first model in the new series, to some 100 international motoring journalists. This was in Feldafing, near Munich, at the same place where about two years before they had first seen the not-so-fortunate BMW 600.

The minute the new Coupé was revealed, everybody started clapping. The journalists immediately admired the new model. The BMW 700 had grown out of the small car class still prevailing in the market at the time and allowed a relatively high standard of freedom in providing extra space. The designers and engineers were particularly proud of the car’s consistent lightweight technology reducing dry weight to less than 600 kg or 1,323 pounds despite the car’s overall length of 3,540 mm (139.4″), thus providing the qualities required for good acceleration and hill-climbing performance.

Journalists driving the BMW 700 Coupé were – rightly – thrilled from the start, waxing lyrical about the car’s design and its driving qualities: “Acceleration is certainly impressive for a car of this size, taking you from a standstill to 90 km/h in 20 and to 100 km/h in 30 seconds.” Ultimately, most of the testers readily confirmed the optimism expressed by BMW’s Board of Management: “The BMW 700 Coupé is the latest model from Bayerische Motoren Werke and promises to be a great success and a real highlight at this year’s Frankfurt Motor Show.”

Frankfurt Show

This is precisely what happened, with the BMW 700 becoming a genuine highlight for the public in Frankfurt. The new Coupé was presented on the BMW stand at the 1959 Frankfurt Show at a price of DM 5,300 including the car’s heater. Right next to it was the four-seater Saloon based on the same engineering and design concept and destined to enter series production in early 1960.

With the Frankfurt Motor Show hardly over, BMW struck a very positive balance towards the end of September: “Both new models were warmly welcomed by motor journalists and the public alike, showing a response well beyond even our most optimistic expectations. As a result, we successfully made an unusually large number of sales not only in Germany, but also and above all in our export markets.”

Politics behind the Scenes

While the 700 was well received at the September 1959 Frankfurt Show and orders poured in, the financial situation continued to deteriorate. Daimler-Benz wanted to buy BMW and turn the plant into a parts-making facility. A deal was struck with management for what was called a merger but, in fact, was an acquisition. BMW wasn’t really a competitor of Daimler-Benz at the time; they just needed capacity. Financing had been arranged through Deutsche Bank.

The fateful board meeting occurred on December 9, 1959. The proposed purchase by Daimler-Benz was supported by management but opposed by the smaller shareholders, the unions and the dealers. The dealers would, after all, lose their BMW franchise when the company was absorbed into Daimler-Benz.

There was also some skullduggery that has never been explained. The development costs for the 700 should have been capitalized and written off over time. Instead, they were all expensed in 1959. The board meeting occurred in December, before the year-end audit might have uncovered this. The Daimler-Benz offer had a very short period for acceptance. And management neglected to disclose the 25,000 firm orders that had been received from their dealers. Clearly management was trying to make the deal happen.

The attorney for the dealers got the decision on the offer delayed, which effectively killed it. The problem of the company being undercapitalized remained. The Quandt family was the biggest BMW shareholder and had been in favor of the Benz offer initially. But they were impressed by the workers and the dealership network and switched their standing to favoring an independent BMW.

Subsequently, the Quandts recapitalized BMW so that orders for the 700 could be met. More importantly, they also invested sufficient amounts to allow development of the New Class, the car that set a new direction for the company and the predecessor of every modern BMW.

So did the 700 save BMW? At the very least, the Isetta and then the 700 bought the company time until the Quandt rescue. The Quandt family, now 60 years later, still owns 46.6 percent of BMW’s stock.

Interested in classic BMWs like the 700?

Join the BMW Classic Car Club of America (BMWCCCA) and receive their quarterly print magazine “The Ultimate Classic” produced by the publishers of Vintage Road & Racecar.

The Club’s mission is to promote the interest in, the ownership of, and preservation of classic BMWs, as well as to encourage their use and visibility.

http://www.bmwccca.com/

Facebook @bmwccca

email: [email protected]