Hot on the heels of its creation of the World Drivers’ Championship in 1950, the FIA turned its attention to sports-car racing. Endurance races like Le Mans and the Mille Miglia were acknowledged as great classics but no championship linked them in a manner that might excite both racing fans and participants. That changed for the better in 1953 with the FIA’s establishment of the World Sports-car Championship. Rightly enough it was for car makers, not drivers.

Here was fresh inspiration for the world’s builders of sports-racing cars. Jaguar, Aston Martin, Cunningham and Mercedes-Benz took notice. In the new trophy’s first season, 1953, points were awarded for finishes in the Sebring 12 Hours, Mille Miglia, Le Mans 24 Hours, Spa 24 Hours, Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometers, Tourist Trophy and Carrera Panamericana. While the races in Florida and Mexico were newcomers, the others were great international events. Success in the new championship would bring major kudos and act as a spur to sales. How would Ferrari respond to this new challenge and opportunity?

By the end of 1953 Maranello had its answer ready. Having benefited from chief engineer Aurelio Lampredi’s punchy four-cylinder engines in his Grand Prix cars, Enzo Ferrari approved Lampredi’s plan to extend the technology to larger dimensions for a new 3.0-liter sports-racer. This continued the gradual enlargement that began in 1952 with a 2.5-liter four for the Type 625 in preparation for the new G.P. Formula coming in 1954. Such engines were installed in two Vignale-bodied spyders that had brief racing careers in Europe in 1953 before being sold to South America.

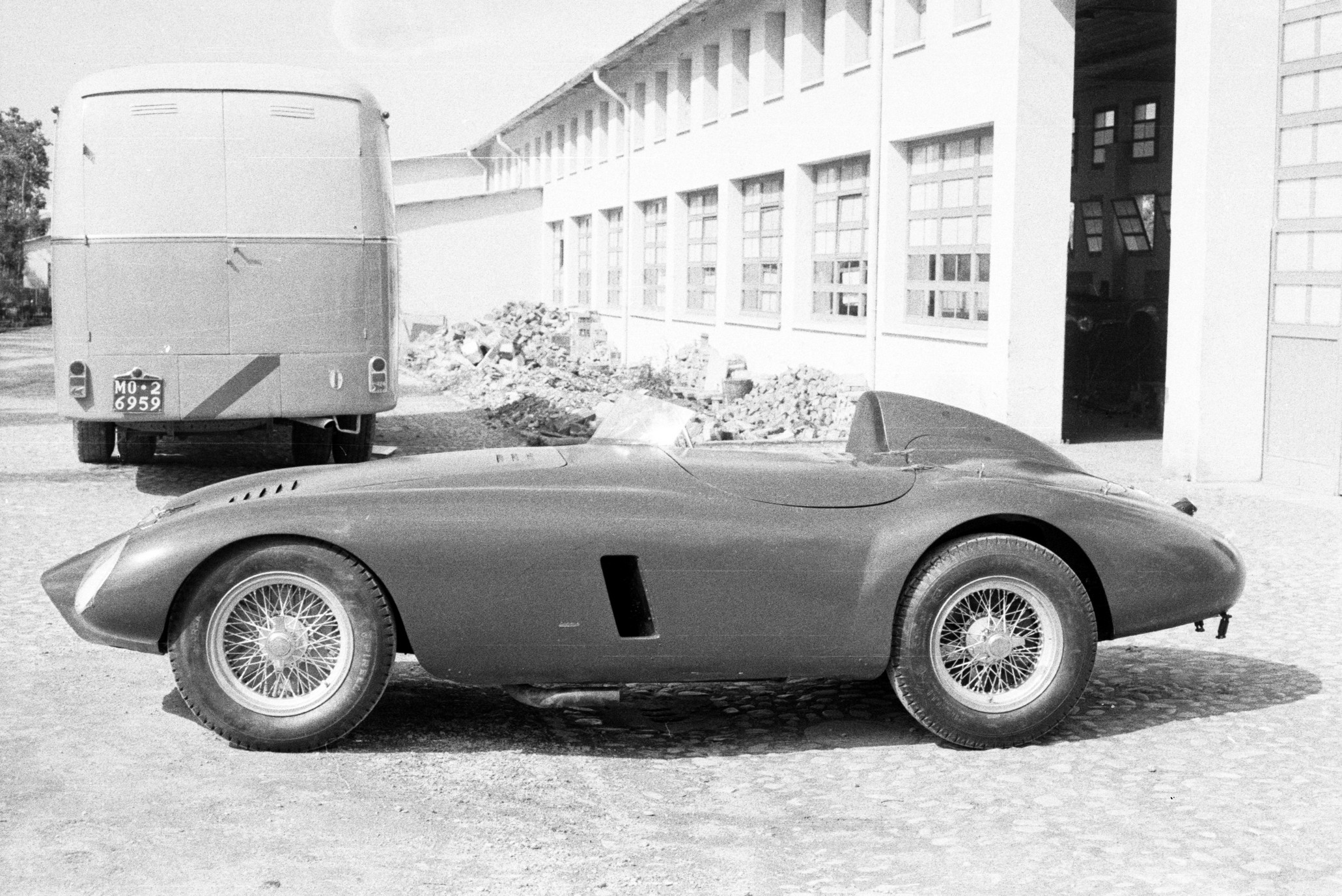

An even bigger four nearing three liters was installed in an open sports-racer bodied by Modena’s Autodromo to a design by Lampredi. Making a transition to Lampredi’s definitive four, still using the original architecture, this was known as the Type 735S. It had 102 x 90 mm dimensions for 2,942 cc and produced 225 bhp at 6,800 rpm. Early cars had bodies by Autodromo, Vignale and Pininfarina.

A spyder version of this Type 735S made a promising appearance at Senigallia on August 9, 1953. Thereafter Alberto Ascari drove a sister at Monza but crashed when avoiding another car. In January of 1954 the Senigallia 735S was taken to an endurance race in Buenos Aires, where it had the measure of one of the 4½-liter Ferrari twelves until the four’s torque shattered its final drive after a pit stop. A newly built 735S was driven to a conservative fifth place.

Early in 1954 Lampredi developed the new model in parallel with Ferrari’s struggles with Mercedes-Benz on the Formula 1 circuit. For a warm-up on May 22 Biondetti won the three-hour race at Bari. The full Type 750’s first racing appearance was on June 27, 1954 at Monza, where Mike Hawthorn and Umberto Maglioli took first and Gonzales/Trintignant second in the 1,000-kilometer Supercortemaggiore sports-car race.

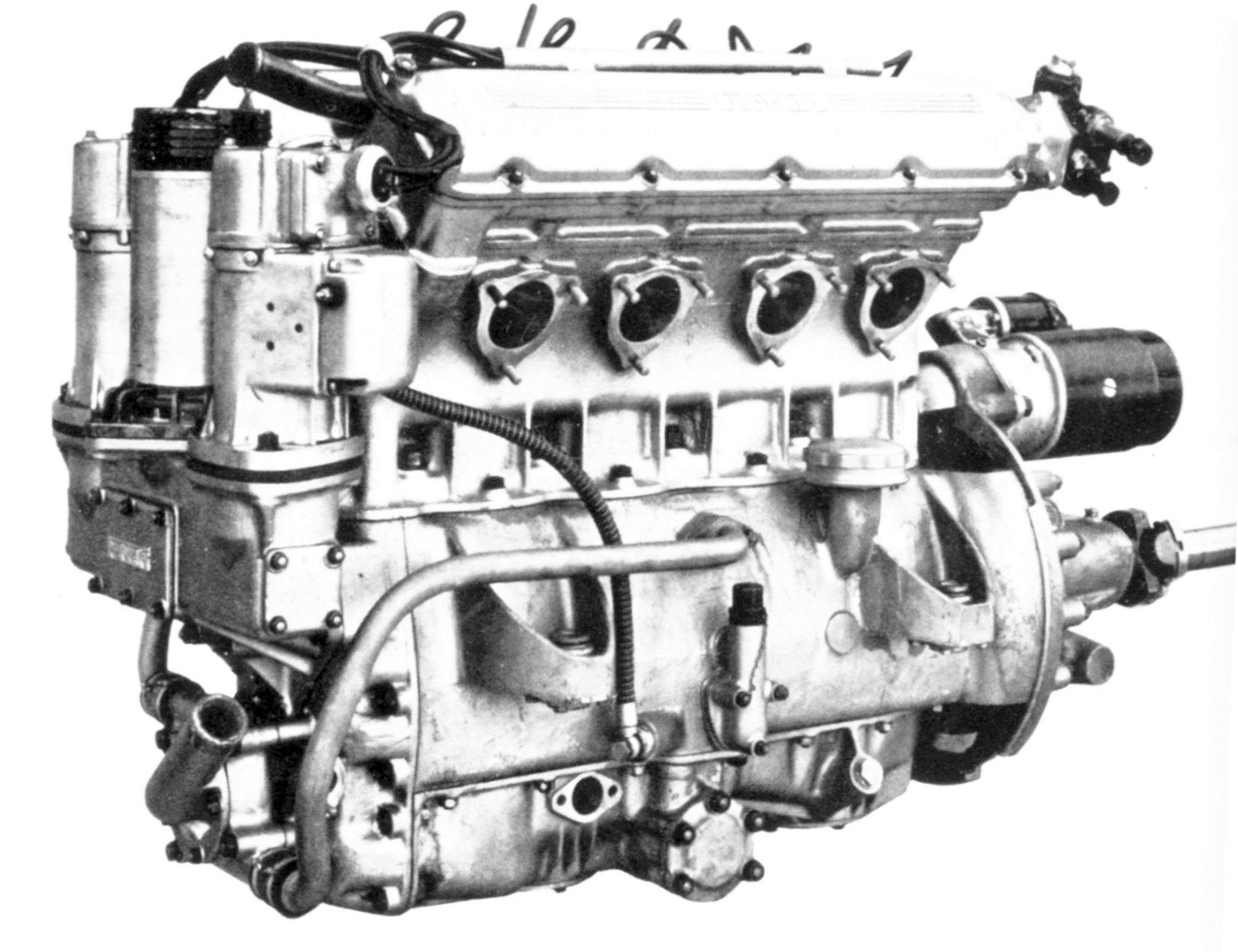

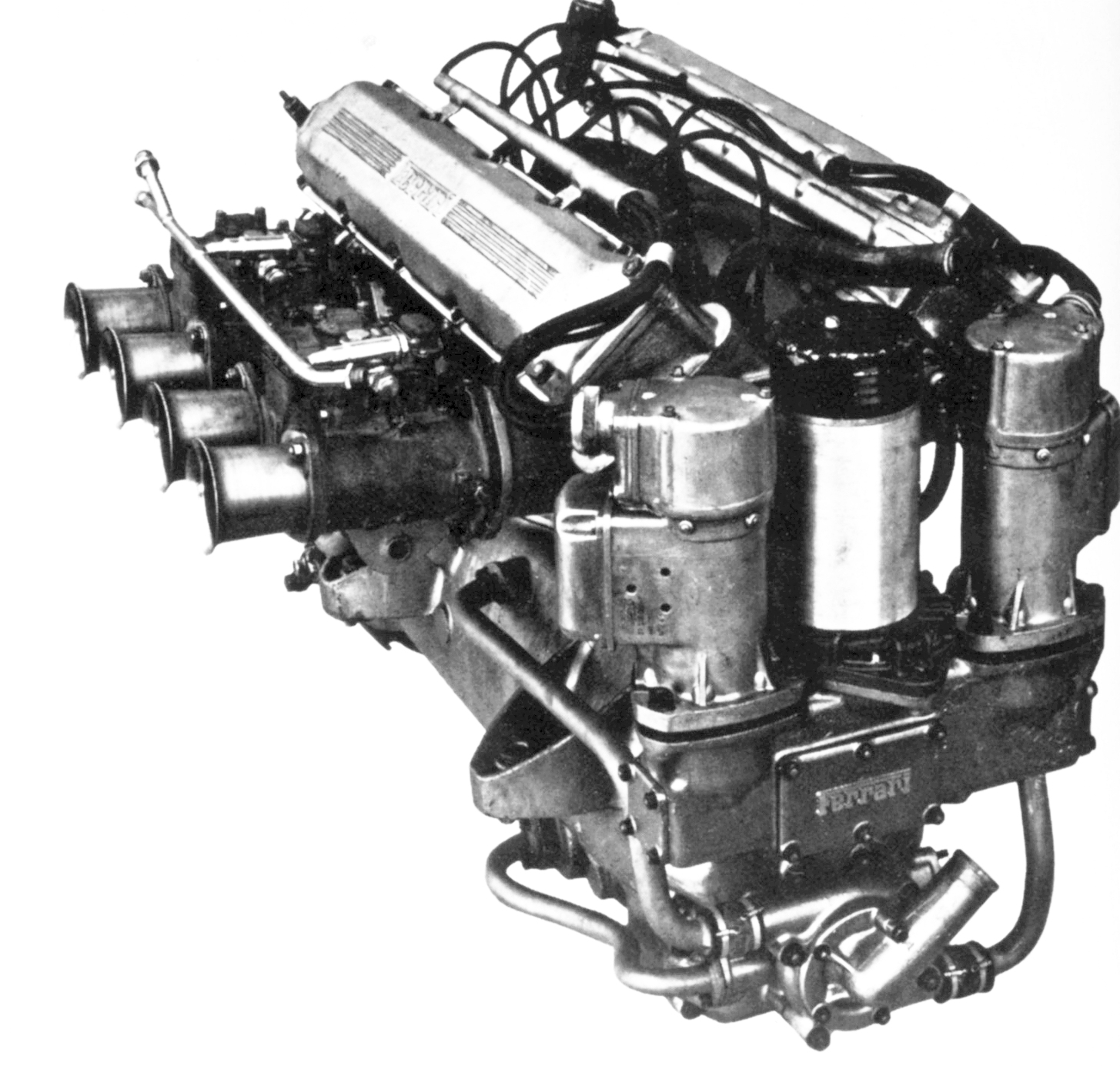

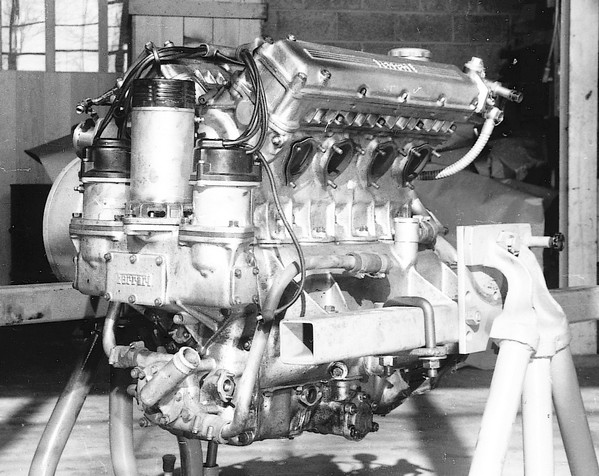

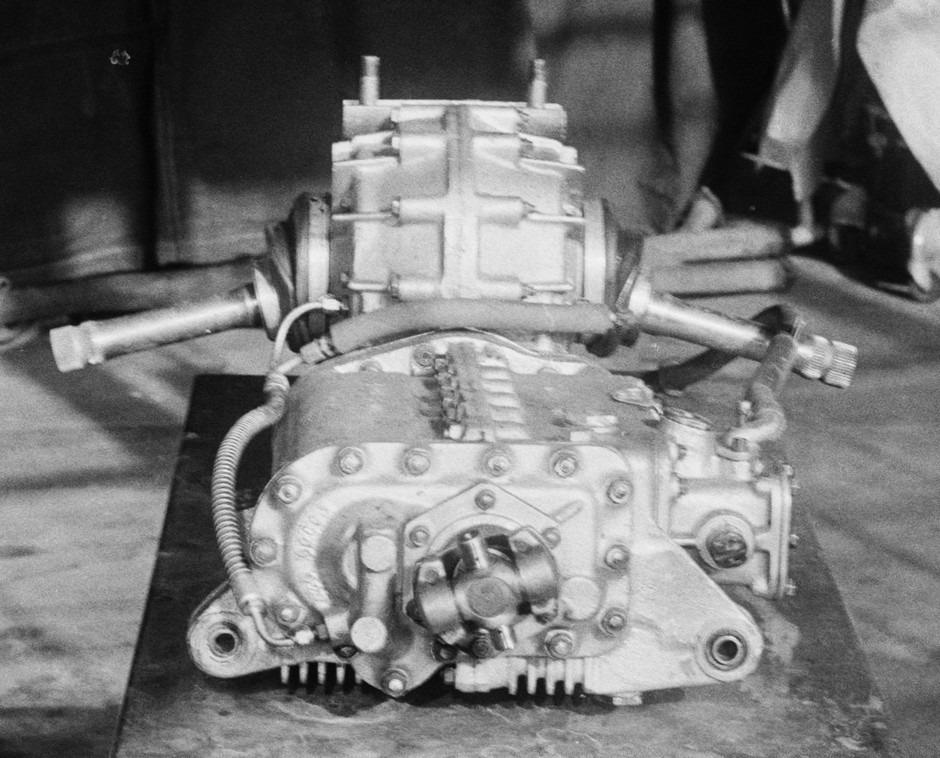

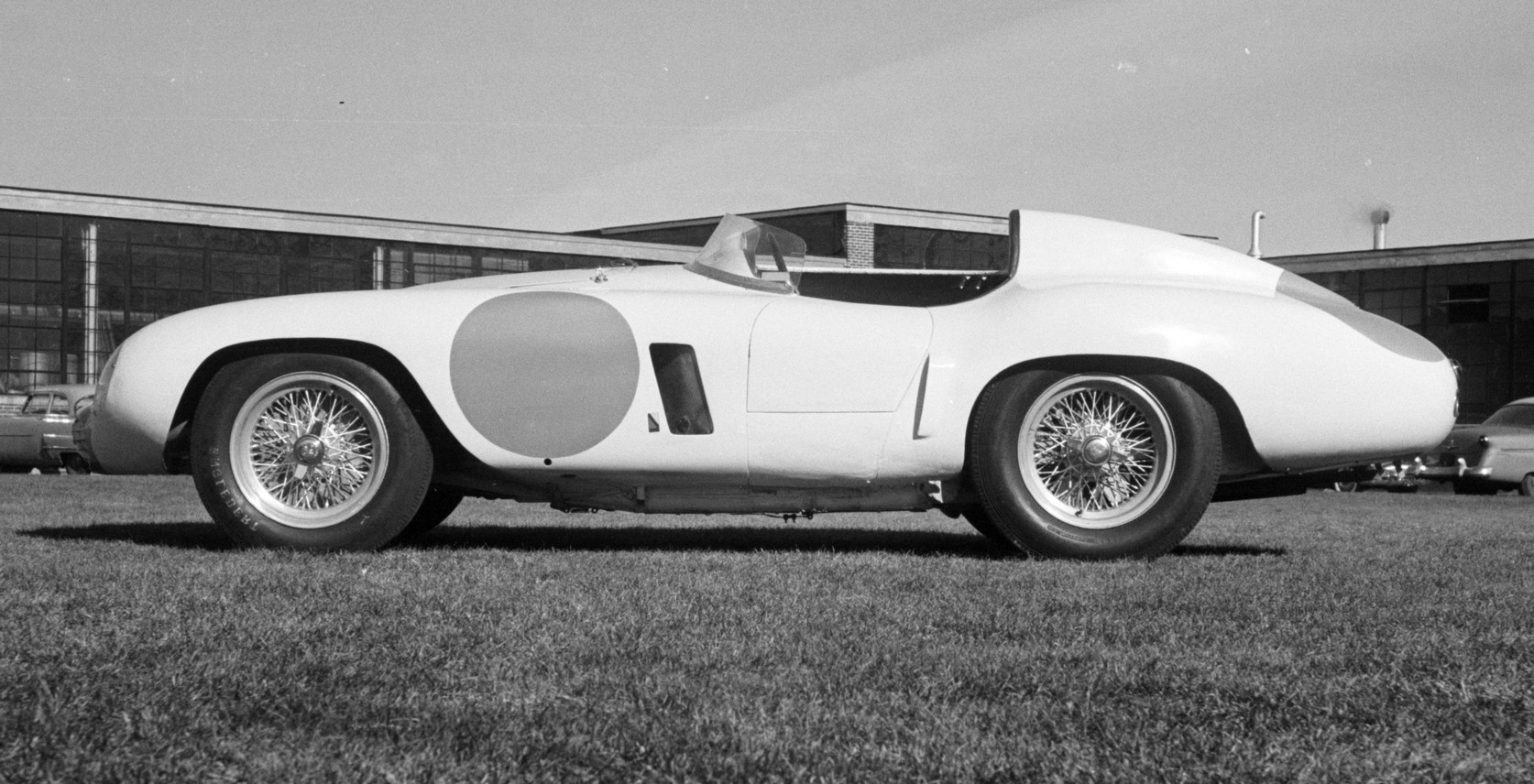

In the light of this impressive showing the newly christened “Monza” was overhauled for a tranche of production in the winter of 1954-55. The main line of development was via its engine, which the Ferrari drawing office called Type 105. In classic Lampredi style its head and cylinders were integrated in an aluminum casting which included the ports, combustion chambers and water jackets but not the cylinders themselves, which were separately cast of iron and screwed up into the chambers. Dimensions were 103 x 90 mm, daringly close to the Class D limit at 2,999.6 cc.

By any standards this was a remarkable engine. Here was a four-cylinder unit with as much swept volume as many of Ferrari’s twelves! A twelve-cylinder engine of similar cylinder size would displace nine liters! Not since the years before World War I had a serious European racing car been powered by such a huge four-cylinder engine. As a big four, in the racing world its only rival in the 1950s was America’s Meyer-Drake Offy. The latter’s bore size of 4.375 inches, 111.1 mm, was only slightly larger than that of this astonishing Ferrari.

While the Offy had the advantage of four valves per cylinder, unfashionable in the Europe of the 1950s, the Monza made do with two vast valves. Inlets of 50 mm were inclined at 45° from the vertical and 46 mm exhausts sloped at 40°, the latter having sodium-filled stems. The combustion chamber was a modified hemisphere with dedicated contouring around its two spark-plug holes.

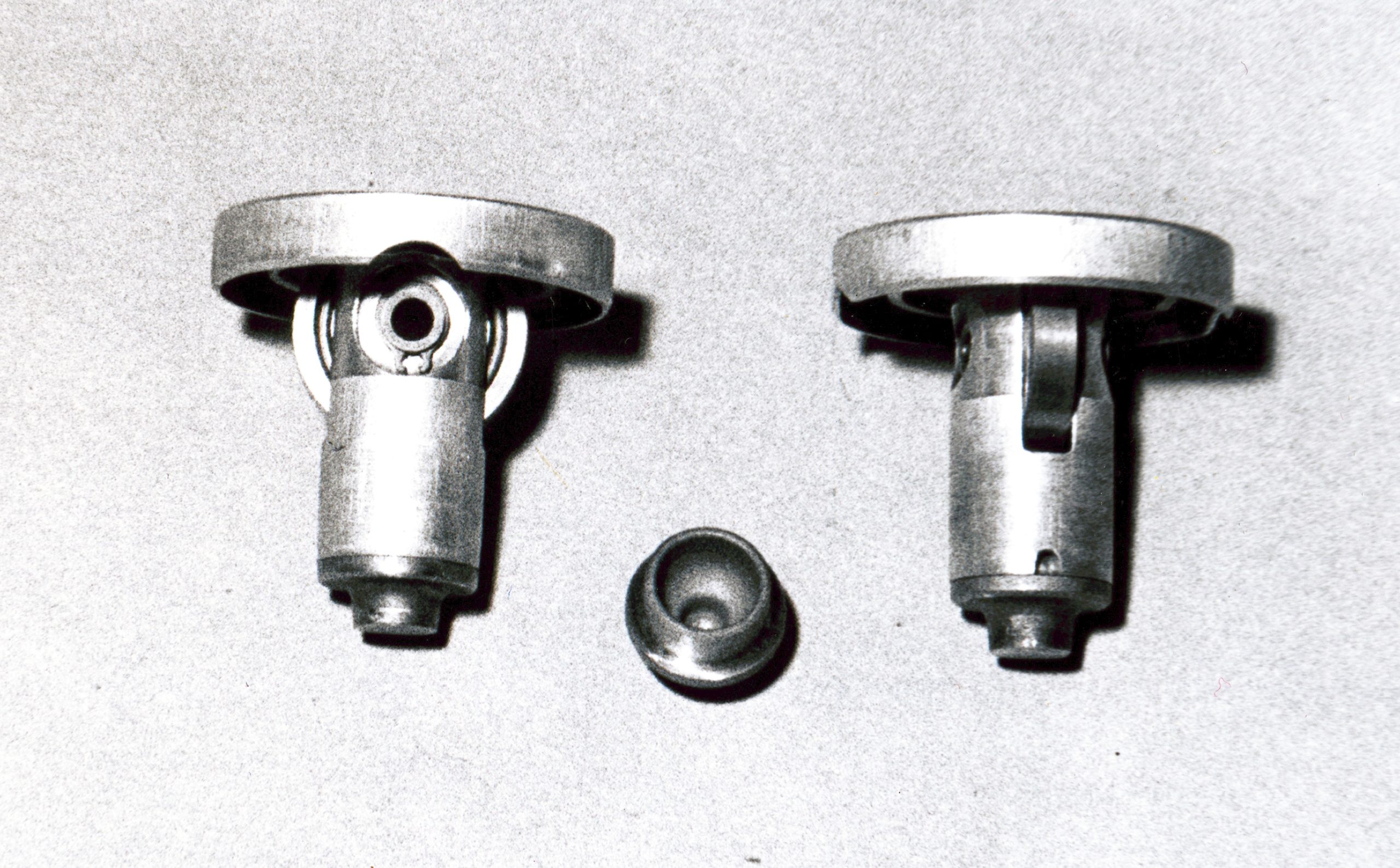

Lampredi’s proven techniques were incorporated in the Monza’s elaborate valve gear. Placed in a fore and aft plane, twin clothespin springs closed the valves through a collar retained by split keepers. Above this the tappets and camshaft were carried in separate cast light-alloy boxes. Accounting for the unusually high and wide Monza cam boxes, the separate tappet boxes allowed thorough lubrication of cam and followers without forcing leakage down the valve stems.

T-shaped in cross section, light-alloy tappets were guided by their stems and carried narrow rollers that protruded only slightly from their wide tops. Lower parts of the rollers rode in vertical slots and thus prevented the tappet from rotating. A pair of concentric coil springs acted against each tappet only, leaving the clothespin springs to cope solely with the valves.

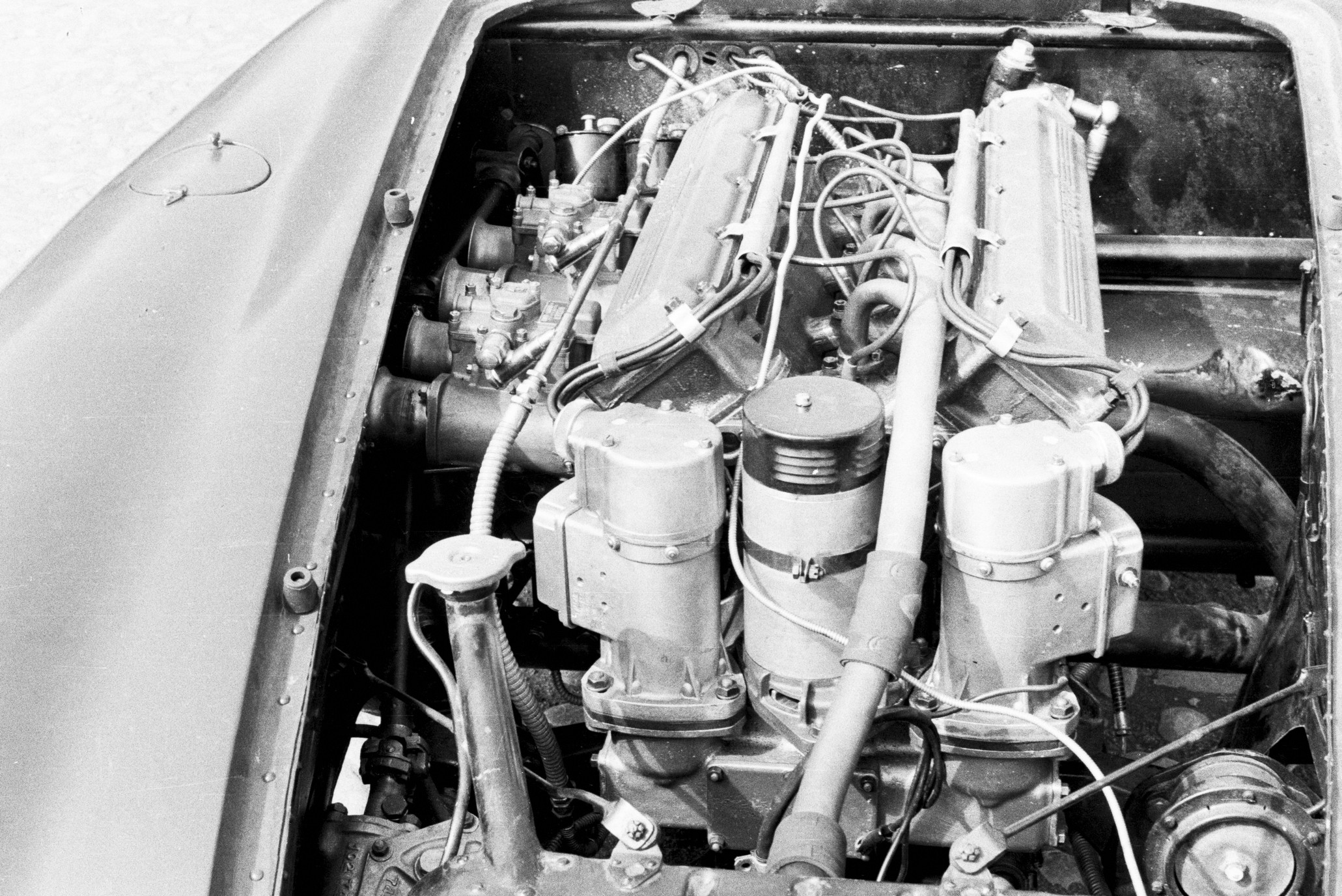

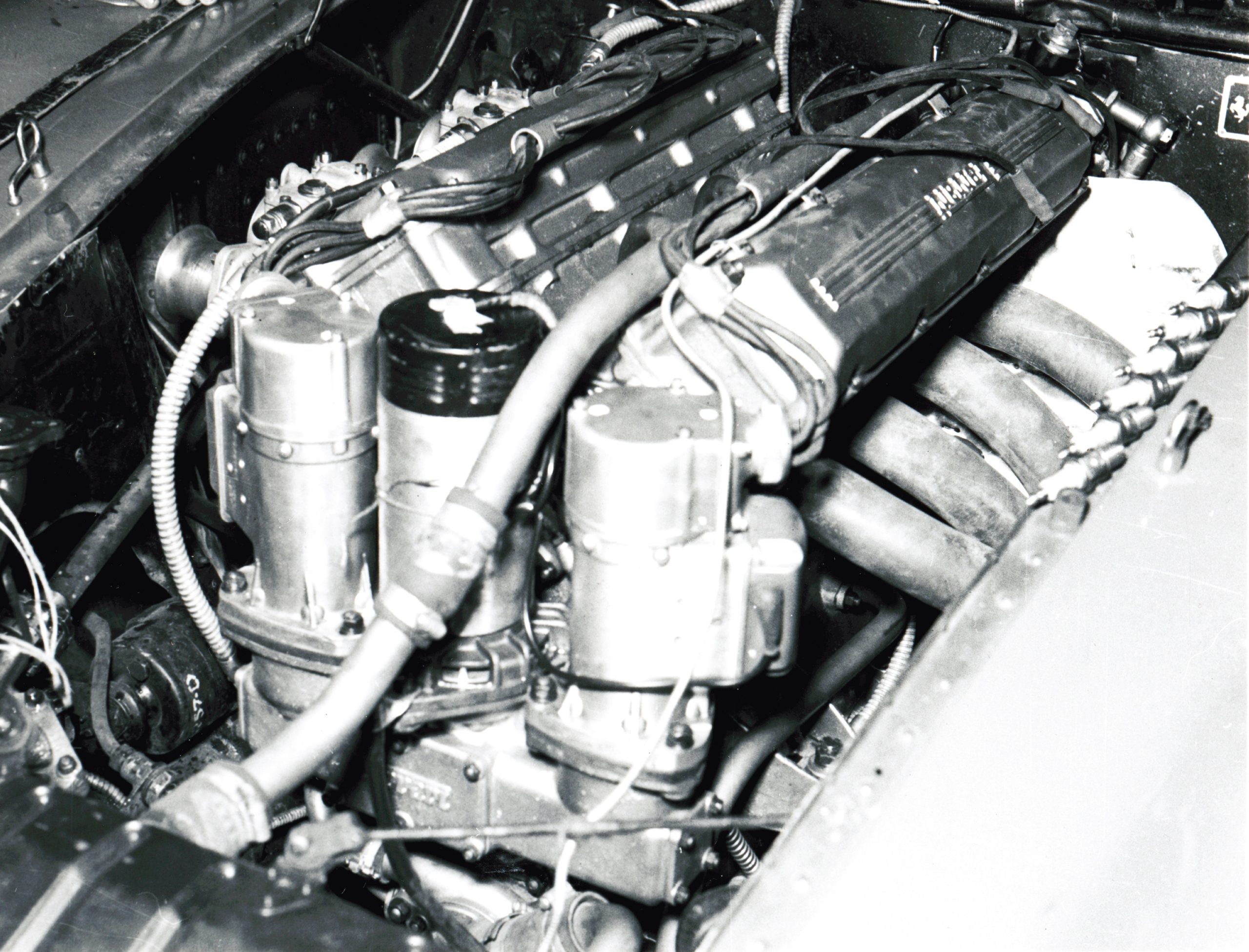

This belt-and-braces system kept the valves in contact with cams lobes 3/8-inch wide that provided 310 degrees of inlet duration and 98 degrees of overlap. Induction was by two 58 DCOA3 Weber twin-throat carburetors, the largest Weber made for cars, fitted with 44 mm venturis. Paul Frère quoted a volumetric efficiency of over 100% at 5,000 rpm for the similarly equipped Ferrari Grand Prix engine, which would have been approached by careful intake and exhaust tuning on the Monza. Short angled aluminum pipes connected the gasworks to their ports. A heavy throttle-linkage cross shaft was carried in two ball bearings. Exhaust porting was impressive, the outer opening being flared considerably from the size at the valve.

The head-cum-cylinder assembly bolted directly to the very deep Silumin crankcase, with rubber O-rings forming water seals at the bottoms of the individual cylinders. Solid webbing supported each of the five 60-mm main bearings. Devoid of elaborate balance weighting, the Monza’s forged-steel crankshaft carried 50-mm big-end journals.

Connecting rods were short and simple, the sides of the I-section center being perfect tangents to the outer diameter of the wrist-pin end. Two bolts retained the big-end cap, while the fully floating wrist pin received lubrication from splash alone. Pistons were completely skirted and carried two compression and two oil rings, one of the latter below the wrist pin.

An aluminum cover at the engine’s front concealed the accessory and camshaft drive train of 3/8-inch-wide spur gears. Upper gears dealt with the cams, while the water and oil pumps were placed low down at the front. Lubrication was dry sump, two screened pickups scavenging the front and rear of the intricately finned aluminum pan. The scavenging pump had two idlers to ensure that it kept up with the demand. It delivered to a riveted tank on the right-hand side.

A single-idler pressure pump drew from the reserve and replenished the mains through a sump-mounted full-flow filter. Typically Lampredi relied heavily on external and internal piping to carry oil around, not wanting to encumber his crankcases with too many cast- or drilled-in passages.

Simplicity marked the Monza’s cooling system, which was kept in motion by a twin-outlet pump adjacent to the scavenged oil supply. Drawing from the bottom of the gilled-tube radiator, the pump sent the coolest water to both sides of the crankcase, where it could absorb some heat from the main bearings. From there it rose past the cylinders to outlets directly above each combustion chamber. Thus the water is at its warmest when it reaches the exhaust valves, which do not receive a high-velocity cooling stream. The use of sodium-filled valve stems is thus vindicated.

An extension from the cam gear-train bevel drove a cross shaft within a magnesium box at the engine front. Further bevels rotated the central 12-volt generator and the Marelli distributors at each side. Earlier cars used magnetos while some of the Grand Prix cars used this bottom end with a cover plate in place of the generator. Coil ignition was ultimately deemed better for the Monza’smore moderate revs.

A Fimac mechanical pump driven from the rear of the exhaust camshaft supplied fuel to the back end of the carburetor system, while the front end was supplied by a rear-mounted Autolex electric pump. Four rubber mountings suspended the riveted-aluminum fuel tank.

In the transition from the 735S to the 750 the peak-power speed was cut back from 6,800 to 6,400 rpm, at the latter giving 260 bhp with a 9.0:1 compression ratio. Nevertheless the four big pistons continued to impose a high level of stress on the rest of the engine and drive train. Its construction was such that it could compete well in a 12-hour race but was seldom asked to survive the day-long Le Mans.

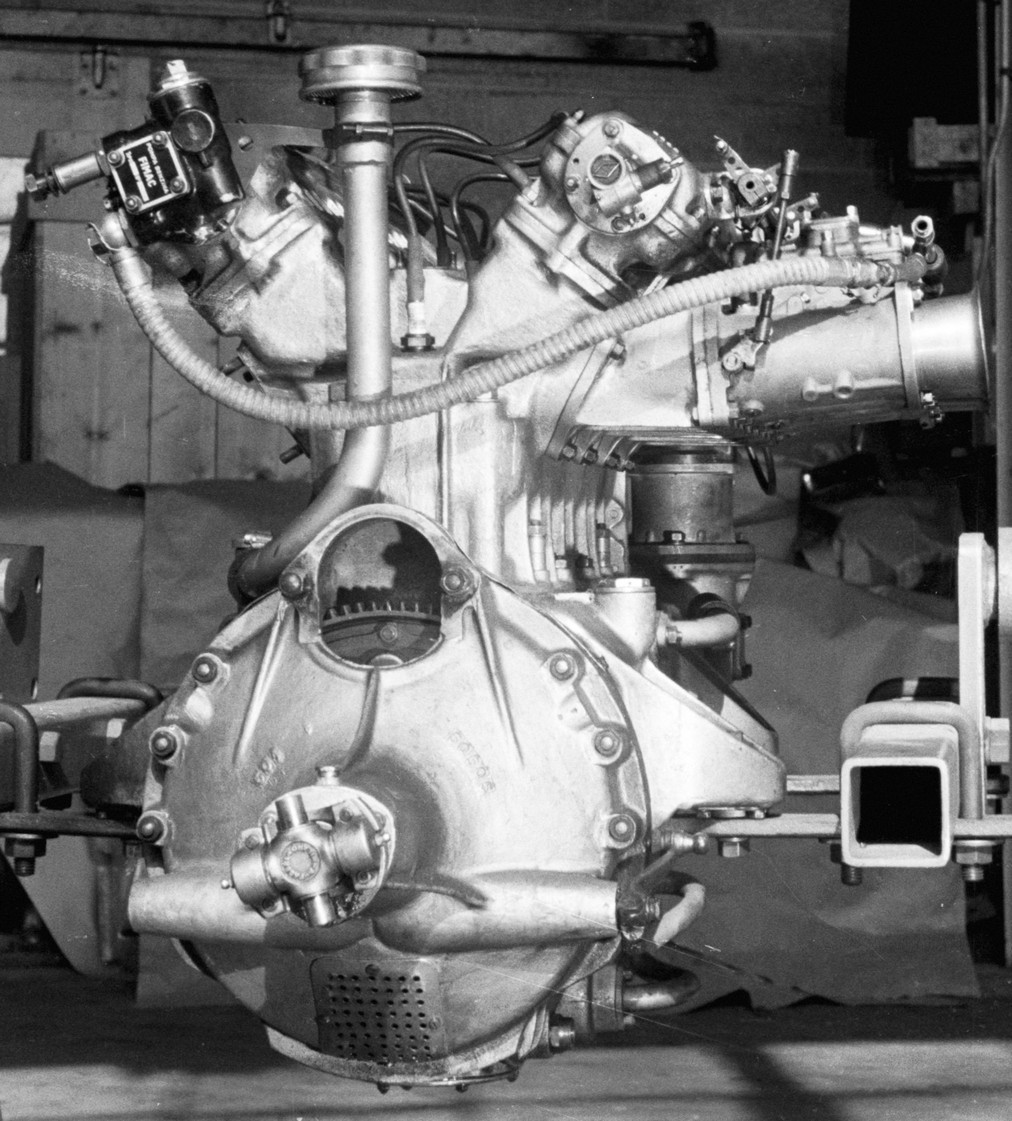

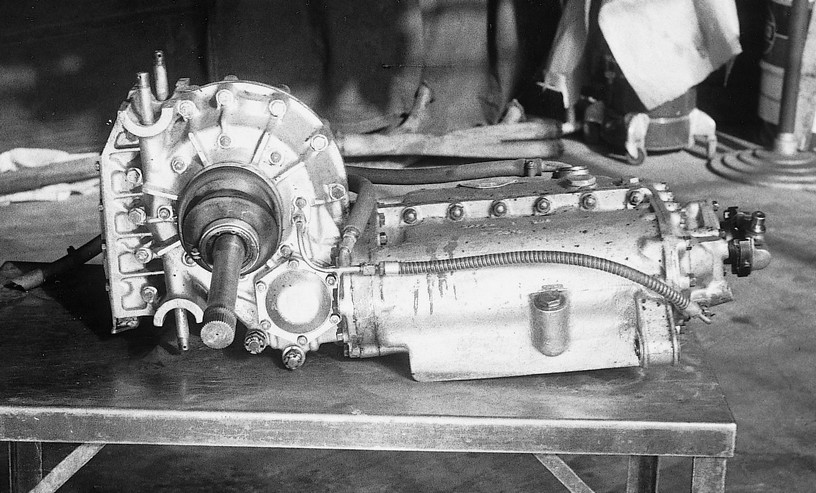

Placed just ahead of the final-drive gears, the transmission was split vertically in line with the mainshaft and carried the countershaft on the right and the selector mechanism on the left. Dog clutches engaged constant-mesh gears in the top four of the five speeds, while a jointed shaft transmitted the driver’s desires from the centrally placed shift tower. A compact conventional gate was used, with a reverse blocking latch. A few of the early type Monzas had four-speed boxes but the five-speed version was ready in time for early 1955 use on both the Monza and the Type 625 Grand Prix car.

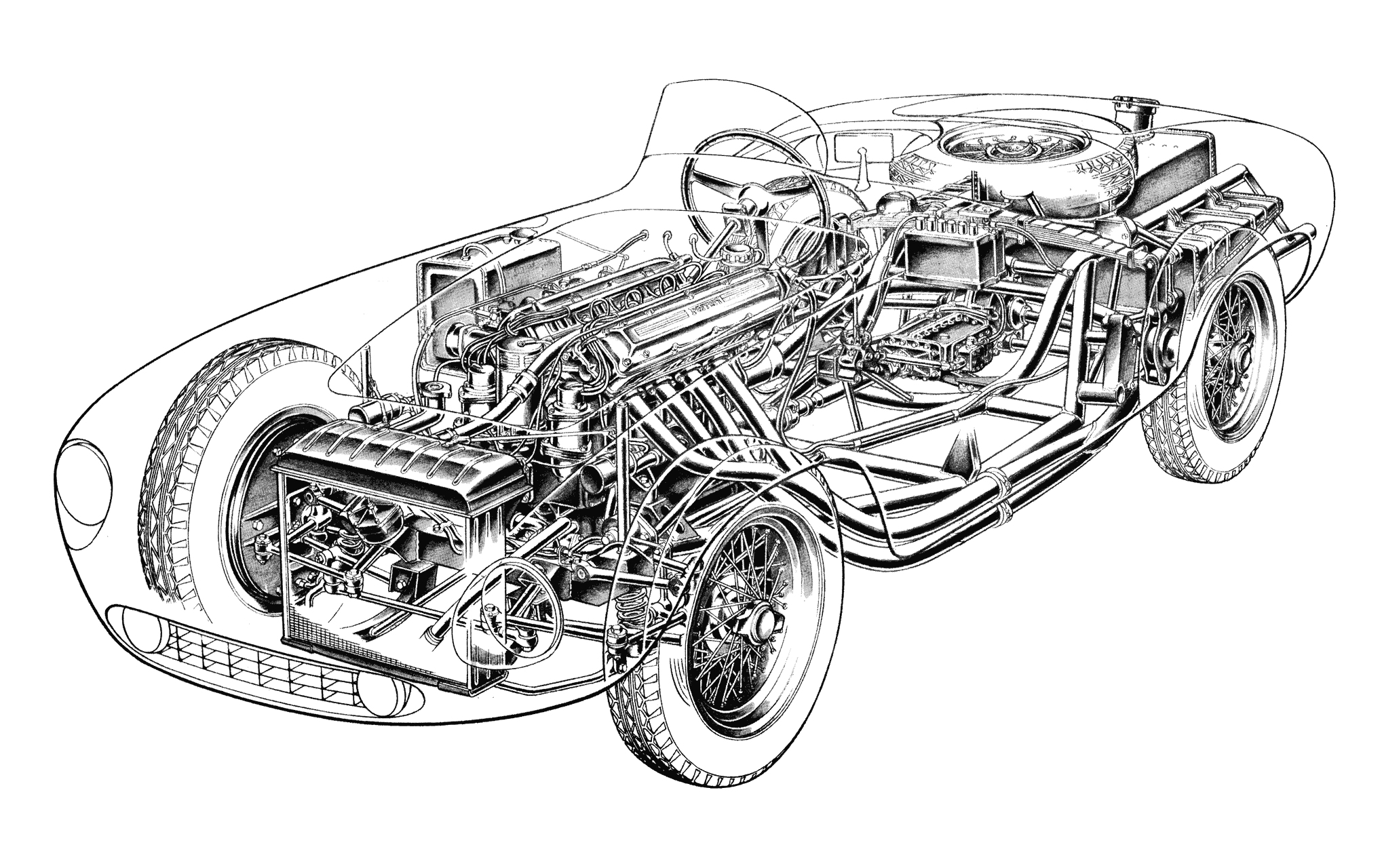

Ferrari’s early angled-tube chassis experiments were refined into a smoothly contoured structural base for the Monza. Two oval-section tubes were the main members, cross-linked and integrated into the body by many smaller steel tubes. Rear suspension was de Dion, its 2.5-inch steel axle tube curving behind the differential and connecting the fabricated hubs. At the tube center a ball carried a square bronze block vertically between steel plates in the back of the differential casing to locate the tube laterally. In the mode made good by Aurelio Lampredi, two parallel radius arms on each side guided the tube and absorbed braking torque. Since each set of arms forms a parallelogram, vertical movement of one end of the tube produced no twisting moment between hubs so floating mountings are avoided. Rubber bushings were used at the chassis connections, while the axle ends of the arms had ball joints.

Frame-mounted above the axle casing, a transverse-leaf spring was connected to the hubs by long drop shackles. Rubber buffers acting against the de Dion tube limited jounce while dampers were Houdaille vane type. The early Monza front suspensions also used transverse leaf springs, as was then current on the GP cars. After Barcelona in 1954 proved the superiority of a coil layout on the Squalo Ferrari a switch to coils was made on the parallel-wishbone suspension of all Maranello models.

Front-suspension geometry gave a roll center near ground level. Thanks to an anti-roll bar more of the overturning couple was resisted by the front wheels, producing heavy understeer and leaving the rear wheels free to put power on the road. This, plus the limited-slip differential, frame-mounted final-drive gears and low rear unsprung weight gave the Monza excellent traction.

At the front of the chassis, tapered steering arms extended forward from forged stub axles and were connected by a three-piece track rod. A forward Pitman arm transferred motion from the worm-and-wheel steering box, balanced by a slave arm on the left-hand side. The long-revered Ackermann steering principle was judged inappropriate here, a trend also affecting other high-performance cars. Three universal joints carried the steering column sharply around the protruding carburetors.

Racing experience was revealed by the disposition of the electrical equipment, which was readily accessible in the event of a petty breakdown. The battery was above the gearbox between the seats while all junction boxes and relays were on a single panel under the cowl on the passenger side. Instrumentation included tachometer, ammeter, oil pressure and oil and water temperatures. A hand-brake lever was suspended on the right of the cockpit, applying the rear brakes through a cable system.

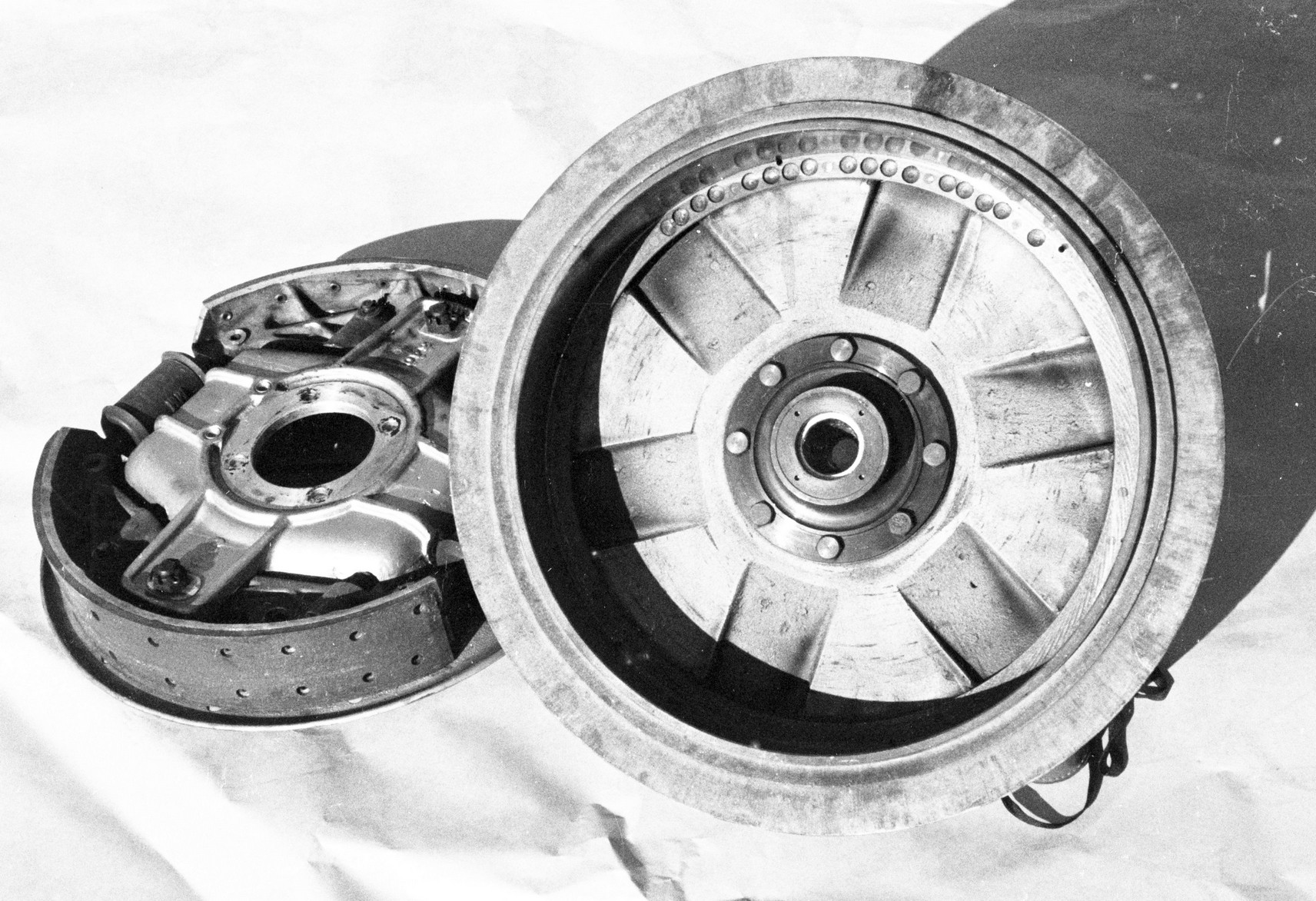

The Monza’s drum brakes were of Lampredi’s distinctive design with a central guide for each shoe to balance the servo effect and wear. Two double-acting cylinders per wheel applied force equally to all four shoe ends. Radial ducts in the drum faces acted as centrifugal extractors to draw cooling air into the deeply finned drums.

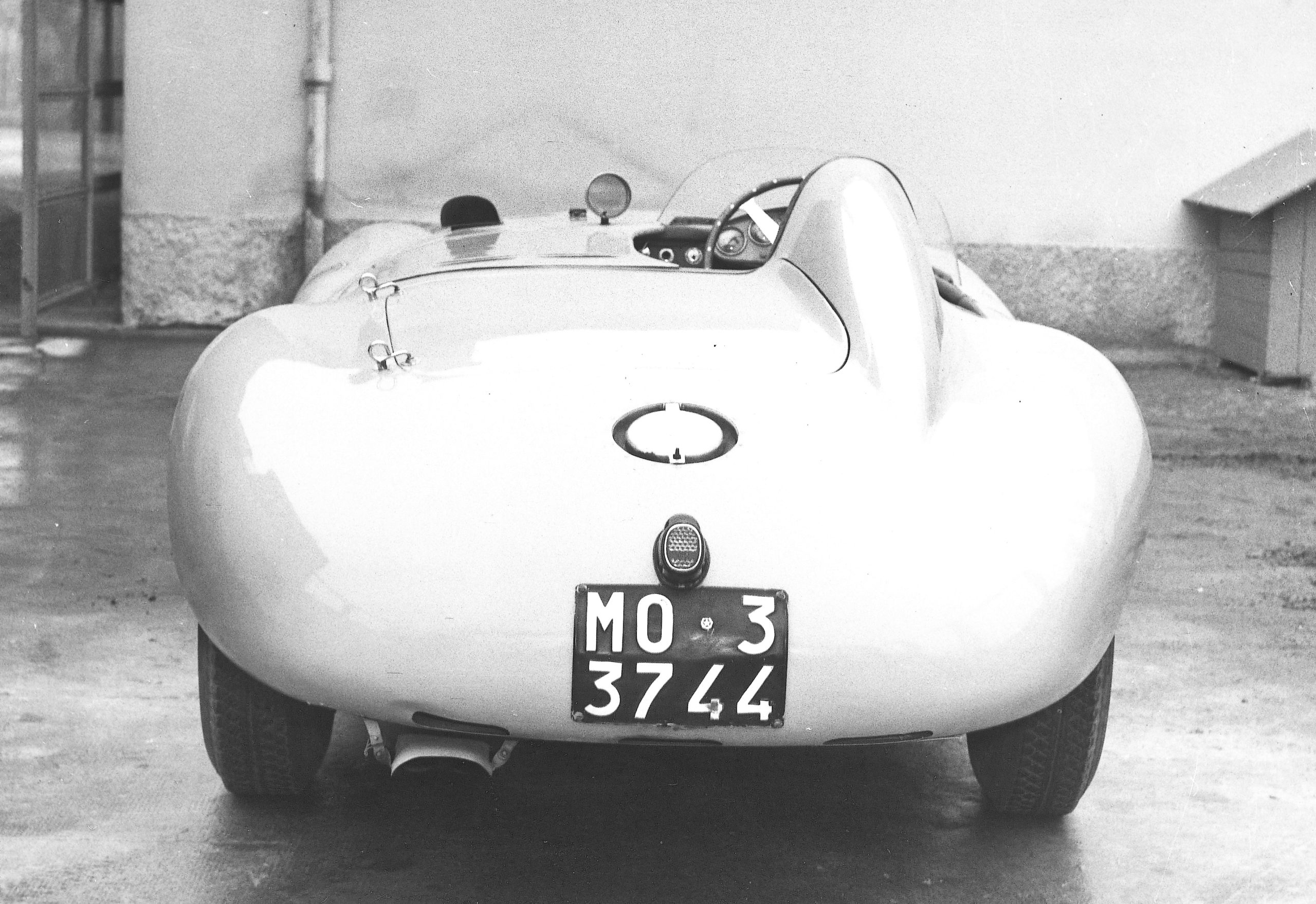

The final shape of the Monza and its smaller sister the Mondial was based on a concept by Enzo’s son Alfredo “Dino” Ferrari. Executed by Sergio Scaglietti’s coachworks, its splendidly aggressive lines were penetrative but susceptible to lift, especially at the rear. In combination with the Monza’s heavy understeer this promoted treacherous handling at the limit that caught out some of the world’s best drivers.

Versatile Briton Ken Wharton was killed in a Monza crash in New Zealand early in 1957. In Sweden in 1955 the experienced Paul Frère found his Monza “like driving without suspension. There was considerable friction in the steering, the brakes were very hard and not very efficient and the understeer was monstrous.” When qualifying Frère understeered off the road, luckily escaping with a broken leg. In 1960 the Belgian drove a Monza as a practice car for the Targa Florio and found that “its behavior was completely unpredictable.” He went off the road twice and “was not the only one to find himself in difficulty” with the 750 Monza.

Less fortunate was Italian star Alberto Ascari, who was killed at Monza in a 750 that overturned at the corner that now bears his name. At the time of Alberto’s death no one dared suggest that the great master had made a mistake. Rather it was hypothesized either that his tie had flown in his face—he was testing in street clothes—that a strong crosswind had hit, that he swerved to miss a workman crossing the road, that he suffered a blackout following his accident the weekend before, that a wheel rim dug into the asphalt or that he was simply fated to die then and there. It’s most likely however that the Monza’s deep understeer ended in a snap oversteer that not even Ascari could control.

When driven with respect for its limits the 750 Monza proved a lively competitor, its engine’s rich torque range a boon to its drivers. There was no denying its lack of cylinders, however. “In third gear there is a permanent vibration at all revs which makes you feel as if you have spent the day sitting on a steam hammer,” wrote Hans Tanner, who also found “that at about 3,500 rpm it sounds like a boiler factory working overtime.” “Although it is not smooth,” reported John Bolster, “the engine has an effortless feeling about it that has always been a feature of big four-cylinder units.”

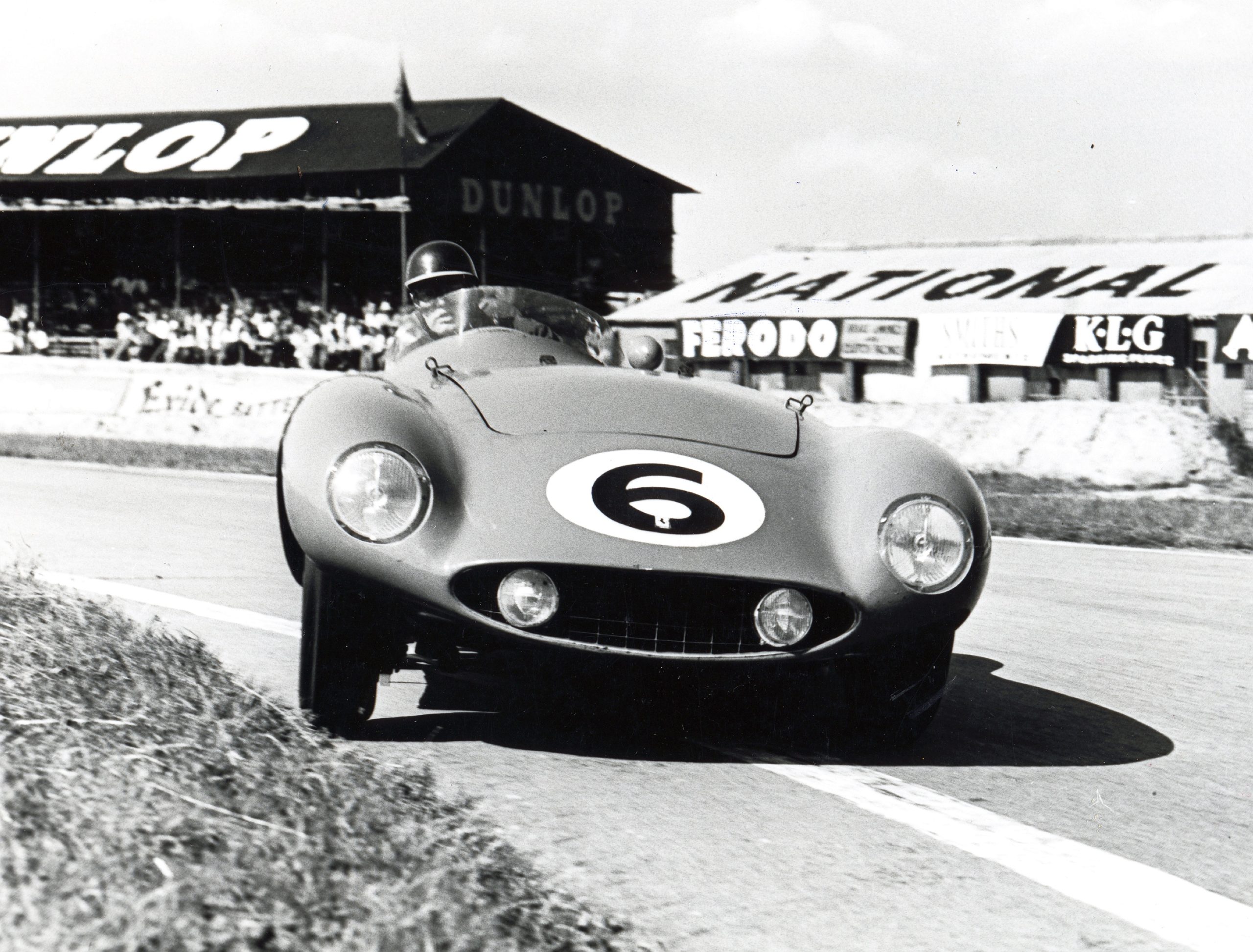

After the Ferrari’s successful debut at Monza, 1954 saw wins for Gonzalez on Portugal’s Monsanto circuit on July 25 and on August 8 at Senigallia on the Adriatic in the hands of Maglioli. September 11th brought Hawthorn and Trintignant outright victory in the demanding Tourist Trophy driving already-veteran chassis 0440M. This would go down in Ferrari’s history book as the model’s finest achievement.

Spain’s Alfonso “Fon” de Portago failed to finish in November’s Carrera Panamericana but in December won the Bahamas Cup race and placed second in two other events. Further successes came in minor events at Agadir and Dakar in February and March of 1955. An entry by Allen Guiberson at Sebring in March for Phil Hill and Carroll Shelby saw both the Ferrari and a Hawthorn/Walters Jaguar D-Type credited with 182 laps in twelve hours. The final verdict in this contested result saw the honors go to the English car. Luigi Chinetti’s entry for Harry Schell and Piero Taruffi placed fifth.

An important East-Coast customer was George Tilp, whose stable soon housed a 750 Monza. As the ’55 season matured so did the population of Monzas in the hands of privateers. In California Sterling Edwards decided to stop building his own cars and bought a Monza with which he won at Bakersfield in May ahead of John von Neumann in a similar car. An early adopter was France’s Louis Rosier, as was Swiss racer and hill-climber Willie Daetwyler. In Belgium Jacques Swaters added 750 Monzas to his Equipe National Belge.

An important race for the Ferrari 750’s namesake was the 1,000 kilometers of Supercortemaggiore at Monza on May 5th 1955. Mike Hawthorn and Umberto Maglioli carried Ferrari’s flag against Maserati’s new six-cylinder 300S in the hands of Jean Behra and Luigi Musso. The result, at an average speed of 110 mph, was victory for the Maserati only 7.3 seconds ahead of the Ferrari. Monzas were also fourth and fifth, the battle between the Modena racing-car makers now being fully engaged.

Frustrating Maserati, however, the World Sports-car Championship went to Ferrari’s Monza and its derivatives in that series from 1954 to 1957 with the exception of 1955, when Mercedes threw a last-minute “Hail Mary” pass to take the trophy in Sicily. In 1958 the classic V-12 would make a comeback.

The George Tilp Monza was still in good fettle on the 4th of July, 1955 at Beverly Airport’s SCCA National, which was won by Phil Hill in the white machine. Hill also prevailed at Elkhart Lake on September 11th. When in California Hill drove the Monza of John von Neumann. Masten Gregory was racing his Monza in Europe, winning at Monsanto in July. In 1956 a newcomer named Carroll Shelby made his mark with a Monza from the Richard Hall stable. Hall’s brother Jim started racing the Monza in 1957.

The last of the 31 Monzas built battled it out with others in minor races in America into the 1960s. Other Ferrari engineers gave Lampredi’s creation more life with still-larger four-cylinder engines until the concept of the four reached its limit. But the 750 Monza remains well-remembered for the first of the Dino Ferrari body designs and “sounding like a boiler factory working overtime.”