The Sunbeam Tiger is a car well-known to enthusiasts. European cars with powerful American V8s are intriguing. Most of the time these Euro-American hybrids came with high-end, sexy bodies to house their muscular engines, such as the Facel Vega, Iso Rivolta and Griffo, and of course the Shelby Cobra. The Sunbeam Tiger had the muscle of an American V8, but the pedestrian styling of a well-known inexpensive 4-cylinder British car. Although attractive, the Sunbeam Alpine Series 1 (introduced in 1959) was only slightly different in appearance from the Tiger (the Alpine Series IV by 1964). The Rootes Group that manufactured the Sunbeam wanted to promote the new Tiger by putting the car on the world racing stage, and in 1964 there was no larger stage than the 24 Hours of Le Mans. A racecar based on the new Tiger would have to be designed, built and tested in just a few months. What could go wrong with that plan?

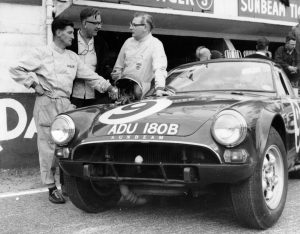

Photo: David Gooley

Sunbeam Alpines had enjoyed some racing successes, but with the V8 Tiger, the Rootes Group was entering uncharted territory with a large displacement, prototype class car. Brian Lister, the builder of many successful Jaguar racecars, among others, was chosen to build a prototype test mule, plus two more cars to be used as works cars for the race. Being in the prototype class, Lister wanted to build a lightweight custom racecar chassis with a somewhat stock-in-appearance body, a proven formula Lister had done for other manufactures many times. Rootes said no to a custom chassis, directing Lister instead to build the car with the Alpine’s monocoque, which had a short wheelbase derived from the Hillman Husky—not exactly the preferred DNA of a racecar. Rootes wanted the car to be more like the stock Tiger for marketing and publicity purposes. This decision, for better or worse, would shape the course of the design and, ultimately, the performance characteristics of the car.

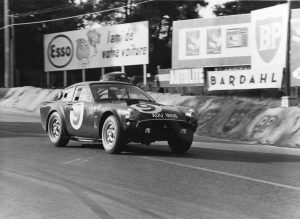

The body Lister crafted was a fastback coupe. Interesting was the fact that one of the more successful previous Sunbeam racing accomplishments was in a fastback coupe produced by Harrington, when it won the 1961 Index of Thermal Efficiency at La Sarthe. Working within the perimeters of the Alpine/Tiger design, Lister used the stock nose and floor pan, with flared front fenders. However, the similarity with the stock Tiger ends there. A sleek fastback roof descended back to a wide Kamm-tail with flared quarter panels designed to accommodate 15-inch wheels. The distinctive tailfins were nowhere to be found. Rootes vetoed the use of a custom chassis so it would look more like the stock Tiger, but in the end, the Lister body was so unique it was hard to tell what kind of car it was on the track. To make matters worse, instead of reducing weight, the car was approximately 20 percent heavier than a stock Tiger, and one of the heaviest cars in its class when it ran at Le Mans in 1964.

The man overseeing the project was Norman Garrad, the father of Ian Garrad (Rootes’ West Coast manager, who had pitched the idea for the Tiger to Lord Rootes, resulting in production starting in the Spring of 1964). He seemed the perfect man for the job, but he left the Competition Department in February 1964. Marcus Chambers was subsequently hired as the new head of the Competition Department that same month. Experienced and successful from his years at BMC, he was excited about his new position with Rootes…that is until he saw the Le Mans racecar project. According to Chambers, “The whole project was a disaster about to happen from the minute old Alpines finished the preceding 24-hour race.” He also thought the dated Alpine-based chassis and short testing period before the cars hit the track at Le Mans were a “terrible handicap on the whole project.”

The engine is the very heart of a performance car, and the Ford 260-cubic-inch V8 that was going in the Tiger production car was considered rugged and reliable. Wanting the very best engines for the racecar project, the engines were purchased from the foremost authority on Ford racing engines, Carroll Shelby. Shelby had created a V8 Alpine prototype for Rootes in 1963 that would prove the viability of a production street car that would go on to become the Tiger in 1964. It was a tight fit, as Shelby explained, “I think that if the figure of speech about the shoehorn ever applied to anything, it surely did to the tight squeak in getting that 260 Ford mill into the Sunbeam engine compartment. There was a place for everything and a space for everything, but positively not an inch to spare.”

The engines ordered from Shelby were received several weeks late, leaving Rootes with very little time for thorough testing. Mike Parkes, who previously worked for Rootes but was working for Ferrari at the time, offered to take the newly assembled Lister Tiger Test Mule out for a few laps during the April Le Mans test session. Shortly thereafter, he politely informed the Rootes Group that they had a lot of work to do if the car was going to be even slightly competitive. Further testing revealed that the engine ran hot and had low oil pressure from what was suspected to be an oil surge in the sump. Axle tramp was also reported. Parkes and another tester, Keith Ballisat, both reported that the car’s road holding ability was poor and the brakes were even worse. Parkes had lapped in 4m26.4s with the Sunbeam compared to his 3m47.1s driving his Ferrari. As a result, adjustments were made to the car by the Rootes team, which included a better front anti-roll bar, moving the rear Panhard rod and tinkering with shock and spring rates. All these tweaks helped, but more testing was needed. Unfortunately, they were out of time.

Rootes entered two Lister-bodied cars in the 1964 24 Hours of Le Mans. The #8 car was registered as ADU 197B and driven by Keith Ballisat and Claude Dubois. The #9 car featured here was registered as ADU 180B and driven by Peter Procter and Jimmy Blumer. Both cars were set up like the Mule test car, with 260 Ford V8s. Fuel was fed through two four-barrel 460cfm Carter carburetors.

Marcus Chambers had deep reservations about the cars appearing in the race. Chambers was torn between pulling the cars out of the race completely, or letting them race as planned. After some soul searching, he decided it was better to gain the publicity from running the cars in the race than withdrawing and having to explain why he thought failure was imminent. Failure did come, though, as both cars were unable to finish the race. ADU 179B broke a piston only three hours into the race and had to retire. ADU 180B fared better but suffered a broken crank in the ninth hour after completing 123 laps with an average speed of 107 mph. It was clocked at 162.2 mph on the Mulsanne and made it up to 18th position during the last hour before it retired. Peter Procter was at the wheel of AU 180B when the engine blew in spectacular fashion just as the he came up on the pit area, detonating in a flash of fire and scatttering parts down into the suspension, which caused the steering to lock up completely. Hitting the brakes hard, he drifted over the demarcation line between the pit lane and the track, and headed right for the pits at a high rate of speed. He finally came to a stop rubbing the side of the car against the pit counter. The pit marshal ran over to Procter and told him he was in trouble for crossing the line and to move the car at once. Procter said OK, telling the official to steer while he pushed. The official reported that the car would not steer. Procter replied, “That’s why I parked it up against the fucking pit counter!”

Shelby shared the blame for the engine failures and reportedly refunded Rootes for the power plants. According to Chambers, “Brian Lister went off and got drunk as he was so depressed about the whole thing and felt that his reputation as a racecar builder, which was of the highest, had been severely compromised by having to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

After Le Mans, ADU 180B went back to the Rootes Group and was lent to Bernard Unett, one of the development engineers involved in the Le Mans project. Unett made changes to the car that included a five-link rear end and upgraded 289 engine fitted with four Weber 48 IDA carburetors. Unett successfully campaigned the car in the Autosport Championship series in England in 1965 entering over 20 races, taking 11 wins and nine 2nd-place finishes. It is believed Unett raced the car during part of the 1966 Autosport season, with its last race at Brands Hatch in March, where it came in finishing a close 2nd to a Lotus Elan. It was then stripped of its drivetrain, suspension and various body panels at Alan Fraser Racing in Kent, England. The parts were used to build the “Monster” Tiger racecar. ADU 180B languished on the Fraser estate until 1971 when Ted Walker found, rescued, and restored it over the next few years. It was subsequently sold to another collector, Ken Dalziel, who performed more restoration work and got the car back on the track for the first time in 13 years. In 1979, Chris Guys (the current owner of the Monster Tiger) purchased ADU 180B and shipped it to Southern California where it was entered in various historic race events during the early 1980s, including the Monterey Historic Automobile Races.

In November 1987, it changed hands again when it was sold to Ron Bennett at the Rick Cole Auction in Palm Springs, California. After only about a month of ownership, ADU 180B had an engine fire on start up. Bennett had planned to convert the car into a street car, but decided, after only about a month of ownership, to sell it to Lister car collector Syd Silverman who had also bid on the car at the Rick Cole Auction. Silverman entered the car in many SVRA vintage races with several different drivers, up until it was sold at the 2001 RM Monterey Sports Car Auction to its present owner Darrell Mountjoy.

Darrell was excited to drive the car after he purchased it at the auction…who wouldn’t want to start enjoying such a rare and historic car right away? He could not wait to get behind the wheel. He had a friend drive it from the auction. Unfortunately, on the way home the car was involved in an accident. He had planned on doing some work to the car, but after the car’s off-road adventure, the decision was made to have the car completely restored from top to bottom. An eight-month restoration by Alcala Restorations returned the car to its original form and livery. Over the years of its life, modifications had been made to the car, so quarter panel flares were corrected and various modern upgrades were removed and replaced with authentic parts. Every effort was made to retain as many of the original parts as possible with a great amount of attention to detail during the restoration. The result is a beautifully restored and authentic car that looks at home on the track as much as it does in a concours.

I asked Darrell how the car drove and what the handling characteristics were like, having read about some of the steering issues during my research. He told me that Syd Silverman’s mechanic, John Harden, said, “It wants to swap ends on you at 150 mph.” Darrell said he had not driven it that fast, but it felt like it had four-wheel steering. Darrell was determined to find out what was causing this effect, going so far as to make a scale model of the rear axle and suspension system. By manipulating the different parts on the scale model, he could see how all the different parts interacted with each other. These tests revealed that the rear leaf spring blocks were installed incorrectly and were binding up, causing the rear end to move. With the problem corrected, Darrell says the car now handles great.

Darrell took the car back to Europe in 2002 and participated in the Goodwood Revival, as well as the inaugural Le Mans Classic race in France, driving with Peter Procter on both occasions. The car has run in many West Coast historic races and been displayed at car shows as well. The car is always well received and a crowd pleaser.

Driving Impressions

Approaching the Lister Tiger it looks like a small package on steroids… a little bulbous here, a little bulbous there. Get in, press the starter button and this little monster comes alive. Its short wheelbase and small block Ford engine make it an exciting drive on the track.

With the rear suspension corrected and its weight bias at a nearly ideal 50/50, as well as its corner weights being nearly spot-on, the car is now predictable approaching and exiting turns.

Presently it rolls Dunlop Racing CR 65 bias-ply tires, like those originally fitted for Le Mans in 1964. Some may say it is a bit of a disadvantage on the track today, but that is what the car originally ran with and if one wants to experience the car in its true form then these are the tires of choice. Hoosiers or Goodyears may have a lot more rubber on the road, but those modern tires are not what the car was originally designed to use and will compromise the driving “experience.”

With the Dunlops being bias tires, the car’s driving line will be different on track from those running radials, and the experience will be totally different. Simply put, a completely different driving style is required, but it’s one that is endearing. Some have referred to it as “Slide Time.” Coming into a turn, you turn the steering wheel a little, lift the throttle a little and allow the tail to come out to get your desired slip angle. Then you steer with your right foot and counter-steer with the steering wheel. You kiss the apex as you squeeze in the throttle and it’s simply exhilarating. The car is so compliant.

All that being said, the car is so much fun to drive at speed. It is both predictable and reliable. The transmission gears are well spaced, and with its 3.76 Salisbury differential gears it is well suited for most of the tracks here in the United States. At speed, this car was clocked at 162 mph on the Mulsanne Straight in 1964. Despite its lack of aerodynamics, which later cars incorporated, this car performs intriguingly well today in its original form.

Brian Lister, with Ken Hazelwood as the project engineer for this and its sister racecar, incorporated the same Girling brake calipers front and rear as Shelby American Inc. used on its comp cars and Daytona Coupes. Needless to say, the car stops well.

We mustn’t forget the Weber carburetors, which perform wonderfully on the car. For the Le Mans effort in 1964, the engines were supplied with twin Carter four-barrel induction. These were not the best choice for a Grand Prix racing circuit and were swapped out early during the 1965 Autosport Championship season for four two-barrel Weber 48-IDAs. Squeeze the throttle down and listen to them come alive as the car roars. It’s a sound like nothing else.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Unitary Steel

Wheel Base: 2200 millimeters

Track: Front: 1320 millimeters, Rear: 1330 millimeters

Weight: 1146 kilograms / 2521 pounds

Fuel Capacity: 137 liters

Engine: Ford pushrod V8

Displacement: 4,737-cc

Bore / Stroke: 101.60 millimeters x 73 millimeters

Power: 330 bhp @ 6,000rpm

Carburetion: Four Weber 2V 48 IDAs

Gearbox: Borg Warner T-10

Differential: Salisbury LSD

Suspension: Front: Coil spring with pressed steel wishbones, Rear: Leaf spring, 4-Link live axle with Watts linkage

Dampers: Koni Adjustable

Steering: Rack and Pinion

Brakes: Girling Discs

Wheels: Dunlop Alloy, 15x 6

Tires: Dunlop Racing CR 65, Front: 6.00L-15, Rear: 6.50L-15

RESOURCES

ACCUS FIA/USA, Historical Technical Passport

FIA Class: GTP F

Burdette Martin Jr., ACCUS Historic Vehicle section

Jeremy Hall, ACCUS Historic Vehicle Section

Personal diary notes: Marcus Chambers, Manager,

Competitions Department, Rootes Group