Boy Meets Car, Loses Car, Finds Car

By Steve Smith | Photographs as credited

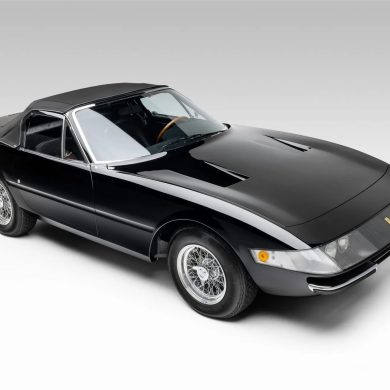

Every car guy has the automotive equivalent of the fisherman’s “the one that got away” story (“It was this big! Really!”). The car of a lifetime…loved and lost. Some car guys even have two such tales. Like my friend Brock Yates. He once had the opportunity to buy one of the world-famous D-Type Jaguars (similar to ones that won Le Mans; only a few dozen were ever built). The owner, Bill Sadler, wanted to sell it to raise the money to build his own sports-racing car. He offered it to Brock for a mere $2,000—about a third of its value then—but this was in the mid-1950s, early in Brock’s stellar career, before he was famous…much less rich…so he passed. The car is worth about $4 million today. Another time, Brock, now more affluent (this was in the early 1970s), bought a Ferrari Lusso, possibly the most beautiful Ferrari ever made, for $6,000. Brock was nervous about using such a treasure as a daily driver (a gas station attendant once accidentally broke the $400 gas cap), and sold it for $6,000 a year after he bought it. He hadn’t lost a dime and thought he’d cheated the hang-man, used-car-wise. A Lusso like Brock’s would fetch at least ten times that today.

Other car guys all seem to have owned (or could have owned) an incredible piece of machinery—for a song—that today sits in a museum or under the gavel of some gibberish-spewing auctioneer. My own story is about one of the first three Chevrolet Corvettes ever to compete in the famous 24-hour race at Le Mans, France, in 1960. (Actually, there were four Vettes lined up for the start of the race that year, but the fourth car is not germane here.) The trio of white Corvettes with broad blue racing stripes was entered by Briggs Swift Cunningham, a millionaire sportsman (he was heir to the Armour Star meat-packing fortune) who had spent a million dollars—back when a million dollars was a boat-load of money—trying to win Le Mans with an American car.

Briggs’ first attempt was in 1949, with a hot-rod built by Bill Frick (inventor of the Studillac; a Studebaker with a Cadillac engine). It was turned down flat by the organizers; an American hot-rod was considered too déclassé for the chi-chi event. The next year, a sympathetic General Motors offered Briggs two gigantic Cadillac Coupe DeVille luxury cars for the race. These were deemed acceptable by the organizers, so Briggs entered one in more or less stock trim (it even had air-conditioning), but stripped the 2-door body off the other and replaced it with a boxy roadster body as a nod toward improving its barn-door aerodynamics. The French dubbed it “Le Monstre.” It didn’t fare well. Briggs drove it into a sandbank and lost a lot of time digging it out. It finished 11th. The stock Coupe DeVille did better; finishing 10th, which was considered outstanding for a big, ungainly American touring car.

Briggs kept at it for the remainder of the decade. He even built a factory in West Palm Beach, Florida, to manufacture his own car, the Cunningham C-series (a few dozen were built; they’re worth a fortune—each—today). The best he ever managed were back-to-back third-place finishes (in ‘53 and ’54) with Chrysler-powered Cunninghams. Coincidentally, in mid-decade (1953), Chevrolet brought out America’s first modern sports car, the Corvette. The first examples weren’t very racy, with an anemic 6-cylinder engine (“Blue Flame Six” sounds like a kitchen appliance), a loosey-goosey automatic transmission (derided as a “glue-pot twirler” by the cognoscenti) and inadequate drum brakes. By the late 1950s, however, a Russian émigré, Chevrolet engineer Zora Arkus-Duntov, had developed the Corvette into a decent road-racing competitor, with a powerful fuel-injected V8 engine, a 4-speed stick shift, and gigantic (although still marginal) drum brakes.

By then, Briggs had all but abandoned the idea of winning Le Mans. He had closed the factory in Florida, bought a Jaguar distributorship, and was racing almost everything but American iron: Jaguars, Maseratis, Listers, a Porsche, an OSCA, a Stanguellini…everything except Ferraris (some bad blood there)…and with almost every great American driver active at the time (Sherwood Johnston, Phil Walters, Walt Hansgen, Bill Spear, John Fitch and my mentor, Denise McCluggage, who first introduced me to Briggs). Then Chevrolet’s Zora Duntov talked Briggs into entering three Corvettes in the 1960 24-hour…and the die was cast. Once again, the dream was alive! Cunningham sent a minion over to Don Allen Chevrolet near Columbus Circle in Manhattan to buy three 1960 Corvettes for the “friendly” price of $3,910.08 each, with every racing or heavy-duty option offered by the factory, including a 283-cubic-inch, fuel-injected engine ($484.20 extra); sintered-metallic brake linings and faster steering ($333.60), a close-ratio 4-speed transmission ($188.30) and a limited-slip differential ($43.05). Stiffer suspension components and a 37-gallon gas tank (the largest permissible under the Le Mans rules) would be added later.

The cars were turned over to Briggs’ longtime chief mechanic, Alfred Momo (who had flown in WW I with the poet Gabrielle D’Annunzio when they dropped peace leaflets over Rome) for race preparation. Briggs’ cars were always as well turned-out as Futurama show pieces: no detail was too small, no part left unexamined, nothing left to chance. Years of trying to win Le Mans had left Briggs with a healthy fear of electrical failure. So, as just one example of meticulous preparation, Momo replaced the factory fuel pump with not merely one heavy-duty mechanical pump, but two additional electrical pumps (operated by dashboard switches). The stock tachometer was superseded by a huge Jones-Motrola mechanical tach (with a telltale needle so Briggs could see if any of his drivers exceeded his strict engine rev limits). The dash was painted matte-black so nighttime reflections wouldn’t distract the driver. The puny gas-tank cap was replaced with a massive aircraft fuel-filler and relocated to a cove cut into the middle of the rear window. The unsupportive seats were replaced with snug-fitting bucket seats from a WW II-era DC-3 to prevent the driver from sliding around in the corners. The ignition coil and 12-volt battery were doubled, like pairs of animals on Noah’s Ark (and for the same reason: survival).

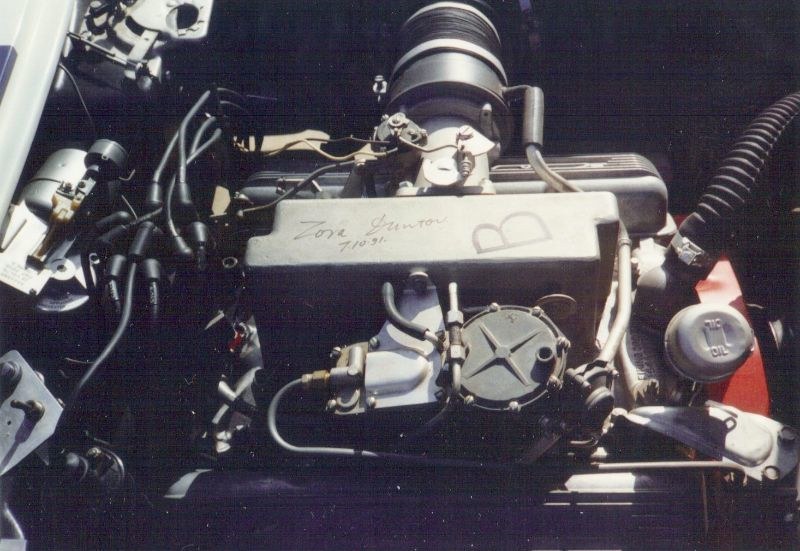

The one thing Momo didn’t work his magic on (he was said to be able to increase the power of any motor just by lifting the hood and passing his hands over it) was the engine. Momo had had vast experience not only making engines more powerful, but also longer-lasting, as endurance racing is more about reliability than speed. But Duntov had promised Briggs a truckload of engines race-prepared in GM’s fabled Tech Center, with next year’s fuel-injection system and cylinder heads (aluminum instead of cast-iron, to save precious weight). Momo didn’t take Duntov’s word for it, and disassembled one of the engines to see the modifications for himself. Everything looked good to him…except for one detail. The bearing that held the distributor shaft in place was a plain bushing bearing. Momo wanted to replace it with a more durable needle bearing. Duntov was insulted. “I haf tested on dynamometer twenty-fife hours,” he said in his thick Russian accent (he pronounced Corvette, “Cor-WAAT”). “Not fail.” The stock engines were removed and Duntov’s fully tweaked engines (although with the stock cast-iron cylinder heads) were installed.

Le Mans wasn’t until June, but Cunningham and Momo wanted some race experience beforehand, so they took two of the cars to Sebring in March for the 12-hour race there on the 26th. (The third car was actually present, in street trim—it hadn’t yet been race-prepared—driven by Sports Cars Illustrated’s Steve Wilder from New York and back again after the race). Fortune did not smile on the Cunningham team that day, but they learned a valuable lesson. The #1 car, driven by Briggs and John Fitch, broke a wheel in the Webster Turns, flipped over and was out after only 27 laps (the race was to last another 169 laps). The other car, #2, driven by Corvette specialists Dr. Dick Thompson (“The Flying Dentist”) and good ol’ boy Freddie Windridge, lasted until lap 41 before its engine expired. This engine was sent to Duntov for analysis. The #1 car’s accident had occurred because the jury-rigged wheel hubs hadn’t been strong enough. Momo replaced the front hubs and rear half-shafts with stronger units. The Indy-style Halibrand magnesium wheels were held on by knock-off spinners (instead of lug bolts), so the wheels and tires could be changed faster during pit stops, something else Briggs had learned about endurance racing.

The #2 car’s engine came back from General Motors…rebuilt, but still with a bushing distributor bearing, Momo noticed. Dubious, he and Briggs decided to test the car for 24 hours in a private session at Bridgehampton (a long, willowy race track on the Eastern end of Long Island that bore little resemblance to the circuit in France where the 24-hour race would actually be held). I was visiting a friend nearby when I heard the distinctive thump of an American V8 at racing speeds, so I came over to have a look. The Corvette team experienced various niggling problems, but by and large the test went off without a hitch, with Briggs, fellow car-dealer Bob Grossman and John Fitch sharing the driving.

The organizers of Le Mans held their own test day for all interested parties in April of every year, so what would become the #2 Corvette in the race (the last one bought—the only one that had not raced at Sebring—by now fully race-prepared) was sent over to the famous Sarthe circuit to see what kind of laptimes it could turn…and what problems might crop up. One engine failed (a bent pushrod, it was said), but by-and-large, as at Bridgehampton, things went well. The timing sheets show that Dick Thompson turned respectable laps in the 112-mph range (4 minutes, 28.3 seconds of the 8.36-mile course), with a top speed of 152 mph on the three-and-a-half-mile long Mulsanne straightaway. Things were finally looking good for big, heavy (2,975 lbs.) American iron. The car returned to these shores.

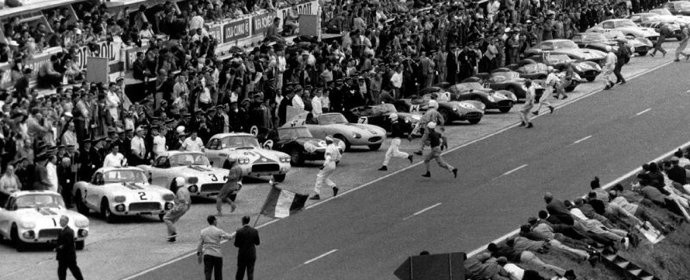

All three cars were sent back to France on the Queen Elizabeth (registered as John Fitch’s “luggage”) and driven from Le Havre to Le Mans under their own steam. They lined up by displacement for the 4 P.M. start on June 25th; the cars with the biggest engines at the front. The Cunningham Corvettes occupied the first three spots. The drivers lined up on the other side of the track, and when the chief steward signaled the start, they dashed across the track, leaped into their cars (hopefully fastening their seatbelts; the ones in Briggs’ cars were fighter-aircraft quality, four inches wide), spun the ignition keys and joined the fray. Duntov had originally been assigned to co-drive the #1 car with Briggs, but wiser heads prevailed (Zora was one of the worst drivers I have ever had the misfortune of being in a car with) and he was replaced by the young Bill Kimberly…who though not untalented proved to be unlucky. After a couple of hours, just after Briggs turned over the car to Kimberly, a light rain started to fall, and Kimberly skidded off the slippery track at a very fast turn called White House and rolled the car over. As it came to rest, flames leaped out from under the hood. With the car seriously on fire, the disappointed driver scrambled out, unhurt, and walked “the longest mile” back to the pits.

The #2 car, in the hands of the Corvette experts, Thompson and Windridge, had been assigned the role of rabbit; to go as fast as possible, so as to sucker its competitors into trying to keep up, the idea being that the competition would burn itself out in the effort, no matter what happened to the rabbit (which would be sacrificed, if necessary). The #3 car, driven by old hands Fitch and Grossman, would pace itself, so as to be there at the finish, 24 lo-o-o-ong hours later. (The #1 car was basically insurance…or was until its accident). This is classic endurance-racing strategy…and it might have worked, too (the #3 car was as high as fourth in the middle of the night, a third of the way through the race), if…if only….

The #2 car lasted until noon the next day, only four hours from the end. It had been much delayed by a chance encounter with a sandbank (and subsequent repairs to its right front fender), and was in twenty-something place, when the engine let go with a loud bang as Windridge thundered past the pits (the same car had lost an engine in practice). Thompson later admitted to using the engine to slow the car after its brakes had started to fade. All eyes were now on the remaining #3 Fitch/Grossman car. It was holding its own and anticipating a top-ten finish, when it started overheating. Although no one knew it at the time, Alfred Momo had been right: the bushing bearing supporting the distributor shaft was wearing out (as Momo predicted it would), allowing the distributor to advance the spark several degrees, causing the engine to lose power and overheat.

Without tearing the engine apart, nobody could analyze the problem (it was initially reported as a blown head gasket…and compounded when a mechanic recklessly unscrewed the red-hot radiator cap), so the best they could do was add more water to the radiator when it boiled off as steam. The problem was that the rules of the race said you could only add water (or oil; the #2 car may have run out of the latter) every 25 laps. But the #3 car would start to overheat after only a few laps. What to do? Legend has it that Briggs, who had both a deep distrust of French cuisine and a love of ice cream, had parked a refrigerated ice cream truck behind the pits (along with 27 tons of spare parts and equipment) full of his favorite flavors. That much is true. In the fairytale version, Momo is seized by a beautiful vision, and starts packing ice cream around the engine every ten laps or so, and the #3 car charges back into the race dripping chocolate, vanilla, and (Briggs’ favorite) strawberry.

The truth is somewhat more mundane, but no less ingenious. Momo packed the dry ice from the ice cream truck into the engine compartment (the rules said no fluids), which would then last until they could legally add water to the radiator. To combat overheating, they slowed the car way down, but it had to maintain a minimum average speed or be disqualified. Lap times stretched threefold, to almost 15 minutes per lap. Somehow, Fitch and Grossman kept the #3 car alive and still in eighth place to the finish, albeit 285 miles (33 laps) behind the winning Ferrari. Not a very glorious end.

So, after ten years of trying, Briggs was back where he started: a massive effort ending in a mediocre result. Disgusted with Chevrolet (he would never race a GM car again, although he stayed very much in racing for years thereafter; he died in 2003 in his nineties), Briggs gave the three race-weary Corvettes to his old friend Bill Frick (who had built the hot-rod Briggs had tried to enter in 1949) for disposal. The remains of the #1 car, minus its charred fiberglass body, were said to have ended up in Florida with a Devin fiberglass replacement body, its provenance lost in the sands of time. The disappointing Duntov-prepared engines went back to GM and the original engines (which had come with the cars) were reinstalled (although Frick didn’t bother to reunite the correct engines with their original chassis). The #2 car was sold to a guy who worked for the National Zinc Company in New Jersey. The number #3 car went through seven oblivious owners before winding up in the hands of one Chip Miller, a certified car nut and the impresario of a Corvette swap meet in Carlisle, Pennsylvania (although “swap meet” doesn’t do it justice; it covers hundreds of acres, features thousands of vendors and tens of thousands of visitors each year). The #2 car also wound up at this gathering of the Corvette faithful in Carlisle, but that’s later in this saga of paradise found, paradise lost and paradise regained.

Part Two: Steve Smith

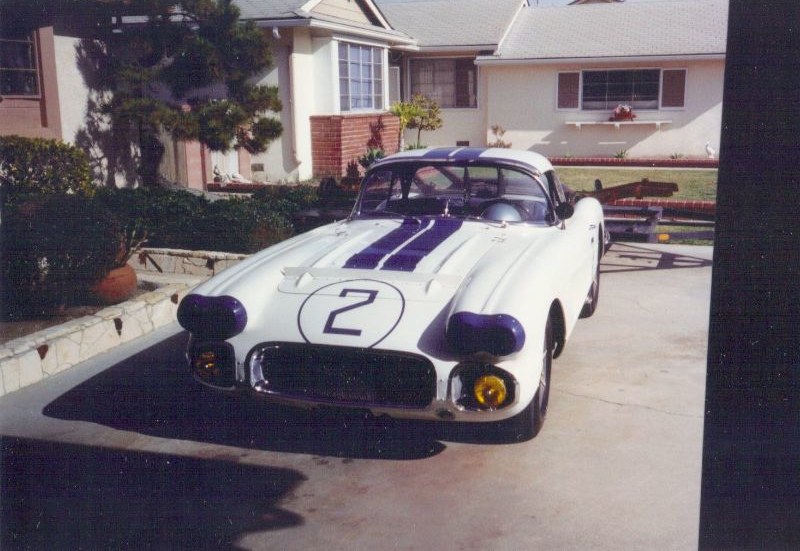

The National Zinc guy wasn’t happy with the #2 car. It wasn’t much of a street car, despite having an original, mildly-tuned V8 back under its hood. It still had its racing-number circles (which made it a cop magnet…even when it was standing still) and it still had a long, 3.55 rear-axle ratio (perfect for reaching its top speed, but making it nearly impossible to get a smooth start on a hill). Its original mufflers had been reinstalled, but it was still noisy and rattled and clunked like the old race-car it was. So he (the Zinc guy; I forget his name) put it up for sale…about the time I was preparing to leave New York City for California (in June of 1961), where I had a job with the publishers of Road & Track. For me, it was a choice between this clapped-out Vette or a very clean 1958 Porsche Carrera coupe. I decided against the Porsche because a) its highly-stressed—and highly expensive—roller-bearing crankshaft was prone to snap from a cold start, and b) the labor charge for changing its impossible-to-reach spark plugs (it had only four cylinders but eight spark plugs) was $600…and the platinum-tipped plugs themselves were extra. So I gave the National Zinc guy $3,800 in cash (and let him stay in my $96.42-a-month apartment in Greenwich Village until my unanticipated return a year or so later) and prepared to drive the ex-race car 3,000 miles—including much of the old Route 66—to California. (Honk if you’ve read Kerouac).

Before I left, I took it to Thompson Raceway, a road course in Northeastern Connecticut that I was familiar with, to see what she could do. What she could not do was stop. I didn’t know until much later—after I got to California—that the brakes were shot. The brake linings had been mostly worn away, and the friction surface was metal-to-metal…not conducive to short stopping distances. In my naiveté, I simply thought the massive pedal pressure necessary was because it was, after all, a race car (Phil Hill weight-trained when he was driving drum-braked Ferraris; he claimed the pedal pressure exceeded his own body weight). The beast (I took to calling her “Beastie” after this) could be brought to a halt, with much screeching and shuddering, only if I practically stood on the brakes with both feet.

The trip to California was my first cross-country trek. It took five days. After the second day, I was aching with pain. My right shoulder was killing me, and I spent an hour every night thereafter at each motel’s poolside working out the kinks. My butt was also sore. I could not imagine how Mssrs. Thompson and Windridge had managed to suffer the thinly-padded DC-3 seats. There was nothing anatomical about them: they were dead flat on the bottom and half-round on the top (not the shape of either my back or my butt). The stock steering wheel had been replaced by an Indy-type wheel, covered in rubber that got sticky within an hour. The brake pedal was hard as iron, but the clutch was almost as bad: the return spring was so strong that it would throw your knee back into your chest the instant you eased up on the pedal. I understood now why the National Zinc guy had wanted to get rid of it.

It was, however, great fun to drive. With its long gearing, it could go about 60 mph in first gear, and pass anybody traveling at any legal speed in second. On a dry road, it could hang on in the corners pretty well, but in the wet…even if it was just damp…it was a different story. It still had the same tires it had worn in the final laps that it had been driven at Le Mans. I also didn’t know it at the time, but Firestone racing tires (even the ones they used in the Indy 500) were actually rock-hard Firestone truck tires, hand-cut with special grooves. The grooves were immaterial by this time, because the tread had mostly worn away at Le Mans, leaving the tires virtually bald. One day, shortly after I arrived in California, I was in rush-hour traffic on the Pacific Coast Highway, going up a long hill out of Laguna Beach, when I noticed that a slight increase on the throttle pedal would result in the car getting slightly sideways. Bored, I experimented further. A little more throttle and the car would get even more sideways. I discovered I could control the angle easily, and could keep the car 20 or 30 degrees off its line of travel for long stretches. When I got to the top of the hill, I looked in the rear-view mirror. My antics had so scared the drivers behind me that the road was empty.

Another time, at night, I took Beastie out to a deserted road where the Road & Track crew conducted timed acceleration runs for the magazine. After making sure I was alone, I popped the clutch and stomped on the gas. The car went a couple hundred feet before making an ungodly “expensive noise.” The engine had blown. I walked a couple of miles to a farm house (Corona Del Mar was still mainly bean fields and orange groves in those days) and called my friend Shirley to come tow me home with her Volkswagen and an old hawser. It later turned out that one of the engine’s con rods had had a casting flaw. If Cunningham & Co. had ever tried to race with that engine, they wouldn’t have gotten very far.

Fast forward to a year later. I had been fired from my job at Bond Publishing and, after six months looking for another in California, I decided to give up and go home (to my parents’ house in Connecticut) with my tail between my legs. Problem was, I had already bought another car, a robin’s-egg blue 1958 Porsche Speedster (with a 1600 Normal engine, not the troublesome Carrera motor) and I still had Beastie. I was loathe to give up the Porsche, so I tried to sell Beastie. I put an ad in Road & Track’s famous classifieds, but found no takers (although I would be tracked down through this ad 20 years later). I tried to sell her to Chevrolet for their racing museum (but they had no museum…of any kind). I thought maybe she looked too much like a race car, so I paid Earl Scheib (“I’ll paint any car any color for $29.95!”) to paint her Royal Blue (but she looked terrible). Finally, in desperation, I traded her to a Porsche dealer, Vasek Polak, in Manhattan Beach, in exchange for $3,800 worth of race-preparing the Speedster (engine mods, different gears, limited-slip diff, altered suspension, disc brakes, roll-over bar, etc.) and figured I got off easy. Today, the Porsche would be worth maybe $150,000; my ex-Le Mans Corvette is worth at least ten times that.

I never saw Beastie again. Or at least, not for two decades. Vasek Polak had no use for American machinery, so he threw her out in the junk pile behind his work shop. A friend sent me a photo of her in the middle of this forlorn collection of forgotten race cars. Later, someone told me she had been made into a drag-racing car (oh, the humility!). Someone else told me she had been seen in the Bay Area in Northern California. Gradually, I forgot about her. Until one day in the early 1980s when I got a call from a Mike Pillsbury. He was a Corvette restorer and had tracked me down from the ad in Road & Track so many years before. He had re-discovered Beastie, he told me, and was embarking on a restoration project, and wanted to get as much information about her history as he could from me. “How…where…did you find her?” I asked, incredulous. It was one helluva story.

Part Three: Mike Pillsbury

Mike Pillsbury spent a lot of time scrounging through junkyards for Vette parts. He haunted swap meets like the aforementioned one in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and was at the center of an informal network of used-parts vendors that could get anything from the hood emblem of a ’56 Vette to the taillight of a ’76 Sting Ray…and anything in between. In June, 1980, a friend told him about a junk yard in Irwindale, California, that was being shut down the very next day by the Environmental Protection Agency. If he wanted to salvage any Corvette parts, he’d better get over there pronto. So Mike hustled over to the spot and searched the long aisles of abandoned cars. He stopped at one heap. Halfway up the stack was the rear-end body “clip” of a C1 (i.e., first-generation, pre-1963) Corvette. He couldn’t see much of it, but he noticed something odd; something he couldn’t quite place. Inboard of the taillights, on either side of the trunk lid, were a pair of very small auxiliary taillights. He’d seen those somewhere before, but where?

He hurried home and pulled down magazine after magazine from his extensive collection of Corvette articles, stories and automobilia. In the wee small hours, he found what he was looking for. At Le Mans in 1960, the race officials in charge of “scrutineering” (making sure the cars were compliant with the thick rules book) had decided the taillights of the Cunningham Corvettes weren’t “legal” (perhaps because they were combined brake and running lights) and forced Alfred Momo and his mechanics to install a second pair of tiny taillights inboard of the regular taillights. Mike Pillsbury suddenly recognized the car in the junk yard wasn’t just any old discarded Vette, it was an invaluable piece of racing history!

Mike was at the junk yard at dawn the next day, before the EPA crew showed up with their bulldozer to plow the old cars into a shallow grave. Mike offered the owner of the yard $300 for the clunker, threw what was left of the #2 car into the back of his pickup and drove his prize home, elated.

By the time I finally met with Mike at his home in Buena Park, California, he was well along with the restoration, but the car wasn’t running yet. He had contacted nearly everyone who had ever been involved with the car, both on the Cunningham side (like Bill Frick and the car’s crew-chief at Le Mans, Frank Burrell) and on the Chevrolet side. Zora Duntov signed the car before he died in 1996 and Mike had managed to unearth many original parts, even some one-off parts made especially for the Cunningham team, like the seats, the anti-bug air dam on the front hood, and the stainless-steel mesh grille. I brought the only part I had kept (one of the mag wheel hub spinners), the original bill of sale from Don Allen Chevrolet and a sheaf of track notes in Briggs Cunningham’s own hand. I took some pictures of the car in Mike’s garage, and signed a picture of me in the car at Thompson in 1961 for him.

Over the years, I kept in touch with Mike as he would excitedly send me info about some new discovery (the original fuel-injection plenum or whatever) and snapshots of the car’s progress. In 1987, he trailered the car to the Monterey Historics at Laguna Seca for its first public outing. I couldn’t attend, and in any case the car didn’t parade around the track as planned because Mike had installed the clutch backwards (a strange mistake for a Corvette restorer). A few years later, he would bring the car East, to the big Corvette swap-meet at Carlisle. I agreed to meet him there.

The car looked exactly as I had remembered it. The extra hood latches, the bungie cord securing the trunk lid, the running lights above doors, the stainless-steel exhaust-flashing ahead of the rear wheels, the dechromed fenders, the blue velour upholstery, the jerky movements of the big mechanical tachometer, everything. It even smelled the same and sounded the same when he fired it up. It didn’t run trouble-free for the whole weekend, but I did get to drive it partway between the Fairgrounds and town, with crowds thronging the route and cheering us on. It was like a time machine. Magical.

Shortly thereafter, I heard that Mike had died. Of cirrhosis of the liver. Mike was an alcoholic. He had always said the value of the restored #2 Le Mans Corvette would pay for his retirement…but it was not to be. His widow sold the car, in magnificent condition, to a restaurateur on Long Island (for considerably less than it worth, I understand), who in turn sold it to Otis Chandler, a fabulously wealthy car collector (his family owned the Los Angeles Times back when the Times was a great newspaper) who treasured American muscle cars. When Chandler died in 2006, his estate sold the car to Mitt Romney-lookalike Bruce Meyer, another fabulously wealthy collector (a real estate investor), who owns it to this day. The last I heard, it was on permanent display in the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles.

Over the years, there have been various “experts” who’ve debated whether I owned the #2 car or the #3 car, even those who’ve insinuated that I may not even have owned one of the original Cunningham Le Mans Corvettes at all. But I know what I know. When I first took possession of the #2 car, you could still see the faint outline of the number “2” on its flanks (Cunningham had put the numbers on with electrical tape). And the serial numbers match (the #1 car was 3535; the #2, mine, was 4117; the #3 was 2538 – all confirmed in Michael Brown’s documentary of Chip Miller’s restoration of the #3 car). I know the difference. And I always will. You never forget the one that got away.

Postscript

I wrote this piece for my children, who think I’m just some old dude who fixes their bikes and book-bag zippers. “No,” I’ve told them, “I used to be somebody. A real car guy. The Editor-in-Chief of Car and Driver in the Sixties.” “Sure, Dad,” they say, embarrassed for me. So I wrote this to prove my bona fides (not that they’d even know the meaning of the term) by creating an original story out of whole cloth and line-editing it (the kids pointed out that one doesn’t need proofreader’s squiggles in this age of computers). I never planned to see it in print. Then I showed it to Sports Car Digest’s Jamie Doyle and he expressed an interest in publishing it, so I thought I’d better double-check my facts. Knowing that the Corvette faithful were coming to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, last May 6th for the premiere of the movie, “The Quest,” about the restoration of the #3 car by Capt. Jack Sparrow-doppelganger Kevin Mackay (of the world-famous shop, Corvette Repairs, in Valley Stream, Long Island), I wangled an invitation. John Fitch himself was there, still the sharpest knife in the drawer at 94 years old. The #3 car was parked in front of the movie theater, and looked every bit as good as Mike Pillsbury’s restoration of the #2 car. That is to say, perfect.

I sought out Kevin Mackay in the audience. He told me that Briggs later forgave Zora. Fourteen years after the debacle at Le Mans, upon the occasion of Zora’s retirement from GM, Briggs was unable to attend the ceremony, but sent along a hand-written note saying he hoped Zora wasn’t still mad at him for not letting him drive the #3 car. Zora smiled his rueful Russian smile.

Chip Miller, who dogged the unknowing owner of the #3 car for years (“unknowing” because the #3 had inexplicably been restored as an ordinary 1960 Corvette; the airline pilot who owned it was blissfully ignorant of its history) before the owner caved in and sold him the car, had had the dream of reuniting Fitch and the #3 car for the 50th anniversary of the Le Mans race, but Chip died unexpectedly of an incredibly rare disease (amyloidosis; 3,000 deaths a year, worldwide) in March of 2004. Chip’s son Lance, who shares his father’s unbridled optimism for all things Corvette, leaped into the breech, took over the project, and fulfilled his father’s wish. Bob Grossman had also passed away (in 2002), but Fitch, then 92, was there in 2010 with bells on, and drove a ceremonial lap of the Circuit de la Sarthe in the #3 car. High fives all around.

Lance has also created the Chip Miller Charitable Foundation for Amyloidosis Research, so if you want to help, please check it out at chipmiller.org. Chip’s motto was “Life is Good,” and he lived every minute of his life by it. God speed to the Millers and to Kevin Mackay, who has given new life to so many long-forgotten Corvette race cars.

Now, if only they could find the missing #1 Cunningham Corvette. Mackay traced its existence to as recently as 1974, but when he went down to Florida to search the neighborhood where it had been registered, nobody remembered the owner…or the car. My kids probably won’t get this either, but sic transit gloria mundi might be appropriate here.

[Source: Steve Smith]

Kudos to Smith. Alternative title could be “Cars I Have regretted Selling. Although certainly not on a grand scale like the Corvette, my list of regrettable sales includes a ’64 Corvair Spyder whose demise was ensured by Ralph Nader who stopped the progress of US small cars in it’s tracks and who later allowed another American disaster named Bush, a ’65 Mini Cooper S, and a 1986 Porsche 930.

I often wonder who’s loving them, now?

Sam, You may(?) know a little bit about cars and perhaps just stick to them as your comment about Bush is way off the mark. I can think of 16 billion reasons not to like whats happening now to our country. Hope I can afford to keep the classics that I now have. Bill

Indeed, kudos to Smith. What a great read that brings up so many memories of cars missed. My most painful miss was the Aston Martin DB4 GT offered in the high teens somewhere around 1980.

Steve, where in Florida was #1 last seen?

Best “one that got away”story. Mine was 908 that a dentist would trade me for my 912. Mine was street legal.his was broken motor. I passed as I needed a ride to work more than a race car. Stupid life.

Steve:

Great story! It’s always amazing how so many of our famous racers were somehow connected as they plied their trade. The Corvette was a common thread for many, including you as well. How cool is that?

It must have been quite an experience working at R&T. I read R&T from cover to cover as a kid when you were working there. Great mag then.

Speaking of R&T, I used to read and follow with interest the several articles about the Cyclops car, a whimsical beast, to say the least. Lo and behold, Cyclops II appeared at this year’s Amelia! Apparently its concept had bit others with the same bug. What a treat to ‘discover’ that again!

Best to you,

=rds

Steve: As Paul Harvey would say, “Now you know the rest of the story”. A great read. All of us gear heads have the had it and lost it stories…….the car I miss most was the ex-Hulme Brabham BT-8 I bought out of a South Carolina junk yard for $ 2,900. C’est la vie.

Having two friends distract the gendarmes then leaping over a wall and an earthen dike, I ended up in the Cunningham pits at around 10 am at LeMans in 1960. Took a series of color photos with my Leica M-2 of the Corvettes and then on down the line. It’s about time I get my act together and scan these onto a CD. Regards, Steve Snyder

Mr. Smith,

Nicely done. I’ve no doubt grandpa is smiling after reading this compelling story and seeing the images of his beauties fully restored. If you’re ever in the Philadelphia area, visit the Simeone Automotive Museum; they have the Cunningham C4R that won at Sebring, and it still runs like a “beast”. Best regards,

BSC4

Mr. Smith

Congrats on your article, very interesting to me and I’m sure many others. I wonder if I might offer a correction, which if I’m wrong I will apologize now. I believe that the vehicle that Briggs Cunningham bought from Bill Frick was a “Fordillac” It was taken to LeMans as a support vehicle, I believe.

Once again, many congrats.

Damon

Dear Mr. Smith,

Thank you for a wonderful story. And not to worry about the kids – the best part of it is that they’ll come around…

Once again a great story and thanks to SCD for putting it forward.

Looking forward to the next one,

Vincent.

A nice article, thank you for the insight……. A couple of things 10 times $6,000 is only $60,000 I would very much like to buy a Lusso for that amount. Also, the Cunningham money did not come from the meat packing business…….

Brigg’s Dad was an early investor in P&G.

One of my favorite days was when I went to the Cunningham museum in Costa Mesa…. John Burgess and I started talking and in about 10 minutes I realized that about an hour and a half had gone by. That man new his cars.

Great, detailed account by Steve Smith of an amazing saga for Corvette’s first racing event at Le Mans. Steve and part of his story have a role in ‘THE QUEST’, which I wrote & produced and which Steve graciously mentioned in his article. This compelling story is summarized in the film, using archival footage, some of which has never seen before.

A great recollection.

A few comments about my “$2,000” D-Type: I was dropping off a Sadler Formula Junior at Donald Fong’s shop in Atlanta, Ga. when I noticed this D-Type with a damaged right front body being examined by a man taking notes. This insurance adjuster had written the car off as totaled and sold it to me on the spot for $400. It turns out that the “bent chassis” was only the bent front superstructure for the body supports. It wasn’t long before my body fabricator, Mike Saggars and I had a new body corner and repaired superstructure installed.

Since it was illegal at the time to import a used automobile into Canada, I logged the car in as “under repair”. After a season of fun racing with the car , I had to get rid of it back into the USA. I figured $2,000 was a fair price for the car since our repair costs were only a few hundred dollars. While I can’t remember who bought the car, I was sold rather quickly.

A current update: I bumped into Mike Saggars at Silverstone in 2008 after we had lost track of each other for more than 50 years. By a sheer stoke of fate we found out that our same D-Type was at this race. Mike and I visited the car and with it’s current owner – who knew our entire story about his car. And yes, it is currently a muli-million dollar car!

I’m old enough to say I enjoyed reading Steve’s work in both Road & Track and with Brock Yates in Car & Driver back “in the day”. This was such a great article that I posted it on Twitter. I, too have several “woulda, coulda, shoulda” scenarios. First was a 1966 Hertz Shelby GT 350H which I bought in 1969 for $2700 from a Mercury dealer. It was an awesome street car…I used to “eat Corvette’s for lunch”. I kept it for 3 years and sold it for a 1969 Porsche 911L which I then had upgraded with a RS engine swap. When last I saw, on a Barret-Jackson Auction TV show, the GT 350H’s were going for around $200,000……. Second was a 1959 Ferrari 250 GT Coupe which was the personal driver of the head mechanic at Beverly Hills Ferrari. It was in impeccable shape, Ferrari red with valve covers that were so clean you could almost shave off their reflection. The price in 1980 was $15,000. I kept it for 1 day and then panicked….I realized, as was mentioned in the story and a Comment above, that this car would be a very, very risky “daily driver”….especially if and when it came to the inevitable repair and replacement parts bills. So I brought it back to the dealer, got my money back and bought a (Grey Market) 1972 BMW 3.0 CSI coupe with Euro specs and wood dash for $15,000. Great touring car and a wife pleaser……. Ah, but what is that Ferrari worth now!

Steve-

Awesome article, many thanks for taking the time to sit down and document it for everyone to enjoy. I was honored to fulfill my father’s dream of taking the #3 Cunningham Corvette back to Le Mans 50 years later with John Fitch at the wheel! Life certainly throws us all curve balls and I’m thankful I was able to enjoy the ride with Mr. Fitch – it’s a moment I’ll never forget. The ‘Quest’ certainly captured every moment, if anyone is interested in watching the film check out the website: http://questdocumentary.com. Michael Brown and his team did an amazing job at capturing our adventures and sharing the story of each car that raced at Le Mans in 1960. Again, Steve – thank you!

Much respect,

Lance Miller

Thank you, one and all, for your kind comments on this story.

@ Paul in Florida: I’ve no idea where the #1 car was last seen in Florida. You might ask Kevin Mackay:

http://corvetterepair.com/

@ Ronald Sieber & Jeffry Martini: Point of order. The Bonds, John & Elaine (who owned Road & Track) wanted to hire to as the Editor of Competition Press after they bought it from my mentor, Denise McCluggage, but I insisted on finishing college, so they hired Jim Crow. When I graduated, they hired me anyway, and having just bought the execrable Car Life, they set me to work on that. I got to write stories for R&T (road tests of offal like the Humber Super Snipe and a flurry of race reports) but never got on the masthead. Somebody built a Cyclops (originally envisioned as a cartoon by the great Stan Mott) years ago that graced the offices of R&T in the Costa Mesa office where I worked.

@ steve snyder: I’d *love* to see your pics of the 1960 Le Mans. If SCD doesn’t publish them, please email copies to me.

@ Briggs Cunningham: Thanks; I was a great admirer of your grandfather and spent as much time in his pits as he (and Alfred Momo) would allow. He was extraordinarily generous in sharing his experiences (and artifacts) of Le Mans 1960 with me after I bought the #2 car..

@ Damon Crumb & David Randall: I stand corrected.

Loved the Cyclops stories. “You can’t win a rally if you finish ? Minutes late; you also can’t win when you finish ? Hours early.

Steve, that is a GREAT story!

It especially resonates with me because I have recently enjoyed my own “boy meets, loses, and regains car” experience, with the first ’62 Ferrari 250 GTO, s/n 3223 GT. You can read the whole story by Alan Boe in the current issue of Cavallino, #188.

I’m sure you pine a little, as I do, for the occasional opportunity to snuggle up to your old “lover” a little. But it’s a sweet yearning, because you have the great memories and the relatively pain-free intervening years which, had you kept the car, would surely have not been so easy!!!

Thanks again for the super story, and for recalling all those great names in early American motorsport, when we were “boys”.

Sincerely,

Larry

Two other factoids, minor and major:

1. It wasn’t dry ice the Cunningham mechanics packed in around the engine, it was plain old H2O-based ice, as may plainly be seen in this documentary:

http://blogs.insideline.com/straightline/2010/05/corvettes-at-le-mans-gm-shows-off-rare-1960-documentary.html

2. In this self-serving General Motors puff piece, Dick Thompson makes repeated references to the “excellent” brakes. WTF? The brakes started to fade dramatically after the rain stopped. Thompson repeatedly had to slow the car with the engine (months later, when I got the car, the tach’s tell-tale was still stuck way above what Cunningham had specified as the absolute red-line). The over-revving was what caused the engine to blow with a mighty “bang” just as Thompson’s co-driver, Fred Windridge, was passing the pits with about 4 hours to go. Still, nice to see the old “Detroit iron” banging around the Sarthe.

Never say never. The #1 Car from the 1960 Cunningham team has been found! Long thought lost in the mists of time, Kevin Mackay has been searching for it for 19 years, diligently running VIN checks, chasing dead-end leads and staying in touch with his vast army of spotters. The car had last been registered in Florida in 1974, but when Mackay went down there for a look-see, there wasn’t a trace.

What happened was, the guy who owned it all these years was as much a pack rat as a fastidious collector. When he died a few years ago, his son inherited not one but two 35,000 sq. ft. warehouses, jammed with enough automobilia fill Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu. So, it wasn’t exactly a “barn find.”

After a year of digging, the son unearthed the remains of the #1 car, modified almost beyond recognition. Someone had added enough fiberglass to make it look like a Devin-bodied car, but underneath all the Bondo bling, there was the original, mostly intact, even down to the original body (which had been singed at Le Mans).

Curious, he called Larry Berman, the automotive historian who runs the eponymous Cunningham website. Berman in turn directed the guy (whose name won’t be revealed until the car is presented to the Corvette cognoscenti at the “Corvettes at Castile” event later this month) to Kevin Mackay, who did such a magnificent job restoring the #3 Corvette for Chip Miller and his son Lance.

I called Kevin earlier today, who was looking at the #1 car as we spoke. He vouches for its authenticity (as he did with the #3 car when it was “autopsied” after Chip Miller bought it years ago). Kevin will be at the gathering of the Corvette faithful at the Carlisle, PA, fairgrounds this coming August 24-26, along with the (as yet) unrestored #1 Corvette. I hope to be there, too. Y’all come on down!

My brother was Mike Pillsbury, the restorer of #2. To say the least, the restoration was his love, his passion, his life. His family and friends were very privileged to watch a man who got to live his dream. He could name any part of any Corvette not only by sight, but also by feel. I am so glad he got to see his dream realized. It brought a twinkle to his impish eyes! There is a picture of him posing with his #2 on the cover of The Corvette Restorer Magazine Volume #24, Spring 1996. Kudos to you brother! Love, Katie

@ Katie,

I worked with your brother for the better part of a decade helping him restore the #2 car. I was amazed at his diligence, knowledge and enthusiasm. I was astonished that he even found me, so many years after I had owned the car (he had the gumption to coax my whereabouts out of Road and Track, where I’d placed an ad for the car 20 years before).

I unearthed a lot of new information about the car after Mike pestered me to get in touch with my old friend Briggs Cunningham, but on his own he amassed more than I ever could have collected. He was always eager to talk to anybody who had ever had anything to do with the car, and also managed to accumulate an astonishing pile of relevant bits and pieces.

Now that the #1 car has been re-discovered and the Cunningham team is once again complete, I think every fan of the effort at Le Mans in 1960 owes Mike a debt of gratitude for having been the first to track down one of the original cars and restore it to its former glory.

–Steve Smith

Yes, I wish he was alive to have seen all 4 Corvettes. He was always on the road, searching for that “rare” Corvette or Corvette part. It was his passion. Very few people actually get to live their dreams like he did. Katie Pillsbury Skelton

I don’t get it , these 1960 Corvettes never won, why all the hoopla? A poor showing for GM and America far as I’m concerned… Not much different today, Corvettes have NEVER won like the GT 40s….

My “woulda, coulda, and shouldas”….Second place Sebring Porsche RS60 for $ 13,500 (1979), an Abarth Carrera (1976) $2,200. However, my successes, ex-D. Hulme Tourist Trophy winning Brabham BT-8 ($2,900 in 1976 from a SC junkyard) , the Lang Cooper ( $ 6,900…same junkyard), and the 1934 Ford Model 40 Special Speedster (Edsel Ford’s car). You win a few and you lose a few. Just don’t look back.

I have a ‘one I shouldda bought’ story. In the mid sixties I was living in Auckland New Zealand, I would buy a car keep it about a year then sell and buy something else which you coud do without loosing money in those days due to to the New Zealand restrictions on importing cars creating a price situation that I have never encountered since! I saw this beautiful two door coupe on a car lot that at first I thought was a Lancia Aurilia body by Touring but on closer inspection saw that it had a Jaguar engine and running gear and the body was fibreglass. It was a stunning looking car and I went back to look at it several times, the dealer didn’t know much about it and in the end I passed on it. Price wise it would have been affordable for me as around the 500 pounds (about $1000) was my limit. Several years later I discovered that Bernie Ecclestone now owned this car as it was the original Ferrari F1 chassis that had won the 1951 British Grand Prix driven by Froilin Gonzales – it was Ferrari’s first F1 victory. The car had been brought to New Zealand, raced for a year or so then verious mods had been done with the engine finishing up in a boat the body discarded and the chassis sold to renown New Zealand car guy Ferris De Joux who had designed the beautiful GT body and fitted the Jaguar engine etc. Later, after I saw the car someone reunited the chassis and engine and sold it to Bernie where it remains in his collection (I believe) and must be worth several millions of $$$ .Yes I cry everytime I think of it. From Wikipedia…

De Joux bought the Ferrari 375 that José Froilán González drove and won the 1951 British Grand Prix at Silverstone from New Zealand racing driver Ron Roycroft. He converted it into a Gran Turismo that looked like a genuine factory built Ferrari road car. It was an exquisitely proportioned car used by de Joux daily for the next four and a half years until he sold it. The car was restored back to a single seater by a Christchurch classic car enthusiast and is now owned by Bernie Ecclestone.