A few weeks ago McLaren released their new sports car to the public. It’s not fair to really call it a sports car anymore. Sports cars have radically changed since the term first classified these vehicles as lightweight steeds with agile road handling capabilities and spirited performance, more than 60 years ago. These charming cars were surely capable, but quickly gave way to the term Supercar in the late ’60s and early 1970s, when Lamborghini and Ferrari ignited a battle over top speed, cornering power and exclusive pricing. The press loved it, kids argued over it, and enthusiasts dreamed of owning a Supercar. Today, the term Hypercar has become the new buzzword around the top performance offering. This vaulted status encompasses the exclusivity, seven-figure pricing, limited production, and is generally offered in a superlative engineering and design package seemingly lifted from a science fiction movie plot.

The new McLaren Speedtail is all this and more. Hyper priced and performance packed, all 106 of the dedicated production models were instantly spoken for by elite clientele, eager to relieve themselves of $2.25 million for the privilege. Remarkably, the Speedtail manages to unleash a whopping 1,035 horsepower and the capacity to produce 250 mph top speeds, with 0 -186 mph achievable in 12.8 seconds.

The Speedtail is also environmentally friendly, using a gas-electric powertrain, which is docile enough to carry driver and two passengers for jaunts to the grocery store—assuming multi-millionaires actually do their own grocery shopping, complete with two-person accompaniment. The unusual, triangular three-occupant delta seating arrangement encourages unique conversational dynamics between passengers and driver, inviting an angled exterior view for passengers and a direct F1 inspired central seat for the driver – all this happening at four times the national speed limit.

Further technology drapes the wonderfully conceived design including flexible carbon fiber rear tail ailerons that compliantly bend to adjust the rear edge of the car, moderating down force at top speeds. Clearly the car has been developed with aerodynamic focus, incorporating multi-purpose surfacing, complex intake and air management sculpture, and specialized wheel covers. The Speedtail is a tour de force of design and engineering excellence. But the first time I saw it, I wondered where I had seen it before. Why is the overall design so familiar and surprisingly typical?

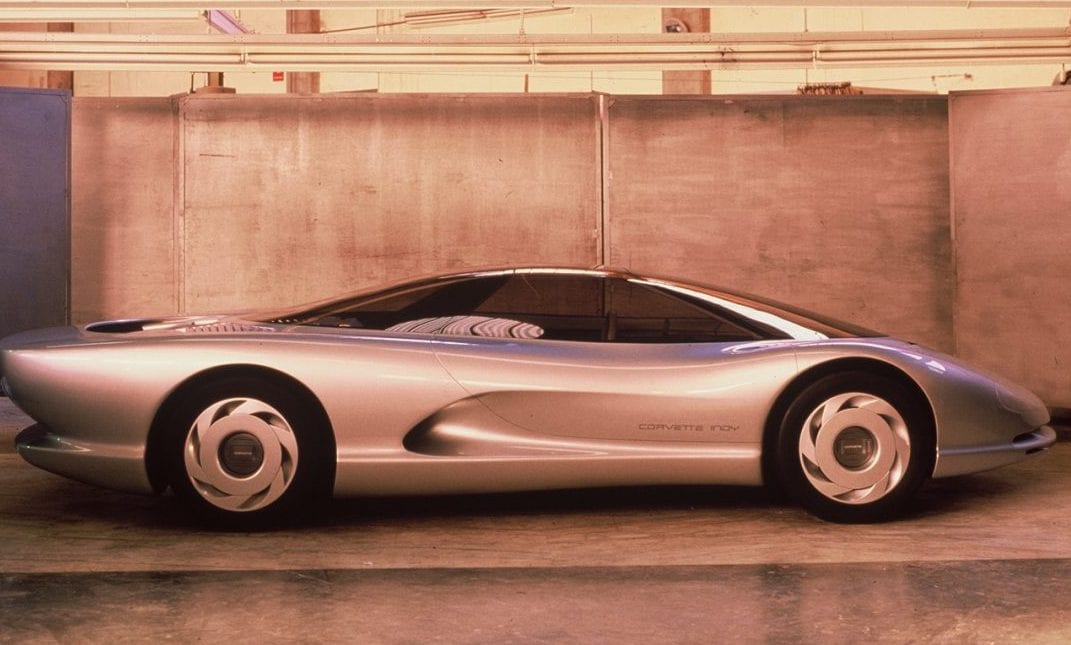

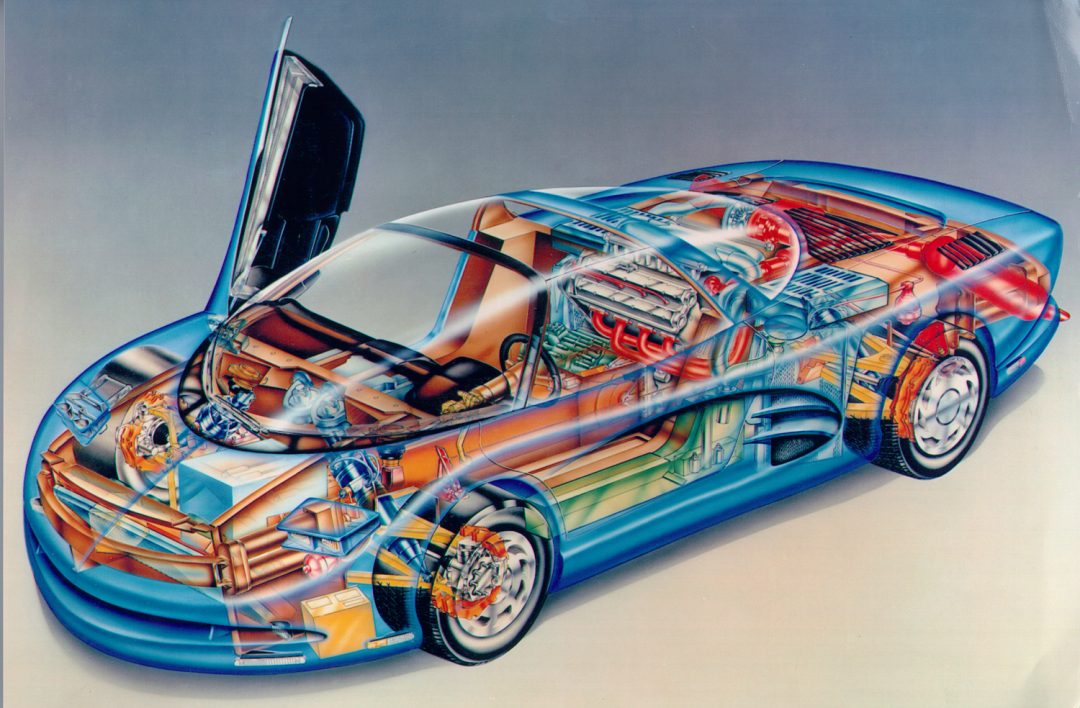

In 1986, General Motors unleashed the beautifully conceived Corvette Indy Show Car. This mid-engine 600 hp concept car was later developed into more refined versions of the initial concept penned by young Tom Peters (GM Lifetime Achievement Award recipient and veteran of Corvette and Advanced Studios Design) working with Jerry Palmer and other highly talented fabricators and engineers. The resultant design evolved into the Cerv III, named in homage to the early CERV I and II concepts, developed under legendary Zora Duntov.

These cars, both in conceptual terms and as inspirations for GM production cars and a wide range of other auto makers, inspired a revolution of sinewy, fluid, organic body designs innovated by a handful of talented designers at General Motors. And while many of these talented designers may never be specifically named for their exceptional work during this renaissance of sports car design in, of all times, the 1980s, it is wholly appropriate to review the comparisons between the ground breaking Corvette Indy Show Car, Cerv III and, more than 30 years later, the all new 2019 McLaren Speedtail.

The Corvette Indy was conceived when the IBM PC was only five years old, the Apple Mac just two years on the market, Nintendo gaming was brand new, and autofocus cameras using rolls of film were considered leading technology. The car industry was only beginning to experiment with computerized systems and drive mechanisms, hybrid cars were dreams of the future, and the very first Japanese Luxury Sedans were just on the horizon. So when GM unveiled the outrageous Indy Show Car, the gauntlet of design was thrown down to anyone watching. Three decades later, McLaren paid close attention and released the Speedtail. Both cars share tapered tails, elongated shapes exceeding contemporary sedan dimensions, low jet-fighter inspired rooflines, mid-engine designs, flat surfaced wheel covers, and a generally similar vehicle architecture both in the upper glass area, tumblehome, and overall surface development. The Indy, like the modern Speedtail, was loaded with technological innovations like GPS navigation, electronic throttle control, selectable all-wheel steering, and Lotus derived active suspension with microprocessor-controlled hydraulics to aid in precision wheel positioning and power delivery (an early version of active ride control). Even the scissor doors are similarly designed, though McLaren opens the roof section as well.

The striking similarity between these two designs, and the years that separate their execution, begs the question – Have we reached a sports car zenith of design? I believe so. But it is not because of universal technology, advanced aerodynamics, or preferred practices in computer-aided design. Rather it has more to do with our growing hesitation to build expensive objects, at great risk, coupled with unique visual signature. McLaren cannot afford to take the kind of risks that GM can with their concept cars. McLaren clientele want a car that is visually similar to other cars on the road today, laced with hints of innovation and dripping with bespoke materials. It is, after all, a $2 million dollar toy. If it strays too far from accepted visual icons of modern sports car ideals, wealthy people will not be be willing to take the risk on a visually challenging design.

As prices rise on these exceptional hypercars and demand for the exclusivity continues to pervade the highest levels of the marketplace, there will always be a place for a highly expensive exotic car. But until a company is willing to take a big leap of faith and gamble on truly unique visual architecture, radical surfacing, and ground breaking engineering, we will have to limit our delight to conceptual reboots of beautifully conceived designs as variations of greater conceptual risks from decades ago.