I love good pesto. It has all the right ingredients for a wonderful meal. Cheese, basil, olive oil, all ground (Italian “pestare” to crush) together with pine nuts and just a hint of at least one other secret ingredient which, depending on where you’re from, is a key ingredient that makes your particular family pesto something special. Pesto recipes have been modified for many years, but most generally agree that pesto is Italian and should, therefore, contain Italian ingredients. But every once in a while, something changes a recipe, resulting in a magnificent pesto with surprising results. Such is the case with the Alfa Romeo Montreal. A brilliant and crushingly powerful pesto of Italian origin with a surprisingly Canadian inspiration and namesake.

Italians and Canadians have a long and rich history together. Italian migration to Canada was robust throughout the 19th and 20th century and continues today. In 1967, the Canadian Montreal Expo invited the world to visit Canada with the enticing theme “Man and Technology.” The organizers contacted Alfa Romeo and Bertone requesting a concept car that would reflect the very latest in sporting technology. Of course, the flattered Italians complied. Bertone elicited the prodigious skills of Marcello Gandini who responded with a fastback coupe reminiscent of his incomparable Lamborghini Miura. Offered as a 2+2 coupe with the typically seen Alfa overhead cam, four-cylinder engine, two prototypes were displayed at Montreal to surprisingly high acclaim. Interest rapidly grew for the novel sports car, though still lacking a proper name.

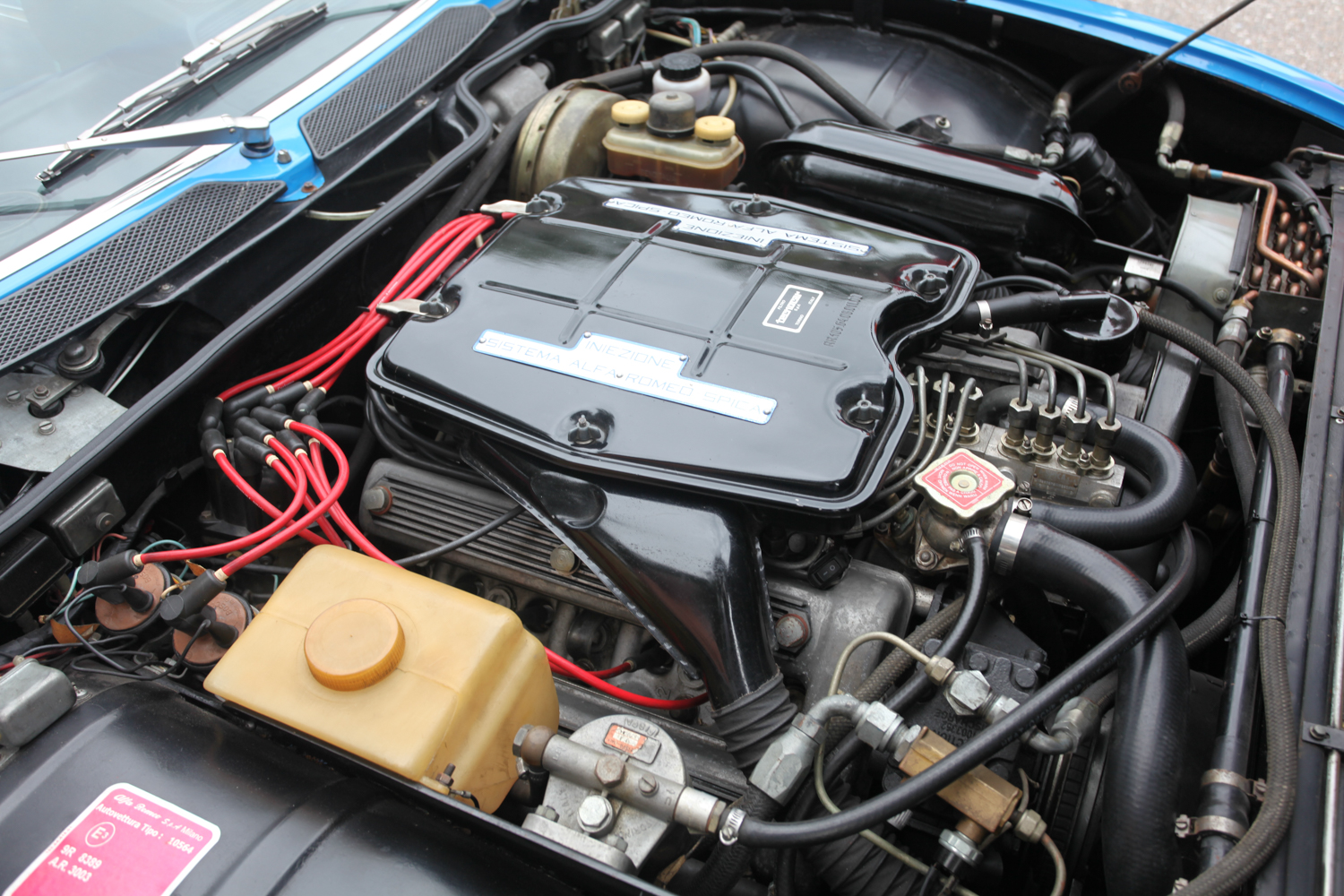

Perhaps it was the times, the energy of the rapidly moving ’60s, or a hint of Italian bravado, but in no time at all, the new Alfa concept became the darling of the automotive press and adoring fans of the Alfa brand. Italian bravado once again at play, Alfa and Bertone immediately began development on the car that would come to be known as the “Montreal.” By the time it arrived as a production offering however, the new design was radically different, quite expensive, and remarkably unavailable in Canada or America due to emissions restrictions. Though roughly 4,000 units would be made over its six-year run, Alfa Romeo blindingly pulled out all the stops in their effort to prove that Italy was the pinnacle of Man and Technology, just as the initial theme at the Expo had so eagerly promised. No longer a four-cylinder engine, the larger 2.6-liter, quad-cam V8 was nothing short of a refined race-bred engine, derived in fact from the Tipo 33 series racecars. This amazing SPICA fuel-injected engine, coupled to a 5-speed manual gearbox—flanked at all corners with disc brakes, front double wishbone suspension, and live rear axle—made for a true supercar in all respects. But it was the unmistakable body design that would attract everyone, a uniquely derived design that would put the finishing touches on the end of the golden era of sports car design.

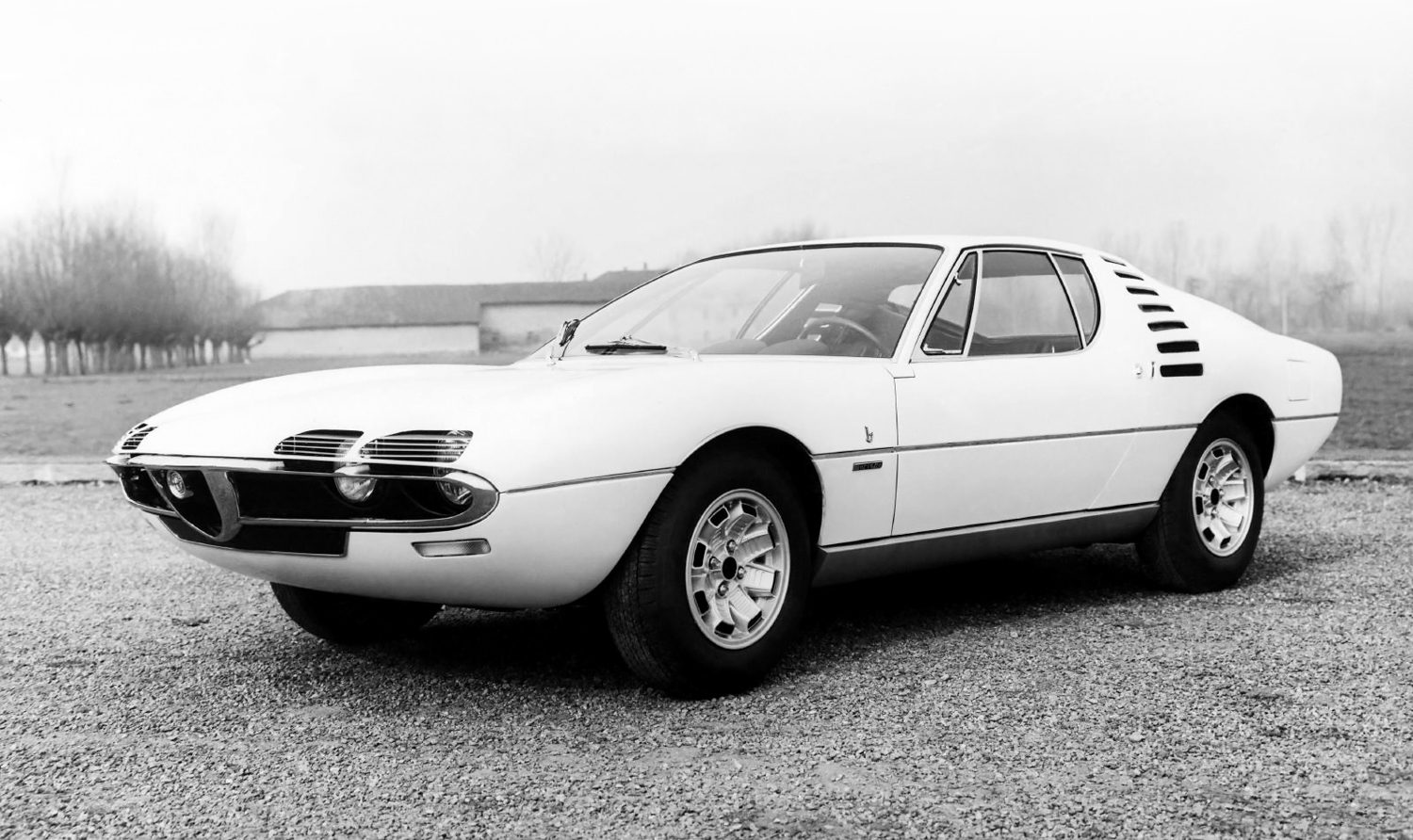

Seeing a Montreal in person, your first reaction is how immediately compelling the overall shape and scale truly are. The Montreal is small by contemporary sports car standards, but it has a wide and confident stance with a broad hood concealing a V8 engine, and yet a short rear deck beguiling space for (albeit small) rear passengers. Within moments of understanding the proportions and scale, your next impression is that literally every view has a unique design element gracing each body panel.

The perimeter grille features vented retractable headlight trim, the hood houses a NACA duct (one of the first production cars to use this element), the rear features a full width glass hatch and Kammback tail, the doors feature a Miura-like upsweep into the body upper, and perhaps the most memorable and distinctive aspects of the design, the sail panels feature a set of six dramatic rectangular venting slats.

The side vents, applied as a thematic concept to both the hood and side panels of the original concept, were fresh and contemporary. The side vents created a visual strobing of energy that broke up the visual height of the Montreal but also visually reduced the mass of the body colored sail panels, concealing the rear seats. Having cribbed heartily from the Miura, it’s possible that these design elements were enlarged details captured from the delicate door venting in the Miura. Other obvious Miura features include the distinct rear fender haunches, windshield to side glass proportions, eyelash headlights, and fastback roofline. But for as much as the Montreal owed the Miura in design, it also departed greatly from the early 1960s with a novel approach to sports car design. The central body line divided the tall side mass, the modern NACA duct added space aged panache, and the wide interior cabin made for a surprisingly comfortable supercar with all the performance and prestige of a two place sports car.

Studying the Montreal, it’s tempting to wonder how it might look without the distinctive side panel design. Removing these design elements shows almost immediately how important these features are to the overall design of the Montreal, and not simply a clever gimmick of visual distraction. So important are the proportions, pacing, and scale of these side vents that even the removal of one of the six elements makes the design appear more rotund and less urgent. The strobing effect that Gandini captured with his design was most certainly the inspiration behind John Herlitz’s design of the 1971 Road Runner, which shares many familiar themes, but primarily in the strobe effect over the C-post, also using six side panel segments.

Captured with great Italian passion and delivered through the vision of Canada’s hopeful future of man and technology as it debuted at the 1967 Montreal Expo, the Alfa Romeo Montreal remains tastefully unique, a blend of Italian performance and style, with the spark of Canadian futurism – perhaps it was the finely ground Maple leaves that were the secret ingredient to the Montreal’s magical pesto.