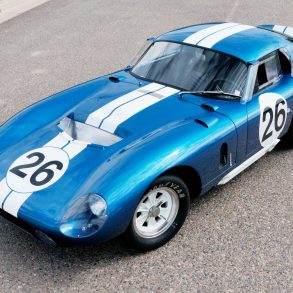

History lauds volumes of praise to those who are first. Thinking back to 1964, many will recall a short wheelbase, two-seater with British origins delivered to the U.S. where a 289 high output engine was installed and it sold worldwide – the Shelby Cobra. But there was another car that followed a nearly identical path, hot on the heels of Ol’ Shel – the Griffith 200.

Using essentially the same body design as the TVR, the Griffith 200 and later 400—largely distinguished from the earlier model by a vast, sweeping fastback rear glass—were potent cars offering unique styling and very capable performance. Jack Griffith, the performance-minded namesake and owner for the U.S.-based Griffith Motors, worked with a simple if not familiar purchase plan for his cars. Take advantage of the UK built TVR, deliver it to the U.S., load it up with go-fast goodies, and sell to sports car enthusiasts. Of course, it didn’t hurt matters that TVR was, to say the least, one of the most progressive and imaginative promotors of sports cars… a subject for another time. Despite selling 192 production 200s and 59 400s, low numbers by any production measure, in 1965, the fledgling company somehow convinced themselves that an all-new, non-TVR derived sports car design would increase sales. Precisely the same time Shelby was working on transitioning to the new Mustang platform.

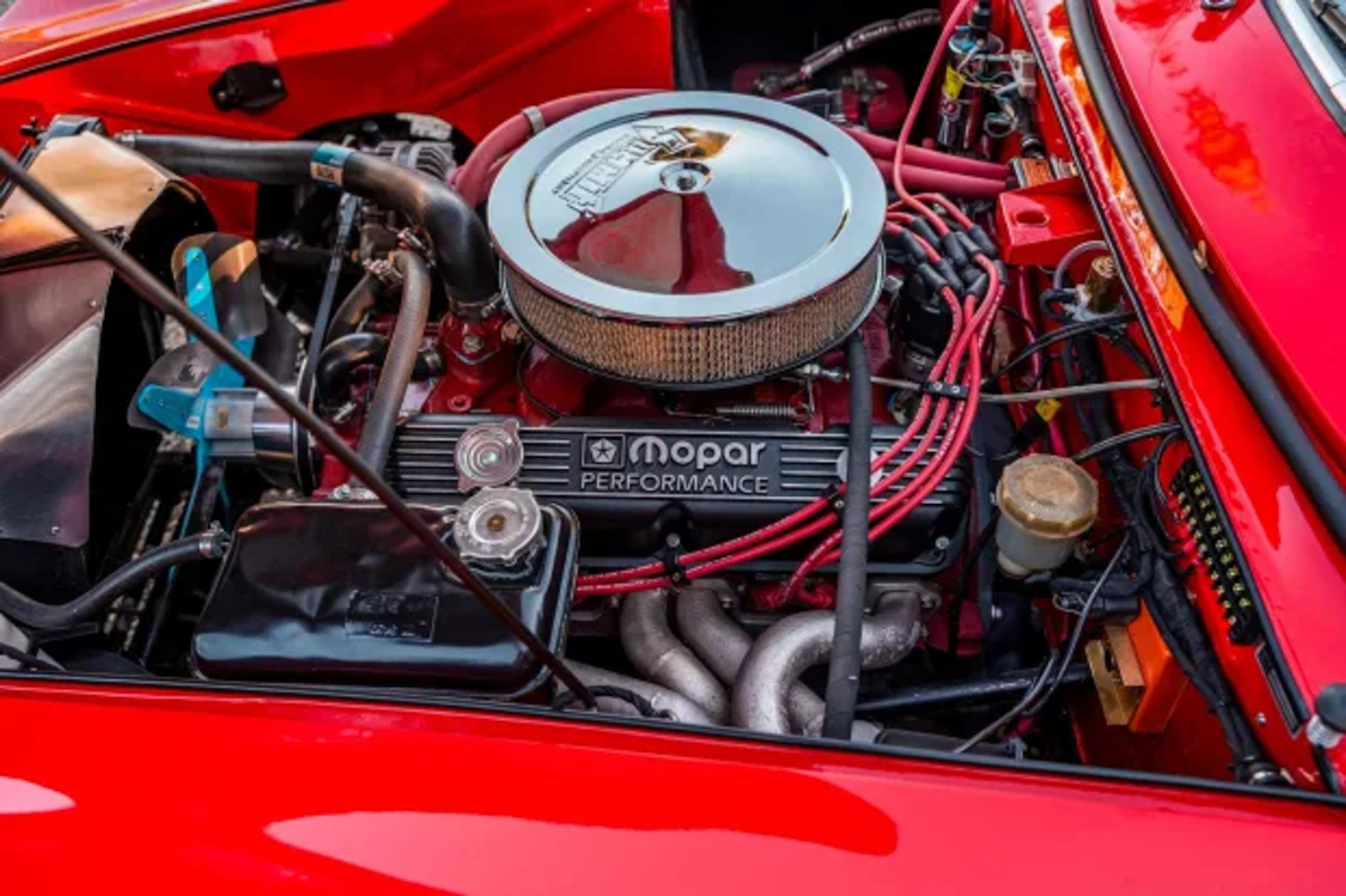

The Griffith 600 design was assigned to Robert Cumberford and commissioned to all-steel construction with Frank Reisner’s Italian-based Carrozzeria Intermeccanica. Originally designed to accept the 289 Ford driveline, a lengthy shipping strike delayed delivery forcing the Griffith 600s to be built with Chrysler 273 engines. Arriving in late 1966, the car was beautifully designed and constructed by skilled craftsmen in Italy and delivered to the U.S. Poorly timed against the shift to Muscle Cars, the ambitious Griffith 600 ultimately could not outpace lackluster sales. Under crushing debt, Griffith shuttered the operation after delivering just six production units. The following year, the same design was reinvigorated first as the Omega (33 examples built in 1968, by then with the 289 Ford engine), briefly as the Torino, and finally as the Italia, primarily as a convertible.

To understand the design, it’s important to consider the career of Robert Cumberford. Schooled at Art Center College of Design, Cumberford was hired by GM prior to finishing his degree. Yes, he was that good. Credited with work on the ’56/’57 Corvette, various Cadillacs, and Buicks, Cumberford departed GM to pursue a host of other projects, study philosophy, and work with legends Holman & Moody in the 1960s. Now highly regarded for his writing and editing work in more recent years, it is easy to forget that the Griffith 600 was both a fresh beginning and an immediate ending to a brief but exciting period in American sports car design. The Griffith 600 not only captures a rare moment in sports car history, it challenges a subtle blending of European design with American power and refinement.

The first thing that strikes you when seeing the Griffith 600 is how clean and pure the car is. Themes are evident from Italian designs of this era, but clearly refined. Other than the front and rear chrome bumpers, the design is virtually void of any decorative trim, vents, accessories, or otherwise unnecessary jewelry. In the original design, the grille is placed under the front bumper. However, this was changed to allow for more air intake using split front corner bumpers, largely attributed to improved engine cooling. The headlights are recessed into the front fender lines, and the Kamm back tail is void of any decorative trim. Later series Italias would add side vents to exhaust engine heat and other changes, but the original Cumberford design would remain throughout all iterations. Even the door handles are nothing more than push button affairs with a small pocket to rest your finger to open the door.

The Griffith 600 hood is wide and long, yet tall at the cowl before diving down to the shin high bumper. The floating hood, itself no easy feature of fit and manufacture, starts at the cowl and drops down quickly, hiding behind the progressively arched and delicately creased front fenders. Cumberford’s design was clever in many ways, but this feature boldly carries the frontal theme in a dramatic drape when viewed in the side and front views. Like the 289 Cobra, the tall cowl perfectly accommodates the high profile V8 engine, pushed back into the cowl, limiting the peek effect of the rising cockpit. Cumberford cleverly rakes the forward sail panel line towards the front of the car, matched by the door cut sweep, and then angles the rear glass line of the trailing sail panel in the opposite direction. This further elongates the sharply peeked canopy and draws your eyes downward. Completing the rear design, the surprisingly spacious trunk is surrounded by visually slimming concave elements that trim the otherwise hefty trunk into a handsomely integrated rear lip assisting air flow to the Kamm back tail panel.

The long hood and short deck proportions are typical of the dramatic front engine, rear drive sports cars of the 1960s, but with the light look and feel of the Griffith 600, the wide stance, combined with wide wheels and tires, delivers an overall look that is familiar, while still retaining a unique signature. Certainly, the design was influenced by a rare combination of European sports cars and did further influence future European sports car designs, but these budding American design ideas were largely relegated to concept cars from the Big Three. Other than the Corvette, there was no other American sports car design in volume production. By the early to mid 1960s, emphasis was being placed on Muscle Cars and 2+2 configurations favoring a combination of performance with space for families. Although the Griffith 600, Omega, and eventually the Italia were great looking cars, the audience for these cars simply never arrived in large enough quantities to justify a market. Pontiac, having toyed with numerous two place offerings for years, finally showed up decades later with the Fiero, but as a “commuter car”.

Beautiful by any measure, unique in stature, and rare in number, the Griffith 600 and subsequent Omega were the right car at the right, albeit brief time. The Griffith was perfectly timed to deliver a powerful, front-engine sports car to compete against European competitors. A time that would come and go in a matter of a few years as the juggernaut of Mustangs, Camaros, and Barracudas would begin their dominant performance reign on American soil, one that would also eventually find its demise by the early 1970s.