The region of Cortina d’Ampezzo has been, for the last half-century, one of the most coveted places in the world to practice extreme sports. In summer, hiking, gliding and base jumping are the main attractions, while in winter, snow and ice sports dominate the scene of the picturesque city nestled in the heart of the Dolomites.

The place’s tradition of such sports was the result of decades of encouragement, mainly through major competitions that attracted the world’s biggest names in these categories. For example, the city has hosted international championships in alpine skiing, figure skating, bobsleigh and other snow-based sports on several occasions.

But without a doubt, one of the most important events in the history of the town was hosting, in 1956, the Winter Olympic Games. For 10 days, Cortina was the epicenter of world sport, attracting visitors’ eyes not only to the magnitude of the event, but to the natural beauty of the place itself.

The event was important for a wide range of reasons: the first was undoubtedly to put Cortina d’Ampezzo on the map, which until the early 50´s, was a small town with no more than 6500 inhabitants. During the winter season, the place was frequented mainly by Italians, Austrians and French, who knew the ways to the small city. But after the success of the Olympic games, Cortina entered the spotlights, as the city became a much more bustling, vibrant and internationalized place.

The developing project of Cortina d’Ampezzo to host the games was extremely important in this post-Olympics movement: better infrastructure meant that the place could receive a greater number of tourists, which, consequently, would boost the local economy. Therefore, by the end of the 1950s, Cortina had grown to be one of the best-known winter resorts in Europe.

With its rapidly expanding popularity by the end of the 50´s, Cortina was looking for other advertising opportunities that could differentiate it from other places, such as attractions and entertainment that would be its ‘personal brand’ compared to other destinations. This is where the idea of hosting a Formula race in the snow comes up, with the beautiful peaks of the Dolomites as a background.

Racing On Ice

Even though Italy had no tradition of hosting races on snow or ice, this type of event was nothing new on the international automobile scene. On the contrary, in the pre-war years, races such as the Norge Grand Prix (Norway) and the Sveriges vinter-Grand Prix (Sweden) had their share of interested parties, who were always looking for new challenges, very different from those imposed on traditional circuits of asphalt, bitumen or concrete.

In the 1950s, the event that began to stand out in this format was Prof. Dr. h.c. Porsche Gedächtnis Zell Am See Eisrennen, in Austria. The event originated in 1952, and until the end of the decade, it attracted a legion of faithful followers, who migrated to the city of Schüttdorf to watch the events on the frozen waters of the lake Zell. Not surprisingly, the event served as a template for the expected race in Cortina.

Another point that positively favored the region of Cortina d’Ampezzo was that it already had some know-how about hosting racing events: beginning in 1947, always in the month of July, the place hosted the Coppa d’ Oro delle Dolomiti, a competition that always attracted big names of the international motorsport. The race, which took place on the winding roads between Cortina d’Ampezzo and Belluno, became one of the biggest events on the region’s sporting calendar during the 1950s.

However, in 1957, the race was abolished by the Italian government itself from the official calendar of automobile events, largely due to the still present memories of the 1955 Le Mans disaster and Alfonso de Portago’s fatal accident in the 1957 Mille Miglia, which profoundly shook the pillars of world motorsport.

The main problem of the Coppa d’Oro was its ostensible use of public roads, on a treacherous route of more than 300km in length – which prevented any effective attempt to introduce safety measures across the entire track. Furthermore, other points related to the route began to increasingly displease the pilots who were going to participate in the race: such as the high altimetry, which forced pilots to make an almost superhuman effort to control their machines on the ascents and descents of the Alps passes. Another issue is that parts of the circuit were still of gravel surface, meaning that the race looked more like a rally than a GT car event.

Then, the Automobile Club Belluno, responsible for organizing all automobile events in the region, stepped in, trying to explore viable alternatives for a replacement of the Coppa d’Oro. And this search coincided precisely with the rise of a new category on the Italian scene: the Formula Junior.

Conceived in 1957 by Count Giovanni “Johnny” Lurani, Formula Junior was an initiative to try to re-engage Italian drivers in an international motorsport scenario. The marvelous Italian generation that had led the sport in the 40s and 50s (with names like Farina, Ascari, Viloresi, Taruffi, Castelotti and Musso) had died on the tracks or was about to retire, leaving a huge void at the forefront of Italian motorsport.

Another factor observed by the Count was the large gap that now existed between the lower formulae categories, which raced at national level (such as F3 and the F2 national championships) and those that were linked to the international circuit (represented by the European F2 and the F1 itself). There was a gigantic economic and sporting abyss, where it was increasingly unfeasible for small manufacturers to enter the big races.

Therefore, the timing couldn’t be better for the conception of a new category, which would bring together the lessons of a careful observation of the international sporting scene. Formula Junior quickly began to gain fans and, in its first year (1958), the category had already gone beyond the borders of Italy, with races being held in France and Portugal. 1959 promised to be a fantastic year for Formula Junior, as now several other countries, after seeing the resounding success of FJ races, signaled positively for the category’s inclusion in their own sporting calendars. And Cortina would be the starting point of this journey.

The Machines

Since Formula Junior had its roots in Italy, it was impossible for the builders from the boot-shaped land not to come out with the upper-hand in the first years of the category. In addition to the undeniable Italian tradition in the construction of racing cars, there were other factors that contributed to the rapid diffusion of the FJ in the country; such as the good supply (at low prices) of parts for the construction of these vehicles, in addition to the Italian economic boom of the late 50s, which transformed Italy into the mecca of Formula Junior in the category’s first steps.

Most FJs between 1958 and the early months of 1960 used the most ordinary engines possible, which could be easily found anywhere in the country. The largest representatives of this group were the Lancia Apia´s and FIAT 103´s, both with 4 cylinders and 1089cc. The biggest difference between the cars was the body and chassis, which often sought to be based on designs already proven in higher classes.

The Stanguellini, almost all of the 1100 model, were the most popular cars in the Italian FJ era. It was a compact, simple and reliable machine, retaining some similarity to the F1 cars of the time. And this is no surprise, since the Stanguellini was the result of the joint-effort of engineer Alberto Massimino and Ginacchino Colombo – both were collaborators in the development of the Maserati 250F, the car that dominated F1 in the mid-1950s.

However, beneath the graceful aluminum body, any resemblance to the more elaborate F1/F2 cars disappeared. The car had a simple ladder chassis structure, in which the FIAT engine was positioned at an angle to the right of the car’s center line, while the driver sat slightly to the left of it.

But it wasn’t just the Modena constructor that made a name for itself at that time. Arzani-Volpini, created in partnership between Gian Paolo Volpini and the engineer Egidio Arzani, also ventured into this new category.

For those passionate about 1950s motorsport, the name Volpini shouldn’t sound strange – and there is certainly a reason. Between the years 1954/55, Scuderia Volpini participated in some F1 non-championship races with a Maserati Milano-Speluzzi 4CLT, before Mario Alborghetti destroyed the car in a terrible accident at the 1955 Pau GP.

After this adventure, Volpini and Arzani turned to more traditional paths, seeking to establish themselves in the Italian F3 scene. And when it began to give way to Formula Junior, it didn’t take long for the duo to come up with a new project that fit into the new category.

The Volpini-Fiat 1100/103 was a car that basically followed the same style proposed by the dominant Stanguellinis. The driver’s cockpit sat offset to the left, allowing the transmission and gearbox to be fitted on the right side of the car. This arrangement was adopted by several manufacturers, as it helped with the car’s balance while also cutting the costs of carrying out an entire central installation, as in most high-performance cars.

A special detail of the Volpini FJ were the engine cylinders. The Volpini Cylinder head (model H) had four intake ports, with larger passages than the normal FIAT 103/1100 unit. At the time, the Volpini type was the only special head permitted under the Formula Junior rules, since the category advocated the use of production parts in cars.

Other small Italian construction companies also wanted their share of this promising market: Foglietti, a small firm located a few blocks from the center of Milan, began building its models at the end of 1958, seeking to put into practice some of the lessons learned from the first year of the Formula Junior. Mr. Ernesto Foglietti’s cars were another example of copying Stanguellini’s basic design: gearbox and transmission on the right, driver on the left.

However, it was Tarashi who was the first to pose a real threat to the overwhelming number of Stanguellinis on the grid. The company offered a car almost identical to the 1100 model, except that it had a more traditional pilot-engine arrangement, with both following the center line of the car.

On the other hand, some Italian companies were already beginning to pay attention to the rear-engine revolution, which was taking Formula cars by storm at the end of the 1950s. Wainer and De Sanctis, as early as 1959, began to offer cars using this new technology in the Formula Junior. Furthermore, these cars had spaceframe chassis, which were much more advanced than the ladder structures used by front-engined Formula Juniors. Even so, both the Wainer and De Sanctis did not find great commercial success, being overshadowed by the cost and practicality of front-engined cars.

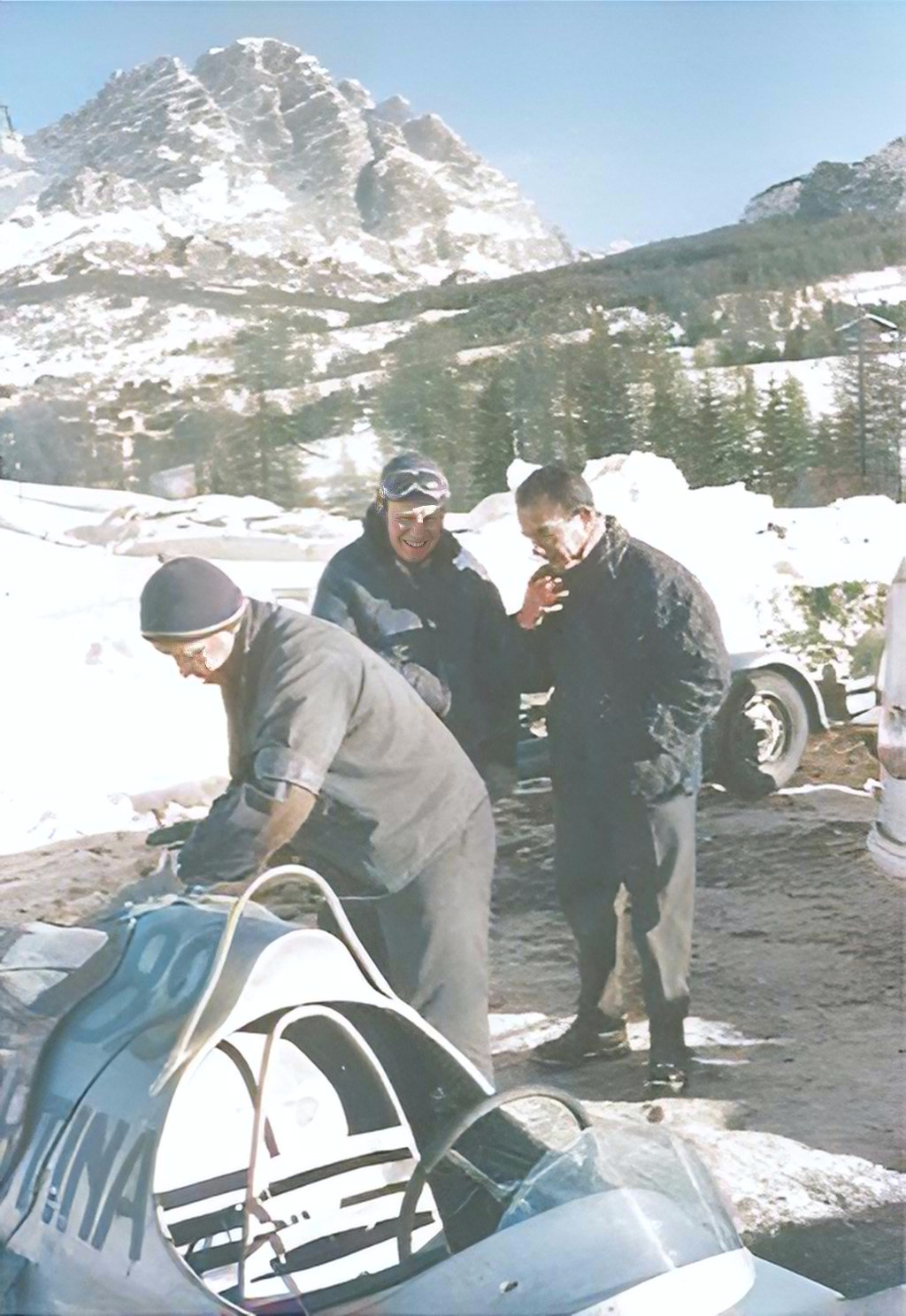

Departing For Cortina

Italian representatives showed up in force for the ice race, officially scheduled to take place in mid-January 1959. In addition to the ever-present Stanguellinis, also Volpini, Foglietti, Raineri and Wainer had representatives in the race. Furthermore, there were two other very peculiar entries on the grid.

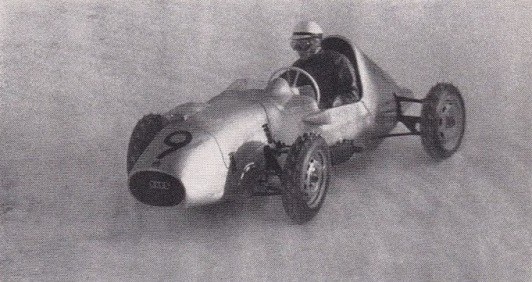

The most spectacular case was undoubtedly that of Otto Mathé. The Austrian, who gained fame for his performances in motorcycle racing, had to change the two wheels for four after a near-fatal accident in September 1934. Being an inventor and passionate about speed, Mathé never distanced himself from motorsport, always seeking new experiences.

With his long resumé of victories, it is impossible to select one factor that defines Mathé´s entire career. But, if this could be traced, it would be the construction of the ‘Fetzenflieger’. The car was a true Frankenstein of its time, being a mix of Porsche and Volkswagen parts. Originally built in 1952 for F2 specifications, the car remained competitive throughout the 1950s, achieving good results due to the constant updates to the machine promoted by the driver.

For Cortina, Mathé had installed a Volkswagen AU 1000 engine. Even though inferior in gross power to the FIAT 1100, Mathé hoped to compensate for this factor with better weight distribution and traction of his car in the snow, since the ‘Fetzenflieger’ was an extremely sleek car, which was also rear-engined.

Also causing a sensation upon his arrival in Cortina was Gerard Laureau’s DB–Panhard; not only because of its beautiful royal-blue finish, but also by the virtue of the model´s peculiar story. The car, known as ‘Monomill’, the word being the french acronym for monotype moins de mille centimetrès cube (in english, monotype with less than a thousand cubic centimeters) reflected the car’s low original displacement, and was initially conceived as a project by Charles Deutsch and René Bonnet for a racing vehicle that would fit the 1955 F1 specifications. But the car never raced in the category which it was designed for, and was later used in F3 and, consequently, in Formula Junior.

In order to be accepted in the FJ rules, the ‘Monomill’ underwent a complete remodeling process – not much in terms of aesthetics, but substantially in terms of mechanics. The cars’ original supercharged DB-Panhard engine was replaced by an 851cc small block (which was later upgraded to 954cc) also built by the French manufacturer. Furthermore, the special brakes, custom-made for the car in its original version, had to be replaced by serial produced brakes, as stated in the FJ regulations.

But in the end, the factor that would make the main difference in a category as balanced as Formula Junior would be the drivers. Roberto Lippi, who had been champion of the Italian Formula Junior in 1958, was without a doubt the strongest Italian representative in the Cortina race.

In addition to him, other names that stood out in the 1958 FJ season also packed their bags and left for the Alpine region of Italy: Gastone Zanarotti and Carmelo Genovese, who had achieved victories in the same championship, promised to provide tough opposition to the champion Lippi. Another name that also deserves its mention is that of a still unknown Lorenzo Bandini, who even though only took part in his first single-seater race the previous year, already showed signs of being a driver with a promising future.

The Corsa Sul Ghiaccio A Cortina D’Ampezzo

At the end of the registration period, just under 20 drivers had shown interest in attending the event in Cortina d’Ampezzo; and, when the day of the races actually arrived, only 14 machines were present at the site. It may seem like a ridiculous number, but if you take into account that it was a test event, with very peculiar competition conditions, it ended up being a reasonable number, which even surprised the organizers positively.

Much of this presence can be credited to Sicilian Marcello Giambertone and his intense relationship with Formula Junior. Before his involvement with the category, Giambertone was an already known figure in the paddocks of world motorsport, largely due to his relationship with J.M. Fangio, as he was the Argentine driver’s agent and close friend.

After the five-time F1 champion said goodbye to the tracks in 1958, Giambertone, without his greatest asset in motorsport, found an exceptional path in Formula Junior, supporting the new generation of Italian drivers. To achieve this, the businessman founded Scuderia Madunina, which would be one of the biggest teams of the Formula Junior era.

In addition to functioning as a semi-works team for Stanguellini, Scuderia Madunina operations in FJ offered a series of services to third parties, who had purchased cars from the Italian constructor. For example, the Scuderia offered a package for independent drivers, which involved transport, mechanics and all the bureaucratic aspects of registering for races. As a ‘gift’, the drivers were registered by Scuderia Madunina itself, appearing on the entry lists as official members of the team. This partly explains the large number of drivers registered by the team in the FJ years – and the race in Cortina d’Ampezzo was no exception in this case, as the Scuderia would have 8 representatives in the race!

In the end, the race would be held on a 1200-meter-long circuit, built in a place called Campo di Sopra, close to the frazione (which is the Italian analogue of a parish) of Mortisa, on the outskirts of Cortina.

The track itself had a counter-clockwise layout that resembled a boot: the drivers started on the main straight, and, after a hundred meters, they made a 180° downhill turn, which took them to the opposite straight. Another hundred meters, the pilots made a gentle turn to the right, which ended in a brief zigzag, that soon gave way to a sharp curve of almost 270° to the left. This large curve broke abruptly into another curve to the right, which led to a small straight, where the improvised pits were located. Arriving at this area, it was almost the end of the lap, with just one more left turn remaining to enter in the main straight again.

The Cortina track was planned so that drivers could take advantage of various lines of the track, as the ice and snow allowed other driving styles to stand out – for example, taking turns well-adjusted with tangents might not be the best strategy all the times, as the wear of the track over the laps could mean that the inside part of the curve was slower than the outside, less used. Therefore, this time, it was up to the drivers to worry more about the wear on the track than that of their own vehicles.

The chosen competition format was a series of eliminatory heats, which would culminate in a ‘grand finale’, involving the fastest drivers. And, with that in mind, the activities began on the Cortina d’Ampezzo circuit.

The first stage consisted of the formation of two groups with seven drivers each, who would compete in a heat of ten laps. The first group to enter the track was made up of Carmelo Genovese (Stanguellini/Fiat), Dino Montevago (Foglietti/Fiat), ‘de Carli’ (Stanguellini/Fiat), Gastone Zanarotti (Volpini/Fiat), Giovanni Alberti (Stanguellini/ Fiat), Nino Crivellari (Stanguellini/Fiat) and Otto Mathé (Mathé/Volkswagen).

After a shaky start, Mathé soon took the lead in the heat, demonstrating that his rear-engined car was much more balanced on the snow than the front-engined Stanguellinis. His closest pursuer was Giovanni Alberti, who was putting on an excellent performance, being just a few seconds behind the Austrian driver.

The first serious accident of the race happened on the sixth lap, when Zanarotti lost control of his car and hit one of the snow banks on the side of the track, causing his Volpini to roll into the middle of the track. The stewards quickly arrived at the scene of the incident, and the car was put back on its wheels.

Both driver and car were almost unscathed, and the pilot continued the race, finishing 2 laps down the winner, Otto Mathé. Alberti, the closest pursuer of the Austrian, finished 3.5s behind, in the second spot. Rounding out the top-3 in the heat was Nino Crivellari, already far behind the two leaders.

Now it was the turn of the second group to make their presentation: Bruno Gavazzoli (a.k.a Madero, Stanguellini/Fiat), Corrado Manfredini (Wainer/Fiat), Gerard Laureau (DB/Panhard), Gino Munaron (Raineri/Fiat), Lorenzo Bandini (Volpini /Fiat), René Abbal (Stanguellini/Fiat) and Roberto Lippi (Stanguellini/Fiat) prepared for the challenge on the ice.

The fight for the lead in this heat was less intense than in the first, with Laureau quickly opening up an elastic advantage over his competitors, without being threatened at any point in the race. But at the back it was a different story, with Bandini, Lippi and Munaron fiercely competing for 2nd position.

Taking advantage of the opponents’ small mistakes (there were plenty of them in the slippery track), overtaking was not such a difficult task, and the lead in this small group changed regularly. In the end, the one who did best was Munaron, who crossed a second ahead of Bandini to secure second place, but with almost 40 seconds deficit for the first place Laureau.

The first racing session in Cortina d’Ampezzo thus came to an end. Of these first 2 heats, only the two winners (Mathé and Laureau) had classified themselves to the semi-finals of the event. Meanwhile, the other 12 drivers were now preparing to compete in the repechage, which would be the first step before the final of the Corsa Sul Ghiaccio. This would also be made up of 10 laps.

Repechage 1 featured the fastest riders from the first 2 heats – and even though a good battle for the lead was expected, it didn’t happen. This was largely due to the difficulty that pilots were finding in driving close together in the snow, as such movement involved many risks. The one who stood out was Nino Crivellari, who was the first to cross the checkered flag, with a time of 10min28s5″. Close behind were Carmelo Genovese and Gino Munaron, in second and third respectively.

Repechage 2 basically followed the same plot as the first, only this time with an even more dominant performance. After 10 laps, Corrado Manfredini had managed to build an advantage of more than 45 seconds over De Carli, who was his closest pursuer. And, with the exception of De Carli himself, all the drivers had been lapped at least once by Manfredini, such was the Italian’s dominance in the Cortina ice.

Due to the shorter periods of sunlight in the height of the European winter, in addition to the geographical condition of the Cortina valley, there was no longer enough visibility to carry out the remaining races (semi-finals and the grand final) and it was only the following day that the activities would be summarized. This short break was used to catalog the race times, as well as being an opportunity to make small repairs to the circuit.

As the 18th emerged on the horizon, it was another mild day in Cortina. As soon as the drivers arrived at the circuit, they prepared for the semi-finals, which would last 12 laps each. Semifinal 1 would feature some of the fastest drivers from the previous repechages, in addition to Mathé and Laureau, who had qualified in the first races. So, out of this total of 8, only the best four would go directly to the final.

Unsurprisingly, the heat was dominated by the ‘Fetzenflieger’ and the ‘Monomill’. Throughout all the laps, Laureau always threatened Mathé’s lead, but the Austrian remained firm in his place, without giving in to the pressure of the Panhard. Just behind, a battle between two Scuderia Madunina cars entertained the public: the Mille Miglia veteran Giovanni Alberti was competing for third place with the FJ rising star Lorenzo Bandini.

The duel between the two Italians lasted until almost the final laps of the race, until Alberti finally managed to open up an advantage of just a few seconds over Bandini’s Volpini. But nothing that discouraged the young Lorenzo, who knew that fourth place was enough to qualify him for the grand final of the ice race.

However, both Alberti and Bandini could only watch as Mathé crossed the finish line 40 seconds ahead of the Italian duo. The closest driver to the winner was Laureau, who after trailing Mathé throughout the race, finished 3 seconds behind the Austrian’s sleek silver car.

Semifinal 2 would theoretically follow the same scheme, with the remaining drivers from the repechage competing for 4 more places in the final. But, due to retirements, mechanical problems and withdrawals, the four drivers who did not qualify in the first heat were invited to join the grid again. It was a second chance, which could not be wasted.

And some drivers took advantage of this opportunity: both Nino Crivellari and Carmelo Genovese, who had placed sixth and eighth (respectively) in the first race, achieved better results in the second, finishing in the 2nd and 3rd positions. De Carli, who was one of the few original pilots scheduled for this second heat, had also managed to perform well, securing the last spot in the final with his fourth place. The big disappointment was the 1958 Formula Junior champion, Roberto Lippi. The Italian had two miserable races, finishing in the 7th place in both, being well below the standard of performances that had propelled him to the category title the previous year.

On the other hand, the undisputed highlight (once again) was Corrado Manfredini. The Italian looked like he was in a race of his own, as he simply destroyed the competition. He was the only one in the battery to complete the 12 laps, having overtaken all his opponents and leaving them as simple stragglers on the track.

Once again it was clear that Manfredini’s Wainer seemed to be the only Italian car capable of challenging Laureau’s French Panhard and Mathé’s German Porsche/Volkswagen. So, the fate of the trophy from the first Formulas race in Cortina was in the hands of the Veneto driver: would it stay on Italian soil or not?

But this answer could only be answered on the track. 8 cars lined up in the final race of the Gran Premio di Cortina d’Ampezzo, with Mathé’s ‘Fetzenflieger’ and Manfredini’s Wainer sharing the front row. Close behind was Laureau, followed by the army of Stanguellinis of Alberti, Crivellari, Genovese and De Carli, in addition to Bandini’s Volpini.

Now, the number of laps to be raced around the small Campo di Sopra circuit had risen to 15! A great show deserved a great ending, the organizers thought. Right at the start, Manfredini had better traction in the snow, gaining a small advantage that was essential in taking the first corner. Positioning the car ahead of Mathé’s Volkswagen/Porsche, Manfredini was able to choose the best route, blocking path where the Austrian driver’s Frankenstein car had the biggest advantage: in the curves.

Further back, Laureau didn’t want to take any risks, and made sure to secure third position before thinking about attacking. And, as the laps went by, it seemed that the Panhard was getting further and further back, with the duel between Manfredini and Mathé being the one that would decide the fate of the race.

But it wasn’t just in the front that entertainment was guaranteed. Alberti, Bandini and Crivellari, all drivers from Scuderia Madunina, made a very interesting presentation to the Italian public. Even though they were only competing in intermediate positions, this seemed like something secondary for the trio, who were trying to have fun on the circuit.

The best of the three was Giovanni Alberti, who held off Bandini’s pressure throughout the race. Meanwhile, Corrado Manfredini began to pull away from Mathé, slowly managing to gain an advantage of seconds over his pursuer. And this time increased, as the stragglers hindered the Austrian driver more than the Italian.

On the final lap, Corrado was already 12 seconds ahead of Mathé – he simply had to take the car to the finish line. And so the Italian did, taking the checkered flag and winning the Gran Premio di Cortina d’Ampezzo. In addition to the trophy and the right to declare himself as the first winner of a Formula race on ice in Italy, Corrado Manfredini had set the track record, with a lap time of 43s2. It was complete domination of the driver and his Wainer-Fiat.

Final Considerations About The GP Of Cortina D’Ampezzo

In the wake of the 1959 race, good lessons could be learned by the organizers. Firstly, ice racing, despite its peculiarity and novelty, had been a success, accomplishing the initial main objective, of becoming a distinguishing feature of Cortina. Even though it did not achieve the aim of attracting more tourists, who would only come to see a race, the acceptance of the local public was more than enough to compensate for this small setback.

Because of this, it was agreed that the race would return for a second year, as the II Corsa Sul Ghiaccio A Cortina d’Ampezzo. More than 30 entries were accepted for the 1960 race, with some names that competed in the first edition returning to Cortina after a year’s absence: among these were Zanarotti, Genovese and Bandini, as well as the winner of the 1959 edition, Corrado Manfredini. In addition, other drivers also came to prove themselves on the ice of the Alps, such as the young Italian promises Renato Pirocchi and Giancarlo Baghetti.

But, in the end, none of these names took home the trophy from the 1960 race. After another confusing series of heats and qualifying races, the one who came out on top was the German Heinrich Maltz, in a Hartmann-DKW.

Unknown to everyone at the time, this event marked the end of the ephemeral existence of Corsa Sul Ghiaccio, which would not come back to Cortina in 1961. The 1960 race did not have the same euphoria as the 1959 edition, because despite attracting more entries, was not a success with the public, even with the local audience. Furthermore, the increasing costs of Formula Junior were beginning to make it unfeasible to hold smaller events in the discipline – something that would prove fatal for the sustainability of the category in the following years.

Acknowledgements:

- The FastLane: https://www.the-fastlane.co.uk/formula2/FJ59_1.htm

- EpocAuto Magazine: edition of June 2020

- Auto Sport Italiana: edition of February 1959

- Special thanks to the C’era una volta Cortina Facebook page and its contributors, who provided me with several photos of the event