On 28 September 1977 the Mercedes-Benz star shone at its brightest outside the Sydney Opera House: Andrew Cowan and Tony Fowkes and their teams had won the London to Sydney Rally, both driving Mercedes-Benz 280 E (W 123) saloon cars. Two more of the Mercedes-Benz vehicles were among the top ten finishers. Alfred Kling and his team achieved sixth place with their Mercedes-Benz 280 E and Herbert Kleint’s crew came in eighth in a similar vehicle.

For the 123 model series, the rally was proof both of the cars’ sporting endurance and performance and their comfort and reliability. This was a point emphasised by the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG at the time, Dr Joachim Zahn, at the victory celebration in Stuttgart in 1977. The 123 series was launched in 1976 and remained in production until the beginning of 1986. It was available as a saloon (W 123), a coupé (C 123) and an estate (S 123), and also as a chassis base for special bodies.

From Opera House to Opera House

The start of the marathon 40 years ago was the overture to an event of operatic proportions: 69 cars set off from Covent Garden Opera House in London on 14 August 1977 to compete in the toughest rally in the world, with the teams needing to cover well over 30,000 kilometres across three continents in 30 days and nights. Three sea crossings were also on the agenda. The finish line of the 1977 Singapore Airlines London–Sydney Rally was situated at another famous music venue on the opposite side of the world: the Sydney Opera House in all its architectural splendour.

This rally revisited the concept of the first London to Sydney Marathon, which was held in 1968 and also won by Andrew Cowan, but the second incarnation of the rally, organised by the British entrepreneur Wylton Dickson, was significantly longer and even more demanding than the first. It was publicised in 1976 as “the longest car rally in history”.

A total of six teams took part in the rally in Mercedes-Benz 280 E saloons. They were not officially registered as works teams but were given substantial support from the manufacturers under the direction of engineer Erich Waxenberger.

Car number 27: Herbert Kleint, Günter Klapproth, Harry Vormbruck (Herbert Kleint, private entry)

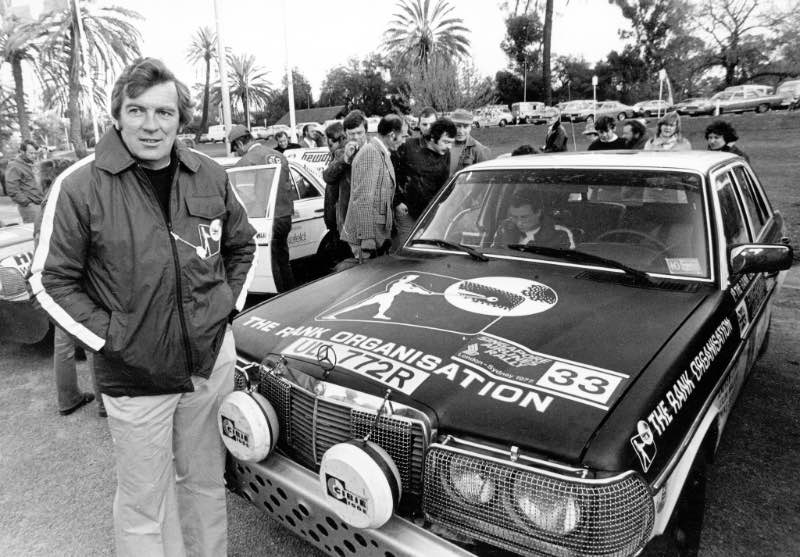

Car number 33: Andrew Cowan, Colin Malkin, Michael Joan Broad (Rank Organisation team)

Car number 37: Joachim Warmbold, Jean Todt, Hans Willemsen (Joachim Warmbold, private entry)

Car number 49: Anthony Fowkes, Peter O’Gorman (Johnson Rally Wax team)

Car number 59: Alfred Kling, Klaus Kaiser, Jörg Leininger (Alfred Kling, private entry)

Car number 80: Wolfgang Mauch, José Dolhem (Wolfgang Mauch, private entry)

Meticulous Preparation

In 1977, Mercedes-Benz’ major successes with near-standard works rally cars lay some time in the past. Nevertheless, Erich Waxenberger followed the recipe for those bygone successes characterised by the winning tail-fin saloons and standard production SL models. Eight different Mercedes-Benz test departments were involved in readying the 280 E for rally use (including bodyshell, brakes, engines and overall vehicle) as well as central customer services.

The saloons were fitted with new wheels (15-inch), plus sport shock absorbers and so-called tropical springs — both of which were available as optional equipment items. These measures combined to raise the cars’ ground clearance by 35 millimetres. Then, after test drives on the British Army training grounds in Bagshot, it was also decided to reinforce the upper and lower sections of the semi-trailing arms.

In place of the standard gearbox, the rally cars were fitted with the four-speed manual gearbox from the V8 engine used in the S-Class (W116) of the time. An addition was the robust sand plate mounted at the front in place of conventional bumpers. In order to facilitate servicing and the supply of replacement parts, both British teams drove left-hand-drive vehicles.

Even the quality of the fuel supplied along the route was factored into the planning: as the octane rating of the available fuel was liable to be as low as 82 RON, the vehicles’ ignition was specially adapted. The drivers also carried a canister of octane improver with them, with an auxiliary fuel tank in the vehicle allowing high-octane fuel to be mixed into the local petrol.

Tony Fowkes described his personal equipment in an interview with the weekly magazine India Today in September 1977: along with spare parts for the car, other essential items included malaria drugs, insect repellent, water purification tablets and toilet paper — as well as fruit and Kendal Mint Cake.

Service Network

The rolling support points implemented by Mercedes-Benz covered the entire route of the London to Sydney rally: the Stuttgart-based brand set up bases in Milan, Trieste, Veria, Lamia, Athens, Istanbul, Ankara, Kayserie, Mus, Van, Tabris, Teheran, Yazd, Tabas, Fariman, Kandahar, Kabul, Lahore, Delhi, Ajmer, Baroda, Bombay, Belgaum, Bangalore, Madras, Penang, Singapore, Perth, Alice Springs, Adelaide and Melbourne. Additional back-up was provided by support vehicles accompanying the rally. Mercedes-Benz provided a 280 E as a service vehicle from Persia to India, driven by Erich Waxenberger and Joachim Tilgner. In Australia, where the rally had to cover long desert stages, Mercedes-Benz brought in a Unimog.

At the victory party, Daimler AG Chairman Zahn highlighted the partnership and collaboration the drivers had enjoyed from the global Mercedes-Benz network during the rally and beyond. He underlined the point that the experiences gained from the rally could provide valuable information to feed into series production development at Mercedes-Benz. For the Stuttgart brand the London–Sydney success story marked the beginning of a new era of rally involvement, the highlights of which included successes with various SLC Coupés of the C 107 model series in South America and Africa from 1978 to 1980.

The original winning car from 1977 is on permanent display at the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart. It is part of “Legend Room 7: Silver Arrows – Races and Records”.

[Source: Daimler AG]