Words by Lorenzo Baer.

When the subject of Formula 1 comes into discussion, it is undeniable that people immediately think of the great teams and manufacturers that helped to shape the history of the category: Ferrari, McLaren, Williams, Lotus, Cooper, Brabham and so many other legendary names, who, through the ages, have built their legacies, made their contributions or actively participated in the process of technological development, which has always been the hallmark of F1.

Despite all these names taking the spotlight, a large portion of the category’s history is made up of its most peculiar, strange and even dubious characters – those who, alongside the “giants”, provided some of the sport’s most interesting moments. For example, how can we not talk about F1 in the 90s without remembering infamous teams such as Andrea Moda, Life and Lola-Mastercard, which, through their poor performances, became symbols of what not to do in the category.

On the other side of the spectrum, we have RRC Walker, which to this day is recognized as one of the most successful privateers in the history of the category, achieving victories with cars from 4 different brands (Connaught, Cooper, Lotus and Brabham). Same is the case with Tyrrell, which initially acting as a privateer, became one of the best-known teams in the history of F1, due to its meteoric rise and desire for innovation – which often went too far.

These last two cases highlight the great contribution (often forgotten) that privateer teams have had in the historical context of F1. Although failures are much more numerous than successes in this category, the determination, ambition and creativity of many of these wild entries was something of a constant presence on the F1 grids. They were certainly the substrate that held this F1 together in its definitive transitional moment, leaving behind the final remnants of amateurism that still lingered in the paddocks at the end of the 70s.

The playful environment, which had once been part of the category, was lost forever, as technology pushed those who no longer belonged to this ‘new F1’ to the sides of the field. However, the last act of the ‘classic Formula 1’ would only take place in 1987, in what would become recognized as the last attempt at private entry on the category’s grids: its name was Middlebrigde-Trussardi – the last of the rest.

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE PRIVATEERS IN F1

Before talking about Trussardi’s (mis)adventure in F1, it is worth mentioning some of the most important moments in the history of privateers in Formula 1 – a relationship that has its origins well before the category itself, when motorsport depended almost exclusively on passion and dedication of those who made up their ranks, with success or failure in a race being decisive in paying the bills. Even though facing direct competition from the big teams of the time (such as Mercedes, Delage, Bugatti and Alfa-Romeo), it was not uncommon for some drivers to achieve notable victories for their CVs in these days of pioneering motorsport: for example, a still unknown Rudolf Caracciola was the first to put his name in the history of the German Grand Prix, winning the very first edition of the race in 1926, with a private-owned Mercedes M72/94.

Another important milestone in this early history of customers was undoubtedly the victory of William Grover-Williams, aboard his recognizable green Bugatti T35B, at the 1929 Monaco GP. Despite all those entered in the race being privateers (which consequently meant that a privateer would win the race), it was the Briton who opened the lineage of Grand Prix winners in the Principality, with a car and team entirely belonging to the driver.

However, it was in the post-war years that the phenomenon of privateers became more serious, since, with the centralization of the main GPs under the auspices of the F.I.A., a greater commitment was needed to face the increasingly professionalized works-teams and other factory-backed efforts. This unification certainly privileged the official squads, which dedicated themselves to the maximum in competing for not only the drivers’ championship, but also the constructors’ championship (which came into force in 1958).

A clear consequence of this transition was that the support of the big brands for some more successful customers slowly faded away, causing them to become increasingly distant from their parent manufacturer companies/suppliers; until the point that almost no relationship existed, with both private and constructor acting independently of each other. Because of this, successes in major GPs for these small teams began to become increasingly scarce, with only small victories registered in the various non-championship races that complemented the regular Formula 1 championship.

A great example of this can be the case of Gilby Engineering Ltd., just one of the dozens private entries that populated the F1 grids in the 50s: the best results the team achieved in the official F1 championship events were a handful of abandonments and poor performances. However, in the same period (between 1954 and 1956) the Gilby team had collected 5 victories in non-championship events, thanks to brilliant performances by Roy Salvadori.

Perhaps the great exception to the rule between the 50s and 60s was the Rob Walker Racing Team (later known simply as RRC Walker), which would be the epicenter of what would be known as the ‘golden age of privateers’. Aligning competitive equipment (such as Coopers T51 and Lotus 18) with one of the most competent drivers of its time (Stirling Moss), the team has provided perhaps the biggest success story for a customer to that date: 8 victories in championship events, in a space of 4 years (1958-1961).

However, it would be a few years before the 9th trophy was added to this collection; In 1968, Jo Siffert would snatch the last major victory for the Walker team – the last for the great F1 privateer.

But certainly, the climax of the history of adventurers in Formula 1 would be the year 1969: Tyrrell, with its French-built Matra chassis, would become the first team to definitively achieve something with a product not built by the team itself. If before the fight between the privateers and the factory teams was for victories, Tyrrell would take this confrontation to another level, positioning itself as a potential contender in the fight for the category’s overall title. And history would truly be written by Ken Tyrrell, Jackie Stewart & Co., with the British team becoming the first F1 World Champion with a third-party chassis.

Tyrrell’s success proved unique in the history of Formula 1, with the team (seeking to remain at the top) transforming itself into a car manufacturer, after years of dependence on Matra and, later, March. What the team demonstrated in practice was something that had already been felt since the transformation of privateer paper in the 1950s: large automakers would never supply their best material to third parties; and, in the exceptional case of Tyrrell in 1969, such success happened only due to the strong support of Matra, which transformed Tyrrell into a “quasi-semi-works” teams, getting really close to get the official works status.

Throughout the 70s, the privateer phenomenon slowly faded away, with the last competitive customers giving the final tones to this story: Frank Williams Racing Cars, with its March, between 1971 and 1972; the South Africans Team Gunston and Scribante Lucky Strike Racing, with their second-hand Lotuses 72s; or Hesketh Racing, in 1973, which with its March 731, achieved some good results, with a young James Hunt at the wheel. However, it is worth noting how two of these teams (Williams and Hesketh) later became constructors, following in the footsteps of Tyrrell.

Attempts to keep privateers on the grid were made until the end of the 70s, with some very peculiar figures being responsible for these appearances. For example, in 1979, the only customer on the grid would be the Mexican Hector Rebaque, with his Lotus 79. In 1980, Rebaque was replaced by RAM/Penthouse, which, lining up a couple of one-year old Williams FW07, competed in seven stages of the F1 world championship (but the team managed to qualify for only four of these).

However, a major milestone would almost put an end to the history of customers and privateers: the 1981 F1 Concorde Agreement, which, in addition to settling the dispute that existed between the two major institutions that managed the category at the time, the Federation Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA) and the Formula One Constructors’ Association (FOCA), stipulated other clauses, with the aim of definitively professionalizing the sport.

Many parts of the agreement directly impacted privateers, who, by nature, were more amateurs than professionals. Taking into account the 1997 version of the agreement (the only version of the agreement that was made public to this date – 2024), it is clear how the F.I.A. and FOCA sought to definitively ward off this type of wild-entry, qualifying as applicable for the races only teams that built or had exclusive rights to use a chassis.

But, as mentioned previously, this would be a case of “almost”, as the final chapters of the story were yet to come. The first would be the one written by Emilio de Villota, between 1981 and 1982. The Spaniard, who had been champion of the Aurora AFX in 1980 (the British F1 championship, which was mostly contested by F5000 spec cars, plus some old and second-hand F1 vehicles) had decided to participate in his own national Grand Prix, with an old Williams FW07.

Despite the pilot participating in the training sessions and obtaining, due to a loophole in the regulations, the F.I.S.A., F.I.A. and the R.A.C.E. (Real Automovil Club de Espana) approvals to participate in the race, at the last minute, the driver was banned from racing in the Spanish GP. This was due to the fact that F.I.S.A. reviewed its initial decision, claiming that if Villota aligned in the grid for the race, the Spanish GP would be disregarded as a valid stage for the F1 world championship – a threat to which the R.A.C.E. didn’t want to pay to see it.

However, Villota would not give up, and in 1982 he would officially become the last privateer to attempt to qualify for a Formula 1 race, with a March 821. Despite acting as an almost semi-works for March, it was clear that the Spaniard acted more as an independent than as someone linked to the English car manufacturer – see the car’s paintwork, which contrasted sharply with the works cars; or the team of mechanics, which had nothing to do with those who worked for the factory-backed team.

To give greater emphasis to this differentiation between the two teams, Villota’s car ran under the LBT Team March badge; in contrast, Jochen Mass, Rupert Keegan and Raul Boesel, who were the official drivers for the March team, were all registered as drivers for Rothmans Racing with March Grand Prix. Despite his boldness, Villota ended the story of privateers in F1 in a melancholic way: 5 entries, without being able to qualify for any of them.

But the last part of this story was yet to be told, when in 1987, a rumor broke that a new privateer was about to join the category. When the details started to emerge and the story began to gain volume, it seemed that finally a customer could make a difference on the grid again, presenting a very promising mix: a proven winning chassis, a driver with enormous potential and some economic power in the background. And so begins the ephemeral story of Trussardi in F1….

A DREAM CALLED MIDDLEBRIDGE-TRUSSARDI

The origins of Trussardi’s interest in joining the F1 circus were mainly due to the successes that another clothing manufacturer was having in the category: Benetton. Since 1983, initially as a sponsor of the Tyrrell team, then migrating to Alfa-Romeo and then Toleman, the clothing manufacturer from Ponzano had been gaining ground in the market, transforming itself into a global pop phenomenon until the mid-80s.

Successes on the track fed back into the company’s commercial success, in a symbiotic way. So, when Benetton became an official constructor in 1986, a whole new situation shook the company, with the clothing brand definitely linked to the image of cars in F1. And the team’s first victory, at the 1986 Mexican GP, was the cherry on the top of the cake, catapulting Benetton’s image to the world, going beyond its nominal meaning as a clothing brand to become an integral element of the sport.

By carefully observing the case of success of its compatriot brand, Trussardi started to draft plans for a similar enterprise, which would closely follow Benetton’s footsteps. In the same way as Benetton, Trussardi planned to enter the category in partnership with an already established team in the automotive scene, using this company’s know-how as a way of getting the necessary knowledge to participate in a F1 race. Plans to act as an independent constructor were not discarded for a distant future, but at the first moment, the important thing was to get inside the Formula 1 circus.

This undertaking began to take on more physical contours in the European spring of 1987, when Luciano Secchi, an experienced sponsorship negotiator within F1, began to mediate the first conversations between Bernie Ecclestone, at the time, chief executive of FOCA and also main actionist of FOPA (Formula One Promotions and Administration), and the Italian brand. From this first contact, Trussardi’s possible entry into Formula 1 began to be outlined – but there was a problem: which car or team to sponsor?

Initially, an agreement was considered with the Arrows team, which was looking for a minor sponsor to complement the income of the United States Fidelity and Guaranty Company (USF&G) – the team’s primary patron for 1987. An agreement was reached between both parties to take effect beginning on the British GP, but the contract fell through (this without before the Arrows cars showed up for this GP training sessions with Trussardi sponsorship markings on their engine covers).

At this moment, the side B of this story appears, made up of Middlebridge Racing, a small English team based in Nottingham. Initially founded as a manufacturer of civil sports vehicles, Middlebridge opened its racing department in 1986, with the intention of participating in the British Formula Ford 2000 championship. The team officially entered the category only at the beginning of the following year, and quickly proved itself a sensation in FF2000: two victories achieved at the beginning of the year, in Snetterton (26 April) and Brands Hatch (10 May).

Both of these triumphs were achieved by John Alcorn who, alongside Paul Warwick (younger brother of the F1 driver Derek Warwick), formed the team’s roster of drivers for the FF2000. The team was served by two Reynard 87SFs, which were the best cars available in the category – so it was not surprising at all that Alcorn and Warwick managed to collect other good results in the FF2000 races.

Buoyed by its success and the self-confidence of its owner, Kohji Nakauchi, Middlebridge began to flirt with the possibility of taking a giant step: of entering as a team in the increasingly restricted circle of F1, in some selected stages of the championship. The team’s main objective for the year would be to provide a Japanese driver with the opportunity to race in that year’s Japanese Grand Prix (which would be contested only in November), competing for a Japanese-flagged squad – despite the fact that the Middlebridge Racing was obviously a British-based team.

But, for all this to happen, the team first needed a car. To this end, Kohji delegated to John Macdonald, who at the time, already accumulated the role of team leader of the FF2000 project, the task of finding a Formula 1 vehicle that was already duly approved to participate in the category. Well, since an F1 car is not a vehicle that can be found in any dealership or scrapyard, Macdonald began approaching the F1 manufacturers themselves, looking for vehicles considered “surplus” by these squads.

Incredible as it may seem, Macdonald finally found a constructor that was interested in selling some old F1 machines to Middlebridge – and, by some coincidence of the destiny, it was Benetton itself.

The anglo-italian team was tempted by Middlebrigde’s proposal, in an agreement that seemed to be beneficial for both parties: while Benetton would get rid of some vehicles that no longer had use, obviously gaining good financial compensation from the agreement, Middlebridge would have its demand met, receiving a fine product – to be honest, above the initial expectations of the team. Ultimately, the deal was sealed, and Benetton sold two of its old B186s (used in the 1986 season) to Middlebridge, sometime around mid-May 1987.

It was at this point that the stories of Middlebrigde and Trussardi converge, with both finding the means, in each other, to achieve their goals: a new team is always looking for new investors – and, when the news of Trussardi’s supposed interest in joining F1 reached the ears of Kohji Nakauchi, the Japanese businessman was quick to secure a lucrative deal with the Italian designer brand.

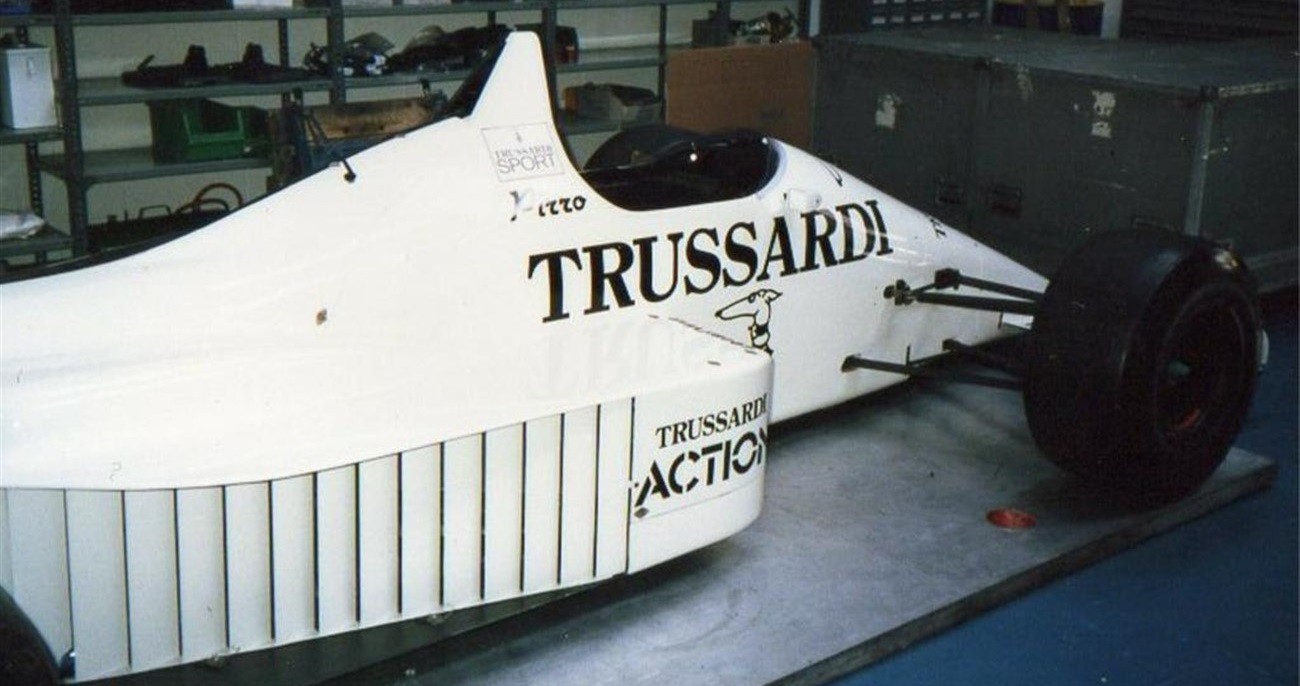

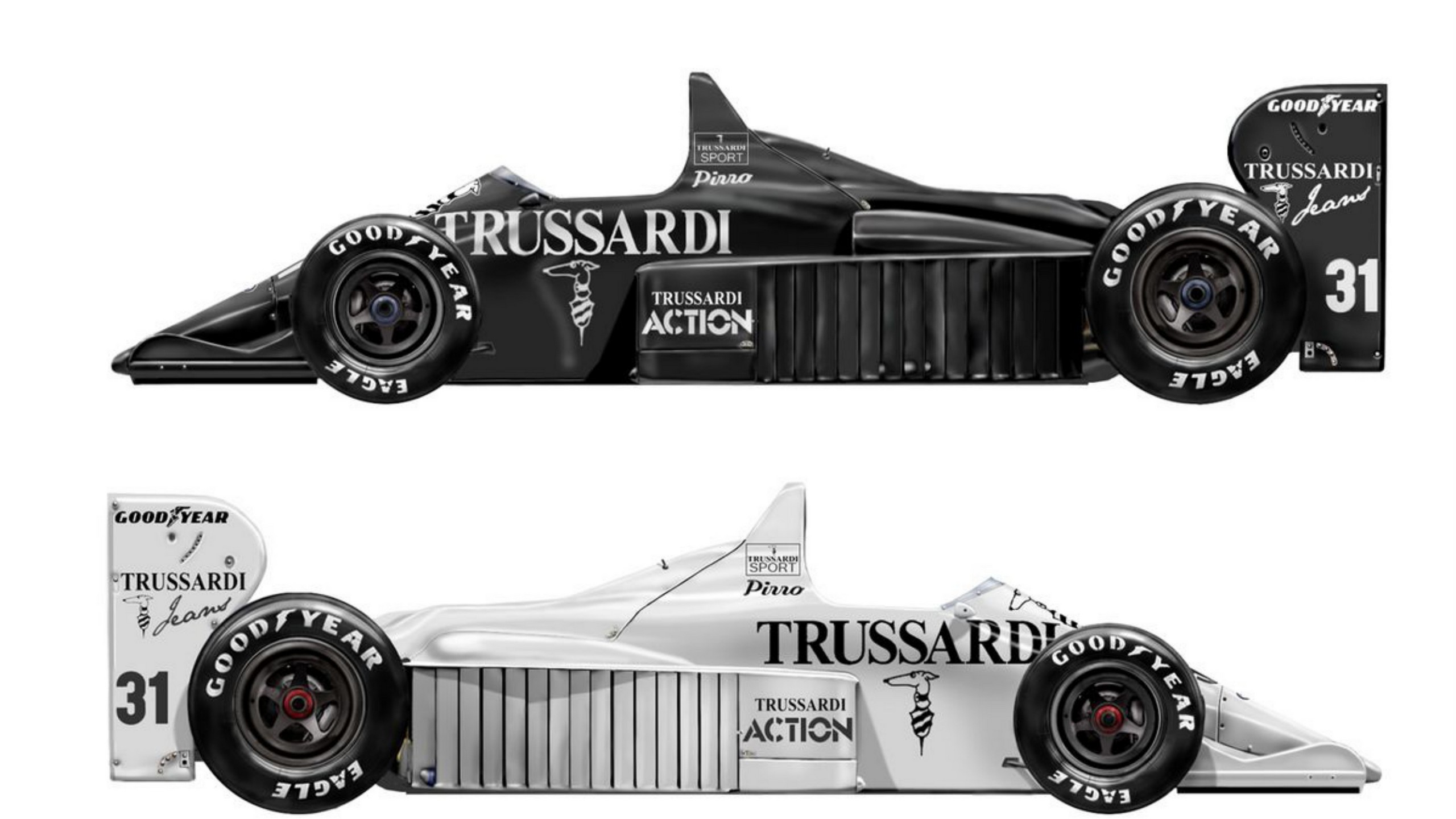

Thus, when the cars were officially revealed to the rest of the Middlebridge Group’s board of directors, in June 1987, the B186 had already acquired its new look: the bright colors of the vehicle’s former owner had given way to a more discreet palette based on black and white, the symbols of the Trussardi brand. Though, there was a catch: the peculiar characteristic of the car paint was its asymmetrical pattern, with the left half of the car being dominated by black, while the right would be mostly white (a paintscheme similar to the 1999 F1 BAR cars).

Even though everything seemed to be going well in terms of aesthetics, in terms of mechanics there was still some discussion going on: initially, it was expected that the B186s would be re-engined with HART engines, replacing the vehicle’s original BMW powerplants. The change was expected to reduce the vehicle’s operating costs, as the BMWs were much more complex and expensive than the British-made HART.

Although this line of thought prevailed among the team’s mechanics, in the end the decision belonged to Kohji, and he decided to retain the BMW engines, in order to provide the future Middlebrigde-Trussardi drivers with equipment that could be competitive in race situations.

This decision would end up not going down well with other teams on the grid, who were now starting to take Trussardi’s proposal more seriously. The main problem was the real threat that the team now offered, with a privateer counting, after decades, again with some state-of-the-art material; certainly, the one-year-old B186s would not be a car to compete for victories, but they were certainly vehicles that had a good chance of constantly reaching the top-10 of races.

Even so, the project continued forward, with the team signing contracts with some motorsport promises, such as the Italian Emanuele Pirro and the Japanese Aguri Suzuki, who would drive for Middlebridge-Trussardi in the selected stages that the team wanted to participate in. In gross lines, Pirro would be the team’s main driver, while Suzuki would be the pilot who would complete the ‘Japanese objective’ – that is, being contracted solely and exclusively for the purpose of competing in that year’s Japanese Grand Prix.

Two months went by before the team finally felt ready to participate in a GP. Middlebrigde-Trussardi’s first attempt to enter an F1 race was the Austrian Grand Prix, which was to be held on August 16th. In the meantime, provisional agreements had been signed with several suppliers, the most important of which was the contract with Pirelli, with the company committed to supplying tires to Trussardi during the rest of the season.

However, hand-shakes and resourcefulness alone were not enough for Middlebridge-Trussardi’s dream to truly become a reality. The last step of this journey was beyond the control of Macdonald and Nakauchi, who now found themselves hostages to the F.O.C.A. and the teams’ verdict, to decide whether Trussardi could actually join the F1 circus. Obviously, after submitting its application, the team would have to wait some time before a definitive answer to the case was given.

So, John Macdonald waited, waited and waited, for a response that never came – until it was too late for the team to leave in time to take part in the Austrian GP. In the end, Trussardi had finished what should have been its first race weekend in the same condition as it started that week: in its garage at Nottingham, the same place the team had been quartered for three months, since receiving the B186s.

To avoid a repeat of the same failure in the next GP (which would take place in Monza, less than one month later), John Macdonald began to draw up a plan, which mainly sought to gain the support of a few F1 teams so that Middlebridge would have its registration guaranteed in Italy. Although some squads welcomed the inclusion of the team on the grid, as long as some conditions were accepted (such as the rebadging of the team’s cars, which would no longer be called Benetton B186, but actually Trussardi B186), once again the ideals were supplanted by established interests and rules.

Despite the re-registration of cars, it was undeniable that the Trussardi B186 clearly violated the F.I.A.’s rule that no constructor could have more than 3 cars on the grid (the only exception to this rule is with fewer than 16 cars registered in a race when, by contractual obligation, teams are obliged to line up a third car).

Another point that slowed Middlebridge-Trussardi’s entry into F1 was the imminent renewal of the Concorde Agreement, which would expire at the end of 1987. Many teams avoided taking any more radical action (such as talking about the possible inclusion of a privateer in the category), with the fear that this could cause a backlash when the new contract was signed.

In particular, the teams with great power in the category, like Ferrari, McLaren, Lotus and Brabham (still owned by Ecclestone), sought not to back Trussardi’s claim, since they were the ones with more to lose, if a feud arise from the Middlebridge-Trussardi/FOCA problem.

The final nail in the team’s coffin was when BMW was involved in this process, due to the allegation that Trussardi was using the brand’s equipment without its consent, refusing to provide the team the Engine Control Unit (ECU), something that would be essential to set the BMW (Megatron) M12/13 engine in the correct parameters for races.

Without support from the German automaker, the project was truly doomed to failure and Middlebrigde-Trussardi had nowhere else to go. Vain attempts to enter the B186 in the remaining GPs of the season were made, with a resolute ‘NO’ being the answer in all cases.

Despite never getting close to a racetrack, Middlebridge-Trussardi can boast the title of being the last true privateer to sign up for a F1 event. It was a melancholy end to an aspect of the sport that had contributed so much to the development of the category since its embryonic years – but these were the new times: the era of dreamers and amateurs had come to an end, with professionalism being the hot ticket in F1.

MIDDLEBRIDGE: A NEW BEGINNING…AND A NOT SO NOBLE END

After its failed attempt to enter F1, Trussardi and Middlebridge parted ways, with the clothing brand looking to move away from its F1 misadventure as quickly as possible. Middlebridge also decided to take a step back, regressing again to the British motorsport grassroots scene.

After also ending its activities in FF2000, the team decided to participate, in 1988, in the British F3 championship, with three drivers: the team’s veteran, John Alcorn, the other British member of the trio, Phil Andrews, and the Belgian Arnaud Guiot (who participated intermittently in the championship). They all drove Reynard’s 883, and a few occasional successes were enough to considerably improve the team’s image after their 1987 adventure.

Also in 1988, Middlebrigde also participated in the Japanese F3000, in a partnership with the Team Le Mans. Managing to retain Emanuele Pirro for this venture (after a generous offer to the Italian), the team fared reasonably well: Pirro finished third in the general standings, achieving two second places and a third throughout the season.

In the following years, Middlebridge once again expanded its operations; only this time, in a much more conscious and sustainable way, with the team dividing its attention between the British F3 and the UK’s F3000 championship, counting with the services of some reliable drivers, the best known of them being Mark Blundell and Damon Hill.

However, the end of Middlebridge Racing was quickly approaching on the horizon, as the team went through a serious financial crisis in late 1992. This was due a series of factors, including Kohji Nakauchi (who still owned the company despite the failure of ’87) purchase of the legendary team Brabham in 1989, thus finally materializing the businessman’s dream of having his own F1 team; however, this decision would prove to be fatal, condemning both teams to a terrible end for their stories.

The biggest problem was that less than three years after the Brabham buyout, financial embezzlement and fraud investigations ended up completely shaking Kohji’s empire, which ultimately saw both Brabham and Middlebridge swallowed by this turmoil. When the storm passed, there was no trace left of Brabham or Middlebridge other than their legacies on the track. Both were definitively relegated to the pages of history, as pioneers (each with their own meaning) in a discipline called motorsport.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Middlebridge Enthusiasts Scimitar Set, a selected group which still preserves the heritage of the Middlebridge cars and Middlebridge Racing team