In the week of the Spanish Grand Prix, why not revisit one of the strangest and most peculiar stories of Formula 1 in Spanish territory? The 1969 Madrid GP, which ended up being one of the biggest fiascoes in the history of F1 events. But not everything went so terribly, because one thing saved the race from being a real disaster: the quick support from other categories, which helped to transform the long-awaited and desired F1 event into a great free-for-all.

Non-Championship Races: Relics of the Past

The 1969 season marked the beginning of a new era in Formula 1, encompassing the economic, technological and sporting factors of the category. Starting with the matters of technological evolution, we can say that it was in the final years of the 60s that cars in F1, F2 and other single-seater categories began to resemble the vehicles we see on today’s circuits. The primitive high-wings and ailerons implemented in 1968 gave way the following year to more definitive installations, which put into practice in a more efficient way the lessons learned about car aerodynamics, together with what we know today as ‘ground effect’.

Furthermore, other important trends could be observed in Formula 1 at the end of the 60s, like the exponential increase in levels of professionalism in the category, which served to strengthen the sporting context, but also alienated those who were now considered ‘personae non gratae’ to the increasingly restricted circle of F1.

Perhaps one of these elements was made up of the non-championship races, which were a reminiscence of the times when the category was taking its first steps. At the height of this trend, which occurred mainly between the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s, it was common for there to be around 20 events of this type spread throughout the year.

These events had a dual purpose: on the side of the organizers and promoters, the publicity of a F1 race was excellent, generating a significant return in image and reputation, with a lower cost than the one of an official GP. On the other side of this coin, we have the teams, who were basically forced to participate in these events due to financial pressures.

Coldly analyzing, many (if not all) of the F1 teams of the 60s walked on a tightrope when it came to the financial aspect. Money was a scarce commodity at a time when big sponsorships were still a thing of the future, and almost every source of income came from sporting success on the tracks. Therefore, participating in non-championship races, which often offered prizes almost comparable to those of the official GPs, was an undeniable obligation.

But the introduction of master sponsorships in 1968 was a turning point in this story. From now on, the teams had a more steady and continuous flow of money during the year, not being forced to make calculations based on assumptions of victories in races outside those on the official F1 calendar.

Another reason that led to the disappearance of these races was that many of them were based on the idea “low budget, good prizes”. In other words, safety was just something secondary, as long as a substantial prize was offered to participants. For example, many of these non-championship races took place on public streets or improvised circuits; so, it was inevitable that such events were doomed to disappear, especially at a time when safety has become a watchword in motorsport.

Therefore, the picturesque events that always dotted the early F1 years slowly disappeared, being definitively extinct or migrating to other sub-categories (such as F2 and F3); the few that survived, found their own ways to remain relevant in the increasingly globalized scenario of motorsport.

The most used alternative to maintain or even insert an event of this type in the calendar was to attract entries from different categories. It wasn’t uncommon in non-championship races from 1969 onwards for F1, F2 and F5000 cars to race together, relying on a combination of ballast and limiters to ensure fair competition between the classes.

One of these cases was the III Gran Premio de Madrid. Initially, the race wasn’t supposed to follow this pattern, being idealized as an exclusive event for F1. But, due to disagreements, questions regarding envy and pride, and some minimally suggestive decisions, Madrid would also be the stage for one of these ‘miscellaneous races’ – and in the end, it barely escaped from being a resounding failure!

Why Did The 1969 Madrid GP Happen In The First Place?

The resurgence of motorsport in Spain took place in the second half of the 1960s, with the return of F1 cars to the country after a 13-year hiatus. Initially, it was agreed that Madrid would be the new headquarters of national motorsport, largely due to the modern Jarama circuit, opened in 1967 on the outskirts of the Spanish capital.

But this decision generated a negative impact within the Real Automóvil Club de España (RACE), responsible for promoting the GPs in Spain. The choice of Madrid only served to intensify tensions with its main rival, the city of Barcelona, which now saw itself as just a satellite point in Spanish motorsport.

This scheme was almost inconceivable for Real Automóvil de Catalunã (RACC), because since its inception, in the early 1900s, it was this club that organized the biggest automobile events in the country. One can see that until the construction of Jarama, the main Spanish racing venues (Sitges-Terramar, Pedralbes and Montjuïc Park) were concentrated in Catalunã. Therefore, this change in the balance of power (which involved other political factors) could only create problems.

Due to increasing pressure from the Catalan side, the RACE was forced to review its decision, setting an agreement whereby Madrid and Barcelona would alternate on an annual basis, from 1968 onwards, as venues for Formula 1 races in the country. Even though this seemed to be the best path to take, in the end, this relay turned into an unpopular option, which did not please either side.

So, it is no surprise that, in addition to the F1 trophy, each city continued to maintain its own regional ‘GP’: in the Catalan capital, the Gran Premio de Barcelona (also known as the Juan Jover Trophy) was contested; while in the country’s capital, the Gran Premio de Madrid would take place. Both were originally eligible only for F2 cars, but the alternating scheme in Formula 1 changed this system.

The one who rebelled first was Jarama, who after having hosted the 1968 Gran Prix de España, found itself deprived of its biggest attraction for the 1969 season (since it was Montjuïc Park’s turn to take over the role of hosting the Spanish GP). In no mood and not wanting to wait for the year of 1970 to be able to host the event again, the organizers prepared to promote their own race, without the help of the Real Automóvil Club de España.

Taking advantage of the structure prepared for the Formula 2 race, the O.D.A.C.I.S.A (the group responsible for organizing the races in Jarama) raised the event to Formula 1 standards, optimistically hoping that at least part of the category’s main squads would be interested in the race. And even though some big teams initially showed their intentions to participate in it, such as Lotus and Matra, time went by and none of them presented any concrete offer to appear on Spanish soil. The main problem highlighted by them was the date chosen for the race: 13th April.

On the same day, two other important international meetings would be contested: the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch, a race valid for the World SportsCar Championship, and the Deutschland Trophäe, held at Hockenheim, which was an official points-scoring race for the European F2 championship. Therefore, it is no surprise that drivers and teams chose to participate in these races considered more important, to the detriment of the III Gran Premio de Madrid.

In the end, not even a high prize, like the one promised by the Madrid organizers, could attract names of the size of Hill, Stewart or Courage. Even other drivers from the ‘second shelf’ of world motorsport, such as the New Zealander Graham McRae and the Briton Mike Hailwood, both of whom had agreed to participate in the race, withdrew their entries at the last minute. The excuse given at the time by McRae was that he had problems with his transfer and would not be able to arrive in time for the race in Madrid – meanwhile, the reason for Hailwood’s non-attendance was due to mechanical problems in his Lola T142 – the driver had blown the cars’ Chevrolet V8 engine during the Brands Hatch Easter Meeting (a stage valid for the Guards F5000 Trophy and that took place only one week short of the race in Spain).

Only a handful of drivers had converged on Madrid at the time to participate in the event, with a somewhat peculiar mix of cars. But it was too late to cancel the plans – it was time to race.

The Magnificent 8

By the time the training sessions started in the Spanish capital, only 8 cars had shown up for the contest: 2 Formula 1 cars, 2 F2 and 4 vehicles representing the F5000. The majority of those entries were lesser-known drivers on the world motorsport circuit, but, as always, there were some notable exceptions.

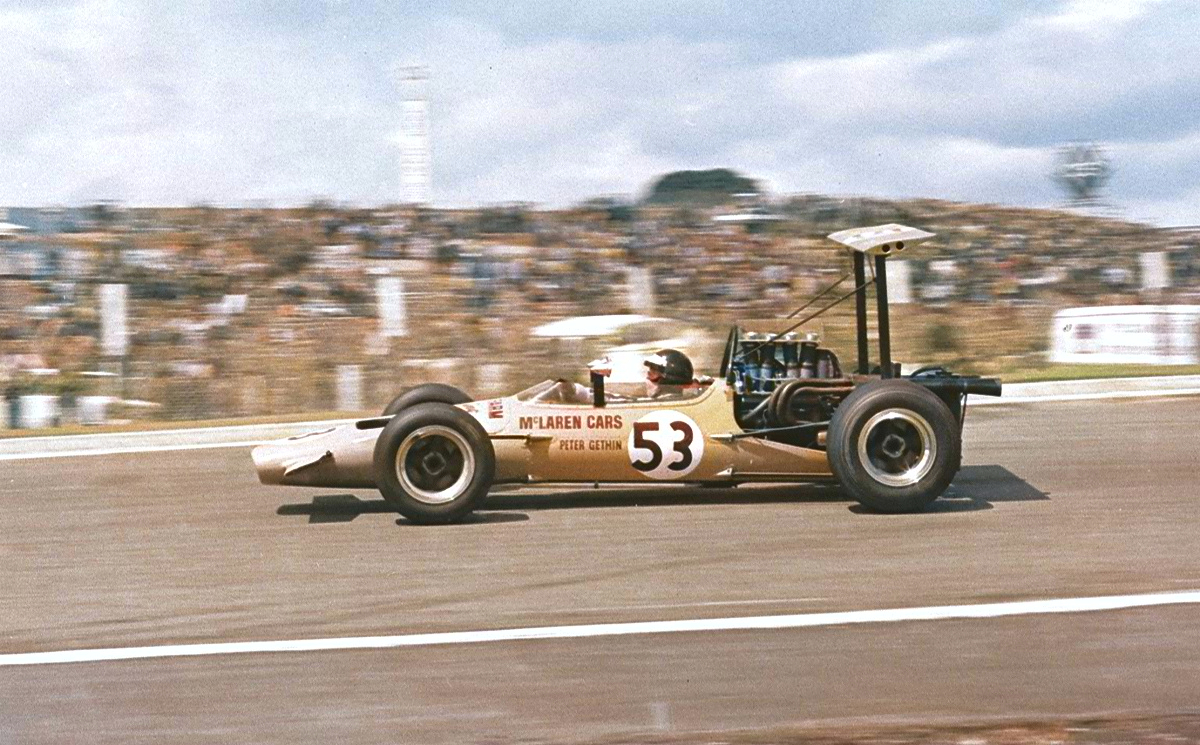

The most recognized name on the entry list may be Peter Gethin, who, in 1969, was still taking his first steps in high-performance motorsport. After a few years in British F3, the driver had moved up to the European F2 championship in 1967. In 1969, Gethin was looking for new opportunities and entered the Formula 5000, the newest European championship for single-seater cars, based on the success of North American Formula A.

As it soon turned out, the Guards Formula 5000 Championship became an absolute success, from both the commercial and sporting point of view, largely due to the quality of the drivers who converged on the series. Amidst names like Trevor Taylor, Mike Hailwood, Frank Gardner and Andrea de Adamich, Gethin quickly stood out, proving his talent against an extremely qualified competition.

For the race in Madrid, the driver would have at his disposal a McLaren M10A (chassis number M10A-1), which was the same car that had given him victories in the F5000 stages at Oulton Park and Brands Hatch, at the beginning of April. The Church Farm Racing, the team that Gethin defended, was nothing more than a semi-works effort of the McLaren itself – therefore, it was to be expected that the car would have some differences compared to its less structured F5000 competitors.

The main one materialized in the engine that thrusted the machine. Even though it appeared to be just another one of the countless V8 Chevrolets that populated the F5000 grids, it had a special touch from Al Bartz, one of the most talented engine tuners of his time. Bartz became known due to his participation in the Traco Engineering Shop, the company that gained an almost mystical tone due to its preparation of Can-Am, Indy, Sports and touring car engines. Therefore, Al Bartz’s association with McLaren was almost an inevitable event, as the New Zealander driver’s company increasingly established itself in the North American racing market.

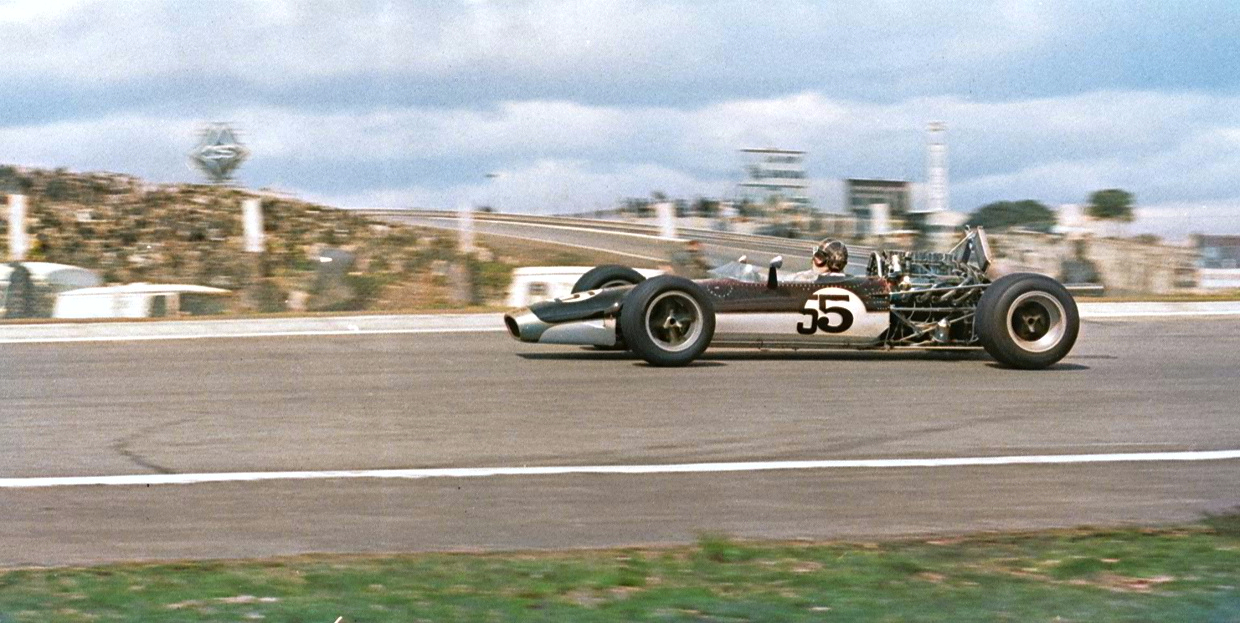

Another appearance worthy of careful observation was of a certain Max Mosley. This name will always attract the attention of anyone passionate about motorsport, mainly due to its role off the track. We can mention his term as president of the F.I.A. for 16 years, his controversial personal life, or even other notable facts, such as his participation in the founding of March Engineering.

Before his fame on the sidelines, however, Mosley was just a simple semi-professional driver, who throughout 1966-68 had participated in several F2 and F3 races. Being part of the squads of the London Racing Team and Frank Williams Racing Cars, the Briton had the opportunity to compete in races with some of the stars that would shine in the tracks during the 70s.

For 1969, Mosley had the ambition to once again prove himself in the increasingly professional and competitive context of F2. Equipped with a brand-new Lotus 59b-Cosworth, the driver hoped that the car would be more than enough to keep him within the pace of his more skilled opponents on the grid. The race in Jarama would be the machine’s first test, proving or disproving Max’s assumptions.

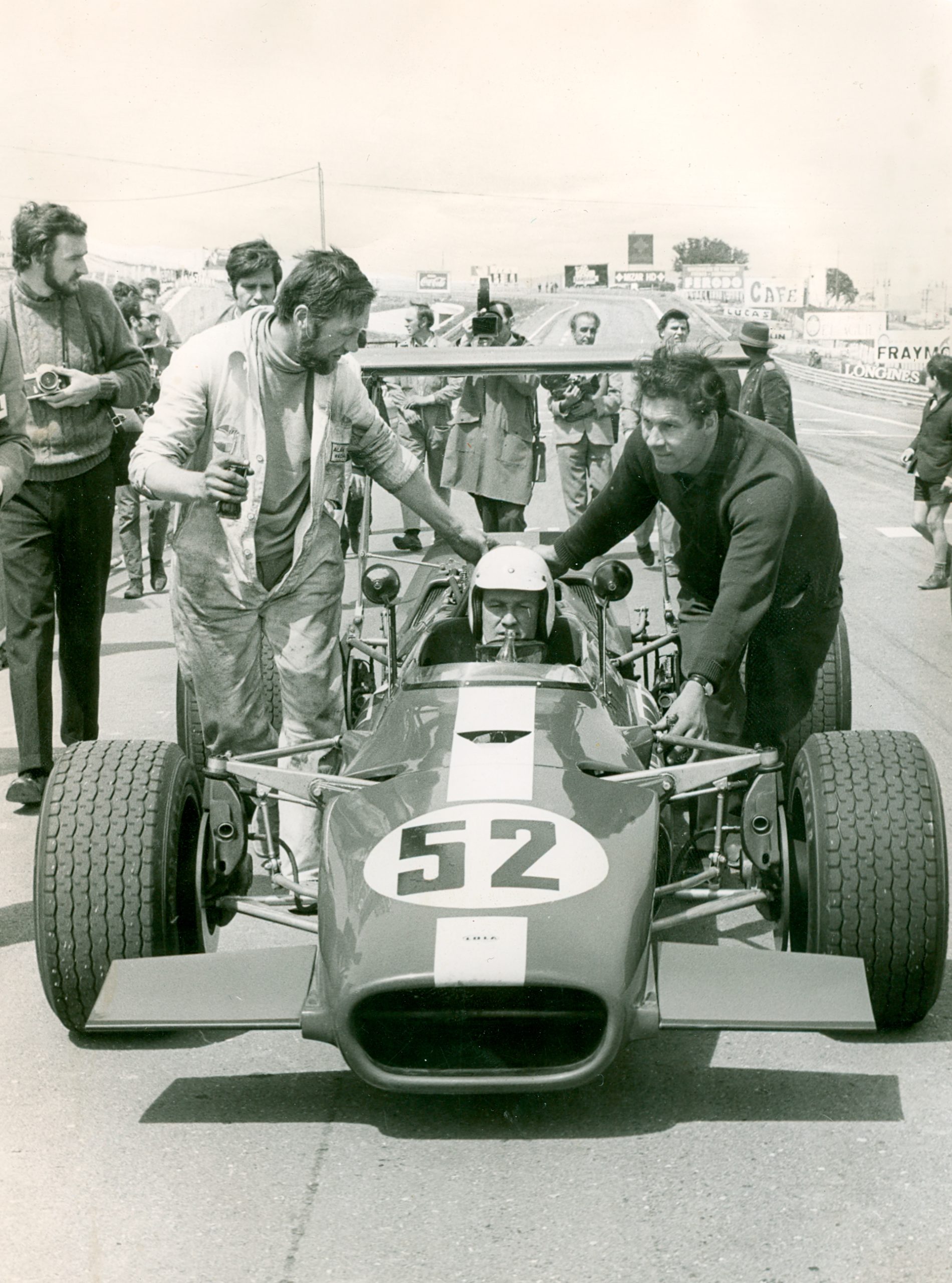

From a technological point of view, the two main highlights were the only 2 F1 cars to attend the race. The crème de la crème of them was probably Colin Crabbe´s Antique Automobiles Racing Team Cooper/Maserati T86, which was one of the best prepared cars on the grid, due to its competitive history and the team’s personal zeal.

The car that was now being used by the team was originally produced for the Cooper F1 Team in 1967, being retained as a reserve car throughout the 1968 season. After the bankruptcy of the Cooper Car Company at the end of the same year, the vehicle was purchased by Colin Crabbe, replacing the Brabham BT23C which, until then, was the team’s main machine. Therefore, the Antique Automobiles Racing Team would be the last squad to line up one of the legendary Cooper cars on the F1 grid.

If the history of this car wasn’t spectacular enough so far, another factor transformed the Cooper T86 into a special car in its own right. This specific machine was the only race car equipped with a Maserati Tipo 10 engine, a powertrain that still carried the legacy of the V12 engines that powered some of the all-conquering Maserati 250Fs at the end of the 1950s. Much lighter than the preceding generations of Maserati formula engines, it was considered at the time a masterpiece of engineering, as it was almost entirely made of high-quality aeronautical magnesium. However, all the effort put into developing this machine did not pay off on the track, as the engine proved to be extremely susceptible to breakdowns in high-stress situations (such as those present in 100% of the races).

The team’s #1 driver, Vic Elford, would not be available to participate in the race (due to his commitment to Porsche in the BOAC 500); so, it was up to Neil Corner to take on the role of team representative in Spain. The Briton had a discreet career in motorsports, standing out mainly in touring races between the 60s and 70s. The event in Jarama would be his first opportunity in an F1 cockpit.

The other F1 present was Tony Dean’s BRM P261. The car was one of the ex-Bernard White´s B.R.M.s, still equipped with a BRM P101 3.0 V12 engine. The vehicle spent practically the entire year of 1968 stored in the team’s garage, only being used in 3 non-championship races in England and the Italian GP, where the car did not qualify. Wanting to liquidate the team’s remaining assets after the delusional ’68 season, White managed to get rid of everything, including the now outdated P261.

The car found its new home in the personal team of Tony Dean, a driver who would achieve some success participating in several categories from the 60s onwards: Karts, Saloon Cars, WSC, Can-Am, F5000 and occasional participations in non-championship F1 races; all of these would be in the pilot’s curriculum by the end of his racing career, in late 80’s.

In addition to the 4 drivers mentioned, 4 others complemented the grid formation: Bill Stone would race with a Brabham belonging to Jack Smith. The car was an ex-Frank Williams BT18 F3, rebuilt as a BT18/21 to fit in the F2 parameters. What elevated the car’s category was mainly the replacement of the old Ford Holbay engine with an 1800cc Ford Twin Cam.

The remaining three cars were all F5000 representatives: Keith Holland, who was the main threat to Peter Gethin in the Guards Formula 5000 championship so far, entered the race in an Alan Fraser Racing Team Lola T142. This entry was another representative of the “American toughbreeds”, with a Chevrolet V8 prepared by Traco.

Jock Russell and Robs Lamplough came to Spain each with their own Lotus 43. Both were the same cars with which Team Lotus had experimented the unsuccessful BRM H16 engines in the 1966 and 67 Formula 1 seasons. After the project proved to be a resounding failure, Lotus just wanted to get rid of the vehicles, only being able to do so due to the high demand for single-seater chassis that the F5000 generated. To meet the category’s standards and also to be more competitive, the unreliable H16 engines were replaced by 4.7-liter Fords, the same ones used in the Shelby Cobra.

Due to the different weight-to-power ratio between the F1, F2 and F5000 cars, the solution was to add ballast to the more powerful cars, minimally equalizing the competition. Furthermore, it was stipulated that there would be 2 different classifications in the race: the first would only encompass the F1 and F2 cars, while the second would be reserved for the F5000 cars. But this did not in any way prevented the cars from racing together, as the Madrid GP had now been rebranded as a Formula Libre race.

A Sunny Day In Jarama

After two days of qualifying sessions, Peter Gethin and his McLaren were the ones who performed best, securing first place with a time of 1min31s9; it was almost 4 seconds faster than the second-best mark, set by Keith Holland. Sharing the second row were Tony Dean and Max Mosley, with Robs Lampough and Neil Corner in fifth and sixth positions, respectively. Closing the grid was the British Jock Russell, who was the slowest of all the drivers on the track, and Bill Stone, who, due to problems with his Brabham, skipped all sessions and would have to start in last position.

It was stipulated by the organization that the race would last 40 laps; in other words, much less than the 90 that had been contested in the 1968 Spanish GP, which took place in the same exact location. Even so, nothing that bothered the drivers, and even the public, who turned out in large numbers to watch the race on a sunny Sunday.

The eight cars finally lined up for the race in the early afternoon – and as soon as everyone was ready, the vehicles sped down the main straight of the Jarama circuit. The one who took the lead right at the start was Tony Dean who, taking advantage of all the torque of the BRM engine, overtook Gethin and Holland in a matter of meters.

But Dean’s joy was short-lived. At the Nuvolari curve, the driver misinterpreted the car gears, putting the vehicle in neutral. As a result, the BRM locked and the pilot lost control over the machine. Luckily, Dean managed to save his car in the final second, only suffering the scare of the spin. Part of Dean’s mistake can be credited to his inexperience with BRM, as this was also the driver’s first race in an F1 car.

Due to the chaos generated by Dean’s spin in the first corner, the field got mixed up. Leading at the end of the first lap was Keith Holland, with a quick Peter Gethin right behind. The one who was truly unlucky on the first lap was Robert Lamplough, who was forced to retire due to engine problems with his Lotus.

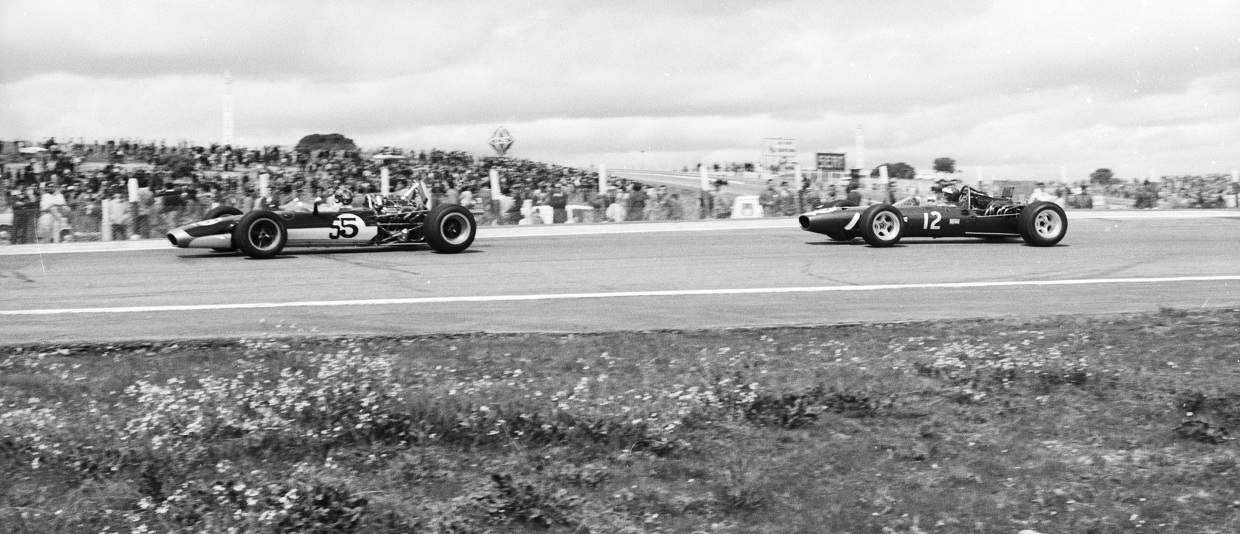

In the following laps, it didn’t take long for Holland and Gethin to begin to distance themselves from the rest of the field, demonstrating that the F5000s would have a clear advantage over the other competitors, even with added ballast. Further back, another interesting battle was developing, formed by Max Mosley, Neil Corner and the recovered Tony Dean.

Dean had no trouble overtaking Corner before the 10th lap, as the driver was struggling to maintain the pace with his Cooper, due to gearbox problems. But the soon to be duel between Mosley and Dean was fiercer. While Dean’s BRM took advantage of the straights of the circuit, where the F1 engine spoke loudest, Mosley made the most of the attributes of his Lotus F2, especially in the low-speed session between the Varzi and Portago curves.

Neither driver had a clear advantage in the confrontation until the 14th lap, when Mosley’s car began to lose speed. Having nothing to do with his opponent’s problems, Tony Dean snatched third place, leaving the crumbling Lotus behind. Mosley managed to get his car to the pits, only to discover that the injector nozzle broke away from the inlet manifold. The Lotus had been mortally wounded and there was nothing that could be done.

Meanwhile, the dispute for first place escalated in magnitude, with Holland and Gethin competing for every inch of ground, even going side by side in some corners of the circuit. Both alternated in the lead regularly, taking advantage of the straights where the 5-liter engines could unleash all their power. Therefore, every minute and a half, it was possible to watch the duo rumble the American V8s on the circuit’s finishing straight.

The race continued at this pace well after halfway through the race, with the battle for the lead being the biggest attraction of the show. With less than 10 laps to go, however, Keith Holland began to lose ground to Gethin, who had now opened up a few seconds in the lead. The Alan Fraser Team driver began to notice that the car was starting to overheat, and made the wise decision to let Gethin continue alone in the lead.

Holland’s caution at that moment ended up paying off in the final moments of the race. As Gethin opened the last lap of the race, the McLaren shook. Initially, it didn’t seem like anything serious, until the pilot started the climb in the central part of the Jarama circuit, when the engine simply died. With just over 2 kilometers to go before the final flag, the connecting-rod of the McLaren broke.

And Holland almost threw this golden opportunity away! The driver, still unaware of the Gethin incident, was giving everything he could, to try to get closer to McLaren in the final laps. Holland overdid in one of the corners and ended up taking a short ride in the run-off area close to where the now immobilized McLaren was. Luckily, Holland had already opened up a big lead over third-placed Dean, giving him enough time to recover from his mistake and head towards the finish line.

Keith Holland came first in the III Gran Premio de Madrid, completing the 40 laps in 1h03min29s8. Even though he did not complete the entire race, Peter Gethin had the second place on the podium as a consolation prize, as he was one lap ahead of third place Tony Dean in the final standings. Completing the top-5 of the race were Jock Russell, in fourth, and Neil Corner, in fifth place.

Epilogue

Even if the race was not a big failure as previously predicted in the final entry-list (the best point to prove it was the terrific battle between Holland and Gethin that lasted almost to the end), the III GP of Madrid had failed to prove its main point: that it was possible to host a major race without the support of federal and international bodies linked to motorsports.

The only exceptions to the case were perhaps the non-championship races that took place in the UK (such as the Race of Champions, the International Trophy and the Gold Cup), which continued to happen well into the 1970s. But the survival of these races was due to factors which did not exist during the Madrid GP: they were events that went beyond their nominal meaning; all were traditional races with a certain degree of international prestige; they were carried out in partnership with automobile clubs; and had the consent of the main F1 teams and drivers.

Therefore, it is not a question of saying that the Madrid GP was a failed experience. As a better definition, we can consider that this race only served as a confirmation that new winds were now blowing over the F1 circus. For the organizers, the learning process was quick: less than a month later, the IV Gran Premio de Madrid was held in Jarama, already announcing the return of the race to its original F2 format, which would continue until the last edition of the trophy, in 1971.

Acknowledgements

- British Magazine Autosport: edition of 18th April 1969 (pp. 14-15)

- British Magazine MotorSport: edition of May 1969 (p. 23)

- British Magazine Motoring News: edition of 17th Apr 1969 (p. 6)

- Website The Fastlane

- Forum GPL/DLR