Hans Stuck Biography

There he met the officer’s older sister who he would later marry. His family at the time was living in Switzerland due to the poor health of his mother, yet his father maintained numerous business interests in Germany. Stuck, after his marriage established a milk farm on an estate south of Munich and was soon doing milk deliveries into town. Stuck enjoyed the time spent making deliveries and soon made a game of it to see how fast he could make his deliveries. Like the legendary moonshine runners of the American south he would speed along the side roads of southern Germany. Whether the “milkshake” became a sore point with any of his clients is unknown! The seeds of his future hill-climbing exploits were being laid. He had earlier joined a local automobile club and his friends there urged him to enter a proper hillclimb being held near Baden-Baden. It was the summer of 1923 and Stuck was able to claim first in class. His appetite wetted, Stuck entered every hillclimb that would accept him. He soon made a name for himself but unfortunately his marriage would not hold up to this new life of racing.

Austro-Daimler took notice of this new driver and offered Stuck a deal that involved racing one of their sports cars in four upcoming hillclimbs. If he were successful they would give him a real car to continue his career. His first race ended half way up the hill when his car caught fire, the second, when he flipped the car and broke his leg and the third never got started when he over-revved his engine and blew it up. Yet the directors at Daimler saw something that led them to continue to support their erstwhile driver and so Tauern, in Austria would mark the make or break time for Stuck. Daimler’s faith in the young driver was rewarded when Stuck won the race beating the works drivers in their racecars. His reward was a position with the works team for 1927 and he promptly won nine major hillclimbs that year.

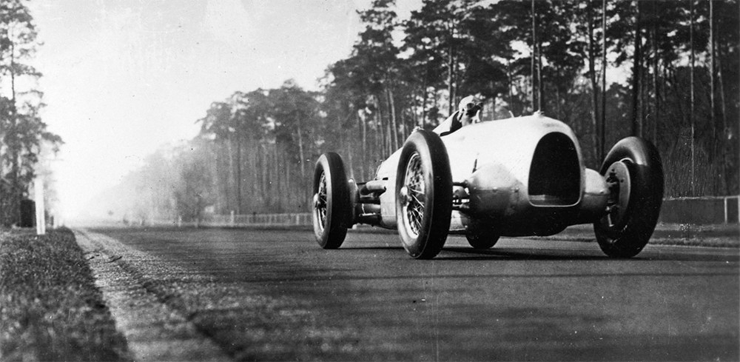

They were able to convince Hitler to divide the subsidy between two German teams. Stuck became the number one driver for the new team and on November of that year Stuck drove the new P-Wagen for its first trials. The Avus GP held on the 27th of May in 1934 would be its first race. Stuck built a huge lead on the field only to see his race end due to a broken clutch. After winning a couple of hillclimbs the most important race for the German teams had arrived, the German Grand Prix. After a race long duel with the Mercedes of Caracciola, Stuck crossed the finish line first and claimed what would become the greatest victory of his career. Later that year he won another important race, the Swiss Grand Prix by a whole lap. Stuck continued to master the hillclimb events earning for himself the sobriquet “King of the Mountains” though his record in Grand Prix racing was overshadowed by a new teammate in 1936, Bernd Rosemeyer.

For some strange reason Stuck never seamed to get the respect that he deserved from his team and at the end of 1937 he was fired from the Auto Union team. According to Stuck and denied by the team an important factor in his dismissal was that he had confided in Rosemeyer the confidentially of his contract with Auto Union. Seeing how much he was underpaid Rosemeyer demanded a new contract. Auto Union angered by this turn of events and claiming that Stuck’s best years were now long past, unceremoniously fired the driver who had so ably driven for them the last four years.

Not long afterwards his friends in the Nazi government interceded on his behalf. This coupled with the death of Rosemeyer and the weakness in their current driver line-up forced a reluctant Auto Union to re-sign their wayward driver in mid-season only a few months after his initial dismissal! Stuck had received help from the Nazi party in his career but there were others who suspected his wife of being part Jewish. To his credit he continued to defend his wife against these claims though it did not stop her from being discriminated against.

After the war he continued to drive and finally retired in 1960 after a remarkable career that spanned four decades. In 1978 he passed away and his son, Hans-Joachim continues to uphold the family name in racing.