1968: A Year Like No Other

1968 can be considered as the great year of the 60s: the uprisings in Czechoslovakia against the socialist rules, the increase in intensity and scale of the Vietnam War, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the first time that man orbited around the Moon. A troubled year for sure, but one that would cause great transformations for our society.

So what does Formula 1 have to do with it? Well, in 1968 the category also underwent one of its most profound reformulation processes, from the commercial, economic and technological aspects. We always remember that 1968 was the year in which wings and aerodynamic functions became the object of study and desire of all teams (and that at the end of the year, they already dominated the grid)

But, perhaps the most important of all the changes was the one promoted by Lotus at the beginning of the year: the insertion of master sponsorships, which caused shocks in the entire structure of motorsport. As common as this may seem today, where we see cars and teams filled with advertising and marketing, in the 60s this was almost a sin, a blatant attack on the entire institution of motorsport.

Even with the negative repercussions at the time, now we can see why Colin Chapman is considered one of the great visionaries of Formula 1, and responsible for much of what it is today. Thus, in these few lines, we are going to unfold the whys and reasons for Lotus to have changed the traditional green and yellow for red and gold, and its consequences in the team’s first victory in the new colors.

Part 1: Gold Leaf and Lotus

The end of the 1967 season did not look very auspicious for the Lotus team. Even with the successes achieved at the end of the year (the team had won the last two GPs of the season, in the United States and Mexico, in addition to the non-championship Spanish GP), Colin Chapman was concerned with the sustainability of the team, mainly due to the cohesion and professionalism, the hallmarks of the Team Lotus.

All of this depended on one simple factor: money. As the years went by, Formula 1 became a more professional, more technological and, consequently, more expensive sport. Teams no longer had the means to support themselves, and sponsors increasingly had to pay the bills. Thus, it became imperative to maintain good relations with them, so that they would want to finance the teams.

The decrease in profitability at the end of 1967 left the team’s finances on a tightrope: for the first race of the 1968 reason, in Africa, the team still had the resources to finance itself. “Desperate” might be too strong a word to describe Lotus’ situation after the 1968 South African Grand Prix, but it came pretty close to the word’s real meaning after it.

Therefore, for Team Lotus, the number 1 task for the break between the South African GP and the Tasman Series was to find a master sponsor that could bankroll the team; in addition, it was necessary to think of a new form of disclosure, which would influence greater capital than those obtained through traditional agreements.

The opportunity arose with the loosening promoted by the FIA regarding sponsorships, which occurred at the end of the 1967 season. Faced with the departure of historic sponsors (such as Esso and BP) from the category, the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile had to finally open itself to a new phase, in which motorsport advertising did not have to be exclusive related to car products; now, a new range of consumer goods began to appear in the race courses.

So, traditional brands like Shell, Goodyear and Dunlop would have to share their space with brands of cigarettes, drinks, home appliances and so many other things. And quickly for the teams, the choice for these sponsorships became an extremely attractive route: there were an infinity of agreements that influenced, with financial advantages that, until the first half of the sixties, were unthinkable.

The ground zero for sponsorship in F1 can be traced back to Team Gunston, at the 1968 South African Grand Prix, when John Love drove an orange and brown Brabham BT20, in the colors of the Gunston cigarette brand. Despite its pioneerism, Love’s entry was a one-off in the championship; Therefore, the Lotus Team can be credited as the first regular team to officially run an F1 championship in its sponsor’s colors.

Chapman was fast to foresee the sponsorship trend, when he signed an agreement with the Imperial Tobacco company in early 1968. As far as is known, the idea of sponsoring the English team with the cigarette brand came from two different initiatives, that converged in the end.

The “A” side of this story begins with Imperial Tobacco: at the end of the 1960s, cigarette manufacturing companies began to worry about the new European laws for advertising products that were harmful to health, mainly on television and radio. This directly affected Imperial Tobacco, which saw advertising through the media as its main means of promoting its products.

This, consequently, would entail a significant economic loss for the company, even more so after the relaunch of the Gold Leaf line of cigarettes, which needed an aggressive marketing campaign to be accepted by the market and to give revenue to the company.

The point is that Imperial Tobacco then began to look for new ways of promoting its products, trying to circumvent advertising restrictions; and it was in sports that it found the solution. Horse and boat races were the first attempts, which quickly bore fruit.

But it lacked that plus, the thing that would go beyond England’s national barriers to have a unique element of global propaganda. Furthermore, following the trend of other more traditional brands, Imperial Tobacco sought to renew itself, moving away from the image of a stale and stagnant product.

Here comes Lotus, as the “B” part that completes this story: since the end of the partnership with Esso at the end of 1967, the director of competitions for the Lotus F1 team, Andrew Ferguson, was looking for a new sponsor for the green and yellow cars from Hertfordshire. As a first step, Andrew prospected the market, trying to find out which companies would fit Lotus’s profile. Afterwards, it was the task to find out which sponsors would actually have the ‘means’ (a polite way of saying money) to display their brands on the Lotus cars.

After almost two hundred calls, letters and messages, the director of competitions did not get any concrete answers, only promises that could or not be fulfilled; in other words, there simply weren’t any interested parties!

At an echelon below Ferguson, however, events began to unfold in a way that would twist this story around. David Lazenby, head of Lotus Components (which together with Team Lotus and Lotus Cars Limited, formed the Lotus Group of Companies), was seeking sponsorship for two Lotus 47GTs, which would race for the team in some British touring car races in 1968. After Lazenby made the proposal public, Imperial Tobacco itself emerged as the main interested party, which now saw, in motorsport racing, the best place to seek its repositioning of the brand proposal.

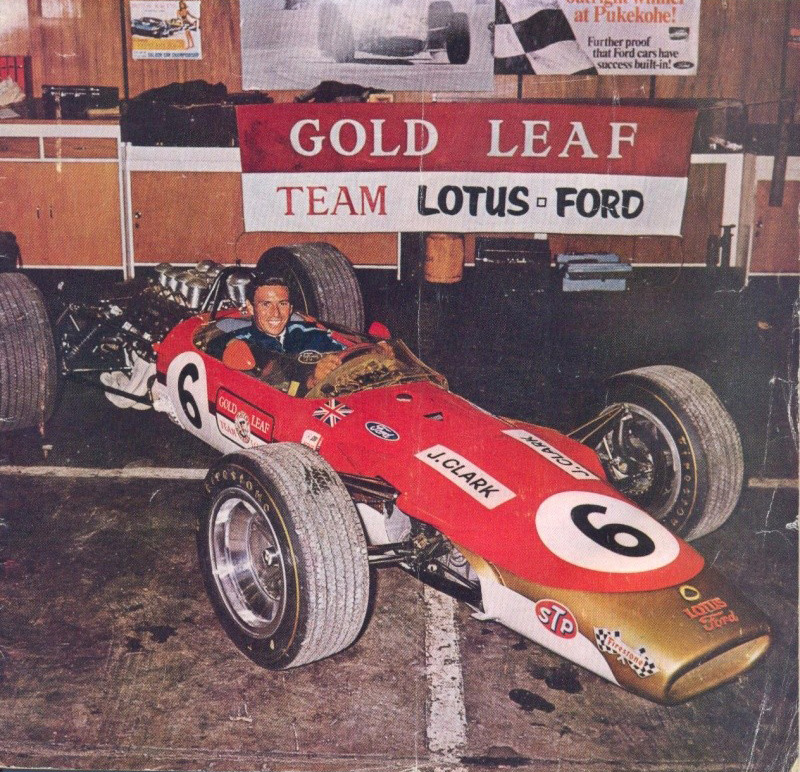

(PHOTO 4) Originally, the plan was for Gold Leaf to only sponsor the works team Lotus GT 47s, which would race in British national events. In the end, the sponsorship took on much greater proportions than those initially planned. Credits: Pinterest

The news of the pre-agreement did not take long to reach the ears of Andrew Ferguson, who quickly contacted Imperial Tobacco himself. Going directly to the source, the director of competitions tried to expand the original agreement, seeing if it could include not only touring cars, but also F1 and F2 single-seaters.

The cigarette brand was so impressed with the proposal that it was impossible to reject the deal. The agreement would be beneficial to both parties, on the sporting and the commercial side.

It was agreed that Imperial Tobacco would pay Lotus roughly £85,000 annually (*this figure was stipulated by a 2020 Bloomberg research on historical cigarette sponsorship in F1), provided the team agreed to a small set of conditions. The most controversial of these, without a doubt, was the clause for changing the colors of the cars. This went against what a large part of the grid valued at the time, which were the traditions, and which, for decades, dictated the pace of F1.

Until almost the end of the 60’s, most of the teams still strictly followed the etiquette, that the cars should be painted with the traditional motorsport colors linked to a country. For example, british racing green for England, white or silver for Germany, bleu de france for France, rosso corsa for Italy, and so on.

Even if still officially mandatory by the FIA, the national color rule was no longer strictly applied for a few years (mainly outside the F1 circle, where sponsorships already reigned in team colors). Even so, the great F1 teams were keen to continue following the tradition, which they believed to make a contribution, even if symbolic, to their home nations.

Only with this mindset can we understand what the Lotus team went through in that early 1968 year. From judgments of breaking the ‘gentleman’s code’ that governed F1, to accusations of selling its soul to a company that made such harmful products as cigarettes, even what one author put it as “in some eyes (Team Lotus) prostituted itself by swapping a national racing color – albeit with snazzy yellow stripe – in favor of the red, white and gold of its groundbreaking commercial partner.”

Pre-judgments could be made behind the curtains of the Formula 1 circle; but the real exchanges of offenses could only be done on the tracks and in the paddocks. And it is in the middle of the Tasman Series that it would be proved whether Colin Chapman had got it right again – or had made a fatal mistake.

Part 2: The Road to Wigram

The Tasman Series in the 1960s became almost a must-attend event for teams: in addition to being the best proving ground for equipment, it was used to test new technologies and drivers, in a reasonably competitive environment. Furthermore, the Down Under series of races did not have a high level of rigidity in the rules, being more open than the traditional FIA sanctioned events.

Another point that always took the teams to Australia and New Zealand was the profitability of the event, which, even with an almost minimal profit, was still positive. So why deny any money, even if it’s little?

The 1968 edition was undoubtedly one of the best, in terms of drivers and teams. Lotus and BRM took their official teams, while Brabham and Ferrari appeared with semi-works; almost another dozen smaller teams also participated in the dispute, which had eight legs in all.

In addition to the traditional lesser-known drivers from Australia and New Zealand, who competed only in races in Oceania and Southeast Asia, no less than 10 drivers who had been behind the wheel of a Formula 1 would be on the grid: Jim Clark, Graham Hill, Chris Amon, Piers Courage, Frank Gardner, Bruce McLaren, Pedro Rodrigues, Denny Hulme, Richard Attwood and Jack Brabham.

Even with such talent spread across the grid, the title dispute would be polarized in just two names: Jim Clark and Chris Amon. But the first two races of the season were disastrous for the still green and yellow Lotus: in the first leg, in Pukekohe, Clark (which would run as the sole works Lotus driver in the 4 stages in New Zealand, as Hill would only join the Lotus squad in the remaining leg in Australia) had to retire from the race while in the lead, due to engine problems. On the next stage, at Levin, the Lotus broke again, when Clark bent a radius rod through clipping the kerb in an attempt to overtake Amon.

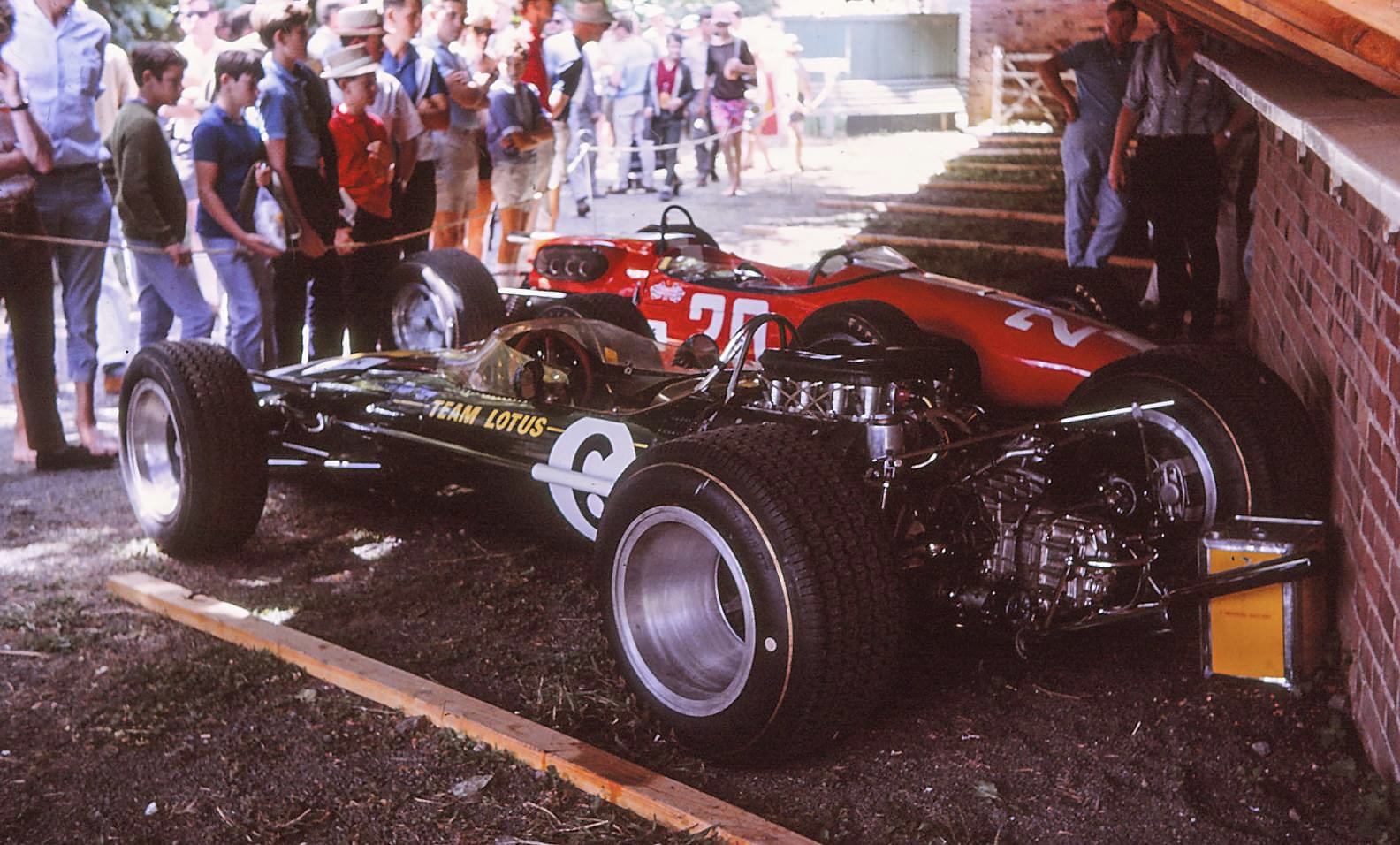

In both races, the winner was the New Zealander Chris Amon, who had opened 18 points of advantage for Lotus. Even though these two races ended in failures, both proved important for one reason: the first public appearances of the Lotus 49(T) in Gold Leaf’s red, white and gold livery.

In addition to the initial shock, another immediate repercussion was the rebuke to the team, which was banned from using the new paint scheme in both races. To get an idea, just look at what happened at Pukekohe: Clark’s newly painted Gold Leaf Lotus 49 had to be hastily repainted green and yellow, in order to pass the preliminary inspection and be cleared to enter the track.

These setbacks in no way affected Jim Clark and Colin Chapman, who saw in the third leg of the series, in Wigram, the chance to remount.

Part 3: The Christchurch Duel

The Lady Wigram Trophy traces its origins back to 1951 when Les Moore made his name in history by marking the race’s first winner. Until 1968, there had been 10 winners in 16 editions (the race was not held in 1955); being the record holder for most wins so far Peter Whitehead, with 3.

For the 1968 edition, 19 cars were entered. In addition to the aforementioned F1 cars adapted to Tasman Series specifications, such as Ferrari, Lotus, Brabham and BRM, there were a dozen updated F2 and Formula Libre vehicles that would compete in the race.

Most of these cars (usually Brabhams, but also containing Lotuses and McLarens) were equipped with older engines such as the Ford Twin Cam and the Climax FPF; consequently, they were no match for the adapted 1.6/2.4/2.5l Tasman engines that were used by the big players.

Even if most of the circuits were not high-speed, which somewhat nullified the power advantage, at the end of the day, it was always the Tasman Formula one´s that found themselves in front. The machine made as much difference as the driver behind the wheel.

For this stage, Lotus still had only one pilot: Jim Clark. Even with the problems in the last few races, it was still considered that he and his car formed the most harmonious duo on the grid. This was due to the fact that, before both retirements in the previous stages, Clark was with a better pace than his competitors.

The Lotus Model 49 had its problems, which was a hereditary thing in the designs of the Lotus team cars: the creation of cars made them extremely competitive machines, but they were very untimely when they wanted to be.

On the other hand, Chris Amon’s Ferrari has performed in an exemplary way so far. The 2.4-litre Dino engine proved to be extremely reliable, making Amon comfortably come first in both races.

One of the factors that led the Kiwi driver to these two excellent results was his patience and tenacity, in waiting for his opponents’ mistakes. Another point is that Amon knew he would have to do good results in the New Zealand leg of the races, knowing that Lotus would soon start its ascent (with the presumable resolution of the problems and the arrival of Hill in the Australian stages), and Ferrari, the descending (as it was known that the Dino engine could not beat the Cosworth in an attrition battle).

There were fears that the weather would not be friendly for the pilots during the entire stint of the Lady Wigram Trophy, with constant rain in the week preceding the race. Therefore, the first track recognition training sessions were held only on the day before the race. Nothing that made much difference, as for most drivers this was not the first time on the Wigram circuit.

Demonstrating that the problems of the last stages would not affect his performance, Clark was the one who set the best times on the track: for example, in the morning session, with the floor still wet, the Lotus scored almost an average of 100 mph on the timed lap. In the afternoon practices, with the asphalt almost dry, Jim Clark surpassed the ‘100 limit’, reaching 103.5 mph and clocking 1min 20.0 sec.

The second fastest time could only have been set by none other than Chris Amon. Despite difficulties faced at the beginning of the practice session, mainly due to engine problems (these were perhaps the first signs of decline of the Dino in the 1968 TS), the New Zealander managed to set a time of 1 min 20.6 sec.

And it was for just a marginal gap that Amon did not lose the second position, since Denny Hulme, in a Brabham BT23 updated for the Tasman Spec, was only two tenths of a second behind the pilot and his Ferrari.

Of the lesser carat pilots, Frank Gardner, on a Brabham-Alfa BT23D, came out the best. The Australian’s time was almost a second slower than Clark’s; but even so, it was still a spectacular result, since the car was much less technologically refined than other cars on the grid.

Much was also due to the talent of Gardner, who had raced in Formula 1 between 1964 and 1965 for John Willment Automobiles. In this display of skill, the pilot demonstrated that the disdained machines also deserved a little attention.

Jim Clark’s resounding result in these trainings also served to highlight another twist: the Lotus Team was now finally allowed to change its colors. The striking green and yellow that had accompanied the team until now finally gave way to gold and red.

Perhaps those who believe in superstition could say that this change coincided with Lotus’s turning point in the Tasman Series. The most realistic ones can say that this is nothing more than a simple coincidence. Be that as it may be, that January 19, 1968, marked the first of the Lotus team’s “Cigarette Days”.

The only certainty we can have is that it wasn’t Imperial Tobacco that directly influenced Jim Clark’s performance, as it was known that the pilot was a non-smoker; something quite contrasting with the general environment of Formula 1 at the time.

Leaving the conjectures to the side of the road, we return to the facts: Clark’s best time in training did not guarantee the Scotsman the first position in the general race, but only the right to start in the first position in the first pre-qualifying round. This was due to the format chosen by the organizers for the dispute of the trophy.

First, two heats of 11 laps each would be held: the first heat would be exclusive to cars with 1.5-liter engines (the Twin Cams and Climaxes FPF), while the second would be composed of cars with engines from 1.6 to 2.5 liters (Cosworths, Dinos, BRM Ps and Alfas). After these sprint heats, the race that would be worth the trophy would be held, with 44 laps.

To the relief of the organizers, January 20, 1968, dawned with clear weather, despite constant gusts of wind that swept the circuit; nothing that bothered the audience present, which anticipated the duel between Clark and Amon.

Right in the first heat, it was demonstrated that that Sunday would be a promising day for motorsport lovers. The race between the 1.5-liter cars was very close, mainly due to the exciting dispute for first place, between Roly Levis and Bill Stone. Levis, in a Brabham BT18 Twin Cam, managed to cross the finish line with only 0.1s of advantage over Stone, after an overtaking achieved on the 5th lap.

In the battery for cars between 1.6 and 2.5 liters, right on the first lap, a surprise cheered the audience: Gardner was able to have a better start, managing to take the first position.

It’s okay that the Australian’s joy would be short-lived, as at turn eight (known as The Harpin), the Alfa gave way to Ferrari in the number one position of the race. On the next lap, Clark wasted no time and simply imitated Amon’s maneuver, now relegating Gardner’s Brabham-Alfa to third position.

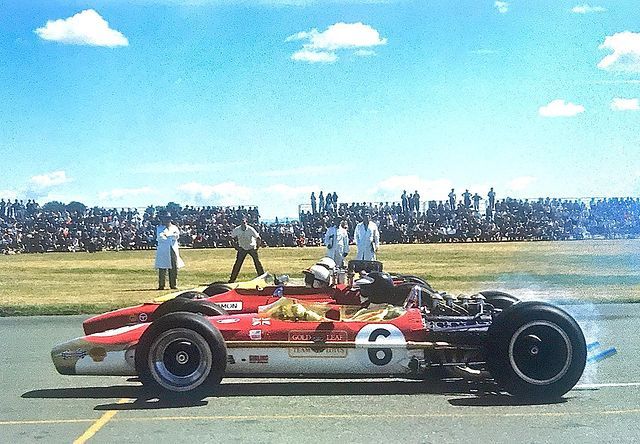

The first duel between Jim Clark and Chris Amon quickly developed. And just as quickly, it was resolved, when Clark, at the end of the third lap, passed Amon. But the Kiwi was not going to let Lotus, in its first race in the new colors, win that easily.

Thus, the confrontation between both lasted until the checkered flag, when Clark crossed with 1.0s of advantage over the Ferrari. Even with the New Zealander’s clear boldness, the Scotsman had not given any clear chance of recovery for Ferrari. A well-deserved win for Lotus, without a doubt.

The dominance of the two drivers was so clear that Gardner, who had to settle for 3rd place, arrived 17s behind Clark (this on a circuit where lap times were close to 1min20s!). Denis Hulme and Piers Courage completed the top 5.

Now came the moment of truth. Of the 19 officially entered cars, 18 lined up on the grid for the decisive race of the Lady Wigram Trophy (the only exception was the New Zealander Peter Yock, who on the second lap of the heat for cars up-1.6 liters, spun into one of the markers drums, deranging the Lotus’s suspension and putting an end to his weekend in Wigram).

The grid was set up in a 3 x 2 x 3 x 2 x 3 x 2 x 3 scheme: Jim Clark, Chris Amon and Frank Gardner would again open the grid. In the second row came Hulme and Courage; right behind, the Mexican Pedro Rodriguez, the New Zealander Bruce Mclaren and the Australian Paul Bolton, the latter being the first representative of the 1.5 liters on the grid; next in order, we have Jim Palmer and “Red” Dawson; Graeme Lawrence, Levis and Stone; Ken Smith and David Oxton; ending with Graham McRae, Don Macdonald and Bryan Faloon.

This time, there were no surprises, as Clark and Amon took the top two positions at Hanger Bend. Gardner, on the other hand, had a tricky start, dropping from third to sixth before the first corner.

The Lotus and the Ferrari seemed to first aim to liquidate the competition together, and then solve their problems with each other. Because of that, after four laps, both cars had already managed to open almost 7 and a half seconds in relation to Hulme, who was in third.

The Brabham driver, apparently, had already given up the dispute for the first place, aiming as a more immediate objective to secure his spot on the podium, since this was under threat. This was due to the menacing tone of Piers Courage’s McLaren M4A, which appeared closer and closer to his rear view mirror.

As this battle raged on, Clark and Amon faced their first big challenge when they started to put laps on the stragglers as early as the sixth lap. Incredible as it may seem, the two wasted no time on this task; on the contrary, when they finished passing through the pack of 1.5 liter cars, they had widened the gap to 10s over Hulme.

Who could not resist this relentless pace was James Gardner; after a bad start, he had to retire from the race on the 7th lap, when the head gasket on his Alfa V8 engine failed. Total bad luck for the Australian, after brilliant performances in practice and in the pre-qualifying heat.

After that, the race degenerated into an arrangement of small skirmishes: Clark and Amon in front; followed at a distance by Hulme and Courage; having a little more behind Rodriguez and McLaren.

Of these small battles, the one that lasted the least was between teammates Pedro Rodriguez and Bruce McLaren. On the 19th lap, the Mexican had a sticking throttle-slide problem, being forced to visit the pits to fix the problem. The stop wasn’t very long, but it was enough for McLaren to open up a comfortable advantage for Rodriguez and his BRM P261.

Hulme had also managed to fend off the threat of Courage over the course of the laps. The New Zealander followed at a steady pace, which completely annulled all overtaking attempts made by his pursuer. This frustration practically placated the English driver, who had to settle for fourth place.

But those who dealt the cards were certainly Clark and Amon. Near the halfway race, the two had managed to build up a 40s lead over Hulme. With that huge margin of time, then, the true duel between the two pilots began.

Amon tried to position himself for a decisive attack, but Clark didn’t want to know about Kiwi’s plans. Between laps 20 and 30, the flying Scotsman did what he did best: he mentally destroyed his immediate opponents, with an overwhelming pace.

In another of his masterful performances, Clark opened up almost 7s of difference to the Ferrari. Under normal conditions, this would already be considered a spectacular feat; but if we take into account the short lap length of the circuit (only 3,540 km long), the many stragglers that plagued the path and the numerous reliability problems that the Lotus 49 had, this appearance becomes even more special.

This almost put an end to the dispute for the first place, as, in the final laps, Amon did not even bother to try to recover the ground lost to the Lotus.

After 44 laps, Jim Clark crossed the finish line in first place, with an average speed of 102.6mph (6.61mph faster than the record set the previous year by Jackie Stewart). Chris Amon was right behind, with almost 8s of disadvantage for the Scotsman.

Even though Clark’s performance overshadowed all of the other contestants, it’s worth noting the work done not only by him, but by Amon himself. Both drivers overtook every car on the track at least 1 time. No wonder the closest riders (Hulme third; Courage fourth; Mclaren fifth; Rodriguez sixth) were all a lap down in the final standings – they were simply in a race of their own at Wigram.

In addition to winning the Lady Wigram Trophy and with it, the first points in the 1968 Tasman Series championship table, Clark tied Whitehead’s record with three trophy win. Besides that, the Scot took home the prize of US$1000 (currently around US$8700). It may not seem like much, but for the 60s Formula 1 driver, believe me, it was a hefty sum!

Part 4: Epilogue

Clark’s win at Wigram was the first of four that the now official Gold Leaf Team Lotus would take home in the 1968 Tasman Series. Most notably in Australia, where a three-winning streak (at Surfers Paradise, Warwick Farm and Sandown) would take the Scot to the top of the standings and the ultimate championship title.

A major contributor to this was also the descendant of Ferrari and the Dino engine, which Chris Amon so feared: after Amon’s second place at Wigram, the only other good result achieved all season was another second at Sandown. For the rest, two fourth places at Teretonga and Warwick Farm, a seventh at Longford and a retirement at Surfers Paradise; results that weren’t enough to hold Clark’s charge in the Australian leg of the race.

But the big reasons behind the real importance of the 1968 Tasman Series boil down to two things: the first is impossible not to mention, that they were Clark’s last major appearances in a racing car, as the driver would pass away in the II Deutschland Trophäe (F2), at the Hockenheimring, just one month after the last race of the Series.

Here is not the space to make conjectures about the causes and aftermaths of the accident, but it can be said that the pilot’s death was a great shock for everyone in the circle of Formula 1; especially for Colin Chapman, who, in addition to owning the Team Lotus, was a mentor and close friend to the Scotsman.

But Formula 1 could not stop, and so we reached the second point of importance for the 1968 Tasman and the regular F1 season as a whole: Clark had given the first glories to Gold Leaf Team Lotus; it was now up to another driver to keep the momentum going.

Between 1968 and 1971, when the red, white and gold reigned in British cars, the team won two drivers’ and constructors’ titles (in 1968 with Graham Hill, and in 1970 with Jochen Rindt), which gave a significant boost to this symbiotic relationship between Imperial Tobacco and Lotus itself.

The agreement lasted until 1986, first with Gold Leaf, and then, with the even more memorable black and gold colors of John Player, and was undoubtedly one of the most prolific and lasting partnerships in Formula 1. Looking back now, we can say that with that fearless move, Colin Chapman’s genius encompassed not only the automotive aspect of cars, seeing that the category was much more than an embryonic place of technology.

Andrew Ferguson and David Lazenby extrapolated this meaning, giving Formula 1 the first contours of what it would be today: not only a space of speed, but also of advertising. Until the 1960s, Formula 1 was a big blank canvas, and as soon as its potential was observed and considered, a new world emerged.

Acknowledgments

- The Jim Clark Trust

- OldRacingCars Website

- Bruce Sergent Website

- MotorSport Magazine

- Money Sport Media Limited 2020 (article): Driving Addiction – F1 and Tobacco Advertising

Disclaimer: This text does not intend to glorify any brand of cigarettes and are only mentioned for historical purposes and contextualization of certain moments and events.