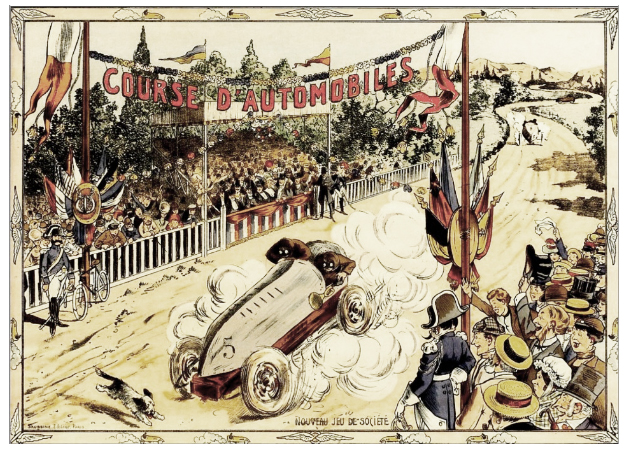

The great city-to-city races were the origin of motor-racing. Attempts had been made to organize an event back in 1887, but the the Paris-Rouen reliability test of 1894 saw motor-cars take to the roads to compete for the first time. The following decade saw interest in the events increase dramatically, and more competitors meant more events. The speeds increased too; with Henri Fournier’s average speed in the 1901 Paris-Berlin race being quadruple that of Count de Dion in 1894.

Increased speeds and increased numbers of spectators (often poorly marshaled spectators, not aware of the dangers the cars posed) perhaps inevitably led to rising casualties among competitors and spectators alike. This reached boiling point at the 1903 Paris-Madrid event, the “Race to Death”, which was curtailed at Bordeaux as shaken-competitors refused to race any further. The French authorities, who had always been to the fore when organizing road-races, promptly ceased to sanction this type of event. While road-races continued they were now primarily to be found on closed-circuits, albeit very long circuits, and the first great era of motor-racing had come to a close.

No Subscription? You’re missing out

Get immediate ad-free access to all our premium content.

Get Started