In the long staircase of world motorsport, it is common for us to focus mainly on the greatest successes of drivers in the main categories. If a driver manages to arrive and establish himself in Formula 1, his greatest legacy will certainly be due to his performance in this category. The same case happens in endurance, when success in IMSA and WEC are those watersheds in any driver’s career.

Perhaps it will be forgotten, however, that most pilots have a journey behind them, followed by different paths that took them to the pinnacle of their careers. Today, due to the expansion of the media, which provides motorsport lovers with the possibility of seeing the most diverse modalities and categories of the sport, this can be mitigated to a certain extent – for example, through live streams in television or internet, one can not only watch the F1, but F2, F3, the Macau and Pau GPs; information that 40 years ago depended on a monthly magazine report for you to find out about.

So, it is no surprise that the successes of the drivers of the 50s and 60s in the sub-F1 categories have fallen into ostracism. Perhaps with the exception of Jochen Rindt’s period of dominance in F2 in the late 60s and the successes of Pescarolo and Beltoise for Matra in its pre-F1 years (which were widely covered by the French media), little is said in depth about the victories and achievements of these drivers in F2, F3 and FJ during these decades.

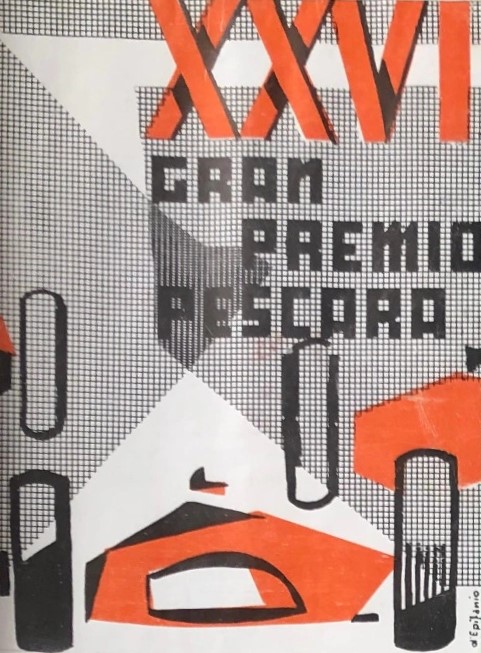

One of the most spectacular and little-known cases was the victory of a still unknown Denny Hulme in the XXVI Gran Premio di Pescara, valid for the 1960 Formula Junior championship. The young driver had to face one of the most qualified grids in the ephemeral history of FJ, being challenged by many other drivers who, in the following years, would also become his opponents in F1.

PESCARA: THE PEARL OF THE ADRIATIC

Before talking about this race in 1960, it is worth going back to the mid-1920s, as it was around this time that the Pescara circuit had its origins. Born from the Italians’ incessant passion for speed (and tempered with other political factors), the first event on the circuit took place in 1924, with races happening on the circuit almost uninterruptedly until the beginning of the Second World War (the exception being 1929, because of works in the Pescara-Penne railway that blocked part of the circuit, which became for a year a construction site).

After the hiatus caused by the global conflict, activities soon returned to the circuit, mainly due to the prestige acquired by the venue in the pre-war years, and also because of the popularity of the Coppa Acerbo and the Targa Abruzzi not only with the public, but with the pilots themselves.

In its ‘second incarnation’, the event went through a process of modifications, mainly regarding the identity of the race. Firstly, the Coppa Acerbo nomenclature would be abolished from the trophy, as the organizers sought to leave behind the race’s fascist origins, adapting it to the new motorsport that was emerging from the ashes of Europe. This in no way meant forgetting the triumphs of past winners; therefore, as a way of maintaining this legacy, the race numbering would continue from the last GP contested before the war (the XV Coppa Acerbo/Pescara GP). Another important point was the abolition of the Targa Abruzzi, as the organization now sought to focus on organizing just one large scale event.

Regarding the circuit itself, however, almost no modifications had been made to the track – and it would be that way practically throughout this second stint of the GP. With the exception of the occasional resurfacing of some parts of the track over the years, in addition to guardrails and protections in certain more dangerous parts, the 1960 track was practically the same as that of 1924.

Because of this, the Pescara circuit went down in history as one of the most challenging circuits used in high-performance motorsport, surpassing to a certain extent even the legendaries Nurbürgring and Spa-Francochamps. The mystique (which at the same time could be considered the track’s infamy) lay in the fact that Pescara was a high-speed street circuit, as almost 2/3 of the 25 km-long lap were covered by straights. On the other hand, the other 1/3 was made up of tight curves, mainly in the section that went from the city of Pescara to the small village of Villa St. Maria.

Even with danger lurking at every turn, Pescara continued to be an almost sacred place for pilots. Not surprisingly, in 1957 the location was chosen at the last minute to host the Italian F1 Grand Prix, something that would be, at the same time, the track’s highmark, but also the start of the period of decline of the track. After the 1957 GP, it was assessed that, even according to the suggestive safety standards of the time, any race that took place in Pescara was a Russian Roulette – in other words, a disaster waiting to happen.

But that didn’t stop the organizers from trying to organize the Pescara GP once again. After the cancellation of the 1958 and 1959 editions, we arrive again in 1960: far from its glory days, Pescara still stood the test of time, as one of the few survivors of the golden age of motorsport in the 1920s. And there’s nothing like a cool summer day to bring the magic of the past back to a legendary circuit.

THE 1960 FORMULA JUNIOR SCENARIO

The XXVI Gran Premio di Pescara of 1960 would be part of the Campionato A.N.P.E.C. / Auto Italiana d’Europa, which was just 1 of the 3 FJ championships that took place simultaneously in Italy. After the birth of the Formula Junior in 1958 and its consolidation in 1959, 1960 proved to be the year in which the category really established itself among the great brands of world motorsport.

As a practical example, it is enough to note that in 1960 there were already 3 FJ championships in England, 2 in the United States, in addition to national championships in France, Austria, Germany (West and East), not to mention numerous one-off races in another dozen countries, such as Sweden, Finland, Yugoslavia and even Cuba.

Therefore, it is not surprising that in the birthplace of FJ, there was also a vast profusion of championships available to competitors: the first alternative was the so-called ‘Prove Addestrativi’ championship, which consisted of 11 races held on Monza and Vallelunga circuits. This championship was exclusive to Italian drivers, many of whom were having their first contact with high-performance motorsport.

The second option was the ‘Campionato Italiano’ itself, for more experienced drivers. In 1960, this championship consisted of 10 events, spread across different circuits in the tarantella land. Again, only Italian drivers could score points in the classification of this championship. The thing is that some stages of the ‘Campionato Italiano’ were also part of what was called ‘Campionato A.N.P.E.C. / Auto Italiana d’Europa’, the third and most prestigious option.

Despite being considered a national championship, the Campionato A.N.P.E.C. / Auto Italiana d’Europa was almost an international challenge in its conception. In addition to being open to all drivers, regardless of nationality or car origin, the championship was made up of races not only inside Italy, but also outside of it.

For 1960, it was stipulated that the Campionato A.N.P.E.C. would have 12 stages, spread across 5 countries. In the end, only 10 of these races were contested (as 2 scheduled events in Germany, the Einfelrennen and the Solituderennen, were canceled during the championship). It involved drivers from Europe, North and South Americas, Oceania and Africa.

Due to its history and its importance in world motorsport, it was decided that Pescara would have to be part of this ever-growing international circle of Formula Junior races. After a 2-year hiatus from the track on the international scene, the Pescara GP would officially become the 7th stage of the Campionato A.N.P.E.C. / Auto Italiana d’Europa of 1960.

THE MAIN STARS AND CONTENDERS

The race in Pescara would be marked by two factors from the human material aspect: at the same time that there was a huge number of drivers registered for the race (56), the quality aspect also stood out, with several excellent names appearing to compete for the trophy in the city of Abruzzi.

The first name to be mentioned must be that of the hitherto leader of the Campionato A.N.P.E.C. / Auto Italiana d’Europa from 1960, the British driver Colin Davis. After his victories in the II Gran Premio della Lotteria di Monza and the II Gran Premio di Messina, the driver was in the isolated lead of the championship, with 45 points.

Born in England, the driver had spent a huge part of his professional career in Italian motorsport – that’s why most of his accomplishments were in the Italian lands, like the victories in the 1957 Coppa d’Oro di Sicilia and the 1959 Messina GP. But his greatest achievements to date were his victory in the +2.0 GT class in the 1000 km Nürburgring of 1960 (alongside the Italian Carlo Abate), in addition to his participation in F1 for Scuderia Centro-Sud, during the 1959 season.

Who would be the immediate pursuer of Davis at the Pescara GP would be an unknown Denny Hulme, who, in 1960, was having his first racing experience outside southwest Asia. Even though he was still far from the fame that would embrace the driver in the following years, Hulme had already shown his credentials during the season, achieving a great third place in the II Gran Premio della Lotteria di Monza.

But certainly, those with most eyes on that edition of the Pescara GP would be the members of the trio of the most promising Italian drivers of the ‘Formula Junior Generation’: Giancarlo Baghetti, Ludovico Scarfiotti and Lorenzo Bandini.

Baghetti and Bandini were already veterans of Formula Junior, with both having already collected some successes during the Italian seasons of the category (for example, Baghetti had already won a stage of the 1960 Campionato A.N.P.E.C., the VIII Trofeo Bruno and Fofi Vigorelli, held in Monza).

In contrast, Scarfiotti, who despite having been racing for Scuderia Ferrari in the WSC since the end of 1959, was still trying to crave his marks in single-seaters. But as it would prove, Pescara would be a turning point in the discipline for the young Italian driver.

Another one who deserves a mention is the Rhodesian John Love. At a time when it was not common for Africans to compete in races in Europe, Love was one of the pioneers in bringing the identity of the southern axis to the circuits of the northern hemisphere.

The driver’s name would become known mainly due to his constant appearances in the South African GPs in the 60s, becoming a Rhodesian hero after his second place in the 1967 edition of the GP. But in 1960, Love was still one of hundreds of those who had ambitions to become a world-class driver.

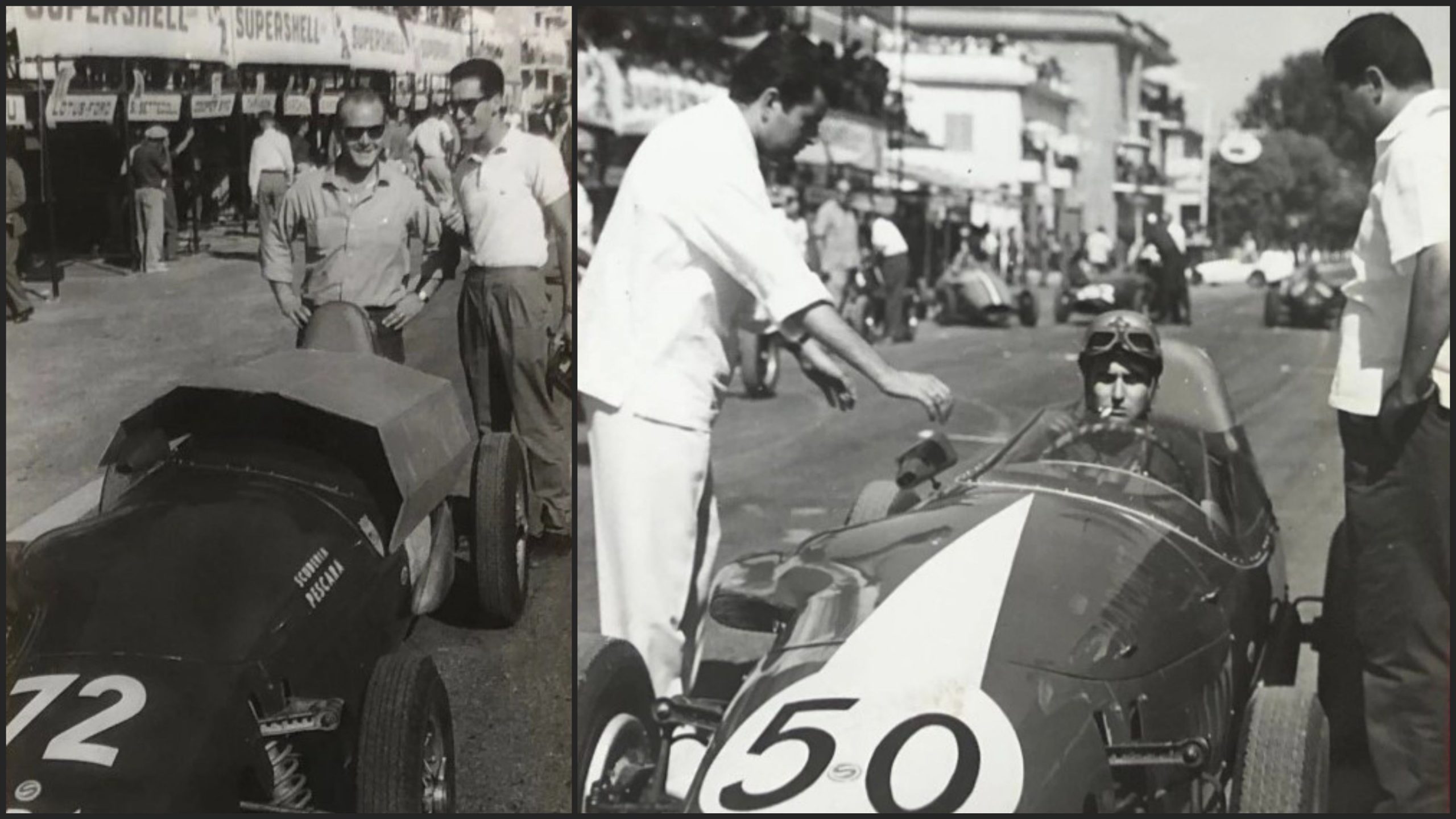

One thing that Love couldn’t complain about would certainly be the team he had behind him. Tyrrell Racing, in its second year of operations, was already one of the most serious and committed teams in the Formula Junior racing scene. This was an identity that had been forged in the early days of the team’s existence in 1959, when “Ken” Tyrrell closed the deal that would give a great return in the following years: the partnership with the Cooper Car Company, with Tyrrell basically being the official works team of the British automaker in the FJ.

Some other interesting names also appeared at that race in Pescara: for example, the Dutchman Rob Slotemaker and the Frenchman Henri Grandsire, both of whom would become recurring figures in the endurance races of the 60s.

Representing some F1 veterans were the Italian-Argentine designer Alejandro de Tomaso, who between 1957 and 1959, enjoyed a brief stint in the circles of the most prestigious category in world motorsport. Piero Drogo, who had participated in the 1959 Italian GP and some other non-championship races in the category in the same year, also welcomed the challenge in Pescara

Another pilot who could also stand out in the race was the leader of the ‘Campionato Italiano’’ of Formula Juniors, Renato Pirocchi. After the good results achieved by the pilot in Teramo, Caserta, Monza and Salerno, it seemed that the driver could be one of the main inconveniences for the main trophy contenders.

THE XXVI GRAN PREMIO DI PESCARA

The GP was scheduled to take place on August 15th, comprising a series of races for Formula Junior cars. Due to the number of participants who would take part in the competition, it was decided that 2 semi-final rounds would be held before the big final. In total, of the 56 cars originally registered on the entry-list, 54 arrived on the pescarese lands before the official activities on the circuit began.

And as soon as the results of the qualifying sessions were defined, the drivers were separated into two groups, each containing 27 cars. In this first phase, the drivers would compete in a sprint race, lasting 3 laps. As the main criterion for classification for the final race, which would be held in another 7-lap race, there was a minimum speed coefficient, a calculation that would encompass the times achieved not only in the race itself, but also in qualifying sessions.

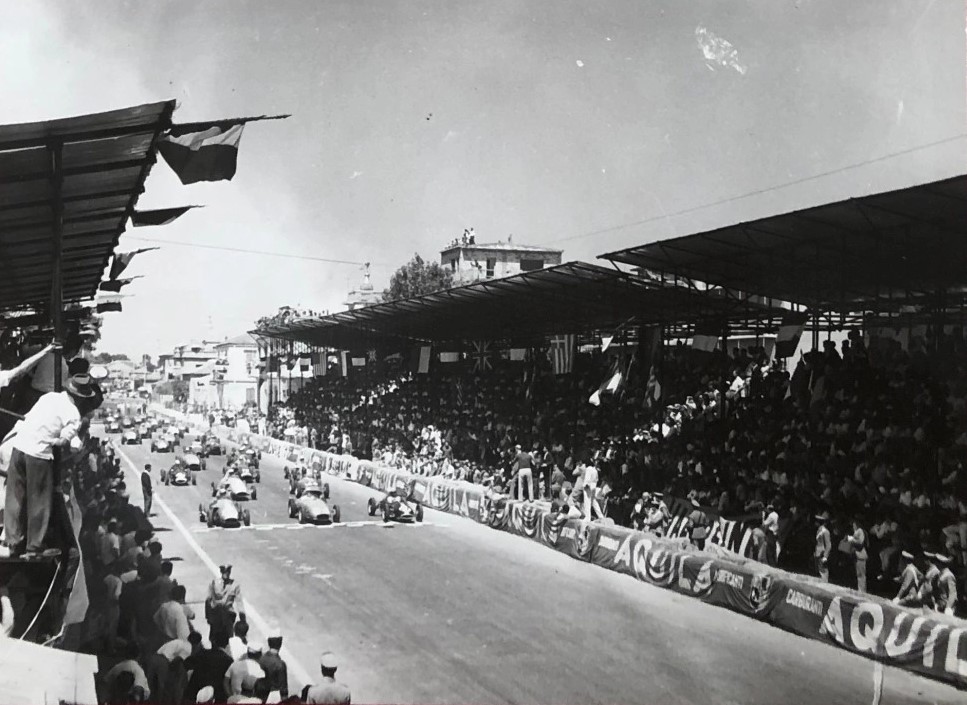

A pleasant Sunday was emerging over Pescara, with just a light breeze from the Adriatic blowing through the thousands of spectators who had been so familiar with the streets that were now part of the circuit. After a celebration, which included representatives from the national and municipal government, the competition for the XXVI Gran Premio di Pescara was officially declared open.

In the previous day’s qualifying sessions, the Italian Renato Pirocchi secured first place in the first heat, with an extraordinary timed lap of 11min11s in a Stanguellini-FIAT. According to media comments at the time, Pirocchi’s time was so spectacular that it was seriously considered the hypothesis that the timekeeper made a mistake in clocking the driver’s qualifying lap (whether intentionally or not). But as no evidence was found to support such suspicion, the case never went beyond the speculation stage.

Even so, there was certain evidence that gave some basis to the theory: for example, in second place, with a time of 11min24s9 (that is, 13 seconds slower than Pirocchi!) was Colin Davis, in an OSCA-FIAT. Completing the front row and with a time 5 seconds slower than Davis, was Rhodesian John Love, who achieved a good mark of 11min29s1.

The checkered flag was scheduled to take place at 8:50 am, and when the moment arrived, the 27 cars raced down the main straight of the circuit in the coast of the Adriatic. The best starter was John Love, who took first place in the first few meters of the race.

But the African’s joy only lasted a few kilometers, as in the middle of the zig-zag sequence on the outskirts of Spoltore, Colin Davis managed to pull over a beautiful maneuver, overtaking the Cooper in the place where the British car performed best: in the curves and twisty parts of the circuit.

At the end of the first lap, it was Davis and his OSCA who were leading, 5 seconds ahead of another OSCA, this one driven by Ludovico Scarfiotti. The Italian had managed to close in on Love in the section between Capelle and Monte Silvano, executing the attack at the end of the long straight section. Love couldn’t do anything, as his Cooper didn’t have the power to challenge the FIAT powered OSCA on the straights.

Just behind the fight for the podium, was the Argentine Juan Manuel Bordeu, who had now relegated Pirocchi to 5th position. Bordeu, at the time, was seen as one of the greatest promises of Argentine motorsport after the country’s victorious generation of the 1950s. Not surprisingly, J.M. Bordeau was one of Fangio’s protégés.

And the Argentine looked like he would live up to these expectations in the Pescara race, as in the second lap, the driver began charging through the field. Bordeau’s first victim was Love, who was now suffering from mechanical problems with his Cooper. Soon after, it was Scarfiotti’s turn, who after a brief skirmish, also gave in to the Argentine’s pressure.

On the other hand, Davis continued to open up the lead, unmolested by any of his pursuers. Bordeau’s Stanguellini looked like had reached the peak of his performance, and now seemed to be pleased with second place. And so was the script for the third and final lap of the heat, with Davis crossing the finish line first, 8 seconds ahead of the Argentine driver.

In third place was the Italian Ludovico Scarfiotti, who finished the race comfortably and carefree. That’s because his closest pursuer, the Cooper T52 of Briton Keith Ballisat, was almost a minute behind the OSCA driver. Rounding out the top-5 was another Italian, this time Renato Pirocchi, who had managed to remain firmly among the frontrunners, despite an apathetic performance in the race.

At 9:50 am, it was time for the second heat of the day. Australian Steve Ouvaroff, driving a Lotus 18/FJ, would have the honor of starting in first place, after reaching a time of 11min17s4 in qualifying. Due to doubts regarding Pirocchi’s time, Ouvaroff was credited as the fastest driver of the qualifying sessions, because of this mark.

Completing the front row were two Stanguellinis: one of the Frenchman Henri Grandsire, who had set a time of 11min26s4 and the other of the promising Italian Lorenzo Bandini, who was third with 11min29s8. Denny Hulme was close behind, managing to set the fourth best time, with 11min37s8.

Once the flag was lowered, it was Ouvaroff who jumped to the lead, using one of the best characteristics of the Norfolk based constructor in its own favor: the better weight distribution of the rear-engined Lotus. Grandsire tried to maintain his second position, with Bandini and Hulme fighting a beautiful duel for third. The New Zealander had managed to surpass Bandini during the climb to Spoltore, now relegating the Italian to fourth place.

But it didn’t take long for the leaders’ positions to change again. This is because before the end of the first lap, the gearbox on Ouvaroff’s Lotus broke, forcing the Australian to withdraw from the race. This promoted Grandsire to the lead, with Hulme in second and Bandini now in third position.

For much of the second lap it was Grandsire who led, with an average advantage of more than ten seconds over his closest pursuers. But again, bad luck struck a race leader, when one of the tires on the Frenchman’s car went flat. Still in the second sector, the only thing the driver could do was slowly head towards the pits, having to watch all his opponents overtake the struggling Stanguellini.

This left the contest between Hulme and Bandini open. At the beginning of the second lap, the New Zealander’s advantage was 3 seconds over the Italian. But after Bandini saw Grandsire’s slow car, the young Italian knew that now was the time to attack, to wrest the lead from his competitor.

Using the long straight between Capelle and Monte Silvano, Bandini made the final approach over Hulme. The slightly more powerful Stanguellini burned the small advantage that still kept the Cooper in the lead and, until the opening of the third lap, it was the Italian who was in front.

The Italian’s maneuver somehow affected Hulme’s performance, as throughout the third lap, the New Zealander was unable to answer Bandini. On the contrary, Hulme only saw the Stanguellini getting further away on the horizon, with Bandini crossing the finish line almost 20 seconds ahead of the New Zealander – to the delight of the Italian spectators.

The Italian Giancarlo Rigamonti finished third in the race, in an OSCA from Scuderia Sant’Ambroeus, with a deficit of almost a minute and a half to the New Zealand International Grand Prix Team driver. Even so, this was an excellent race for Rigamonti, who started in a humble 12th place. Even with the retirements of Grandsire and Ouvaroff, the Italian had to overcome much more experienced pilots on the track, such as Giancarlo Baghetti, Roberto Lippi and Rob Slotemaker, to get on the podium. It was certainly a memorable performance for Rigamonti.

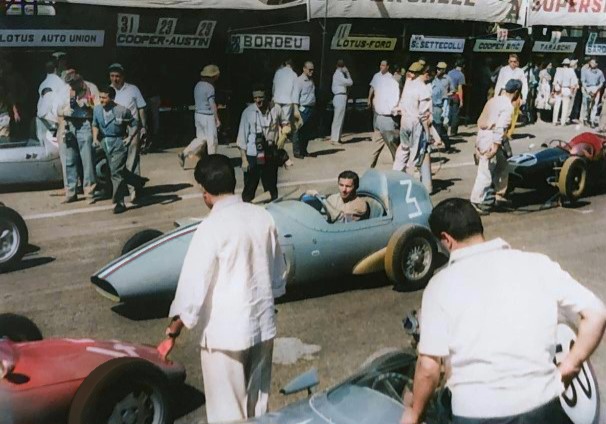

After a small break to evaluate the final heat times, the finalists lined up on the grid again at 11:30 am. In the end, 31 drivers managed to reach the minimum speed coefficient, including some who abandoned their qualifying heats (for example, Grandsire, who despite his problems and finishing on 18th in his heat, managed to get a place at the back of the grand-finale grid, due to the time achieved in qualifying training).

The first row of the grid was made up of representatives of cars from three different brands: first was Lorenzo Bandini, with his Stanguellini-FIAT; in second place, the British Colin Davis, with an OSCA-FIAT; and third, Hulme, with Cooper-BMC.

When the final flag of the XXVI Gran Premio di Pescara was finally dropped, the one who did best was Davis, who quickly took first place. Another one who had a happy start was Argentine Juan Manuel Bordeu, who, after starting in fourth, had already moved up to second before Montani.

Keith Ballisat, who was John Love’s teammate in the other Cooper of the Tyrrell team, took advantage of the circuit’s twisty first section, managing to execute some beautiful maneuvers over Scarfiotti, Hulme and Bandini. Until Spoltore, where the circuit’s first checkpoint after the start was located, Ballisat had become the immediate danger for Bordeau, with the two battling for second position. Hulme had dropped to 4th and Bandini had dropped to 5th within a few kilometers. But that didn’t shake the Italian’s confidence, who still remained in the first pack.

The section between Spoltore and Capelle presented new changes in the face of this group. While Davis opened up in the lead, Hulme had recovered from the start and the loss of positions, managing to re-overtake both Bordeau and Ballisat, now moving up to second position and now setting his sights on the race leader.

Ludovico Scarfiotti had entered the fight, managing to climb a few positions thanks to an overtake on Bandini and then another maneuver on Ballisat, on the long straight between Capelle and Monte-Silvano, where the FIAT engines spoke louder than the first-generation BMCs.

At the end of the first lap, we had: 1st Colin Davis (OSCA); 2nd Denny Hulme (Cooper); 3rd J.M. Bordeau (Stanguellini); 4th Ludovico Scarfiotti (OSCA); and 5th Lorenzo Bandini (Stanguellini). Davis had built up a lead of almost 11 seconds over Hulme, but the New Zealander was now in hunting pace, inexorably closing in on the Brit.

Another one who was doing his part was Grandsire, who after starting at the back of the field, had already moved to the 13th position. John Love was also giving everything he could, as the Rhodesian was already on his teammate’s heels at the start of the second lap. And it didn’t take long for the African driver to overtake Ballisat, now taking 6th position.

After this overtake, the order of the top six remained unchanged for the remainder of the lap. The only clear difference was that Davis’ lead over Hulme had shrunk marginally, falling from 11 seconds to 8.

On the third lap, the biggest attraction was the duel between the promising Bandini and Scarfiotti, for fourth position. In the end, Lorenzo managed to overcome his opponent, and he was now one step away from the podium. Even so, overtaking was not a good Italian move, as the duel with Scarfiotti consumed precious time, something that allowed Love to get closer.

Meanwhile Hulme continued his quick pace, further closing the gap between himself and Davis. At the start of the fourth lap, just 2 seconds separated the Kiwi from the Englishman.

The fourth lap was John Love’s lap: the Rhodesian’s Cooper seemed to be at home on this final race at the Pescara circuit, as the driver managed to make two beautiful overtakes in succession over Scarfiotti and Bandini. The Italians tried to react on the long straights of the track, but Love held off the duo’s pressure.

J.M. Bordeau kept making constant laps, and continued in a comfortable third place. On the other hand, Colin Davis used this lap to give a clear answer to Hulme, managing to expand the advantage again, which was now just over 3 seconds.

The fifth lap was used for the drivers to consolidate their positions, with Davis again opening up a comfortable lead over Hulme: the few seconds of the last couple laps had now turned into an advantage of almost 9 seconds.

But on the sixth lap, Davis’ problems began to appear: the Brit’s OSCA began to suffer from excessive brake wear, and at the entrance to the curves, the car no longer performed as well as in the previous laps. Hulme tried to take advantage of his opponent’s problems, and close to Capelle, the driver had attacked and overtaken Davis.

However, the OSCA was still healthy on the straights, and the small power margin of the FIAT engine over the BMC was enough for Davis to regain first position at the opening of the last lap. But it was close call to Davis, because Hulme had managed to set the absolute record for FJ cars on the Pescara circuit in this lap: a magnificent time of 11min10s4

Just tenths of a second separated the two drivers as they began the gentle climb between Montani and Spoltore. Davis still in the lead, with Hulme in his rear mirrors. It seemed that the Briton had held off Cooper in the section where it had the biggest advantage, but his hope of winning the race was quickly dashed.

It all happened on the tight Capelle curve, where Davis lost control of his OSCA and ended up on the banks of the circuit. The car’s brakes had locked and the British had just become a passenger in his own vehicle. Hulme, who had nothing to do with the driver’s error, took 1st position, just a few kilometers away from the checkered flag.

Davis quickly tried to get back into the race, as the car had only suffered slight damage to the front. But it took a few minutes before the driver managed to get back on the track – and in the end, Davis, who had led 95% of the race, only finished in a disappointing 7th position.

The person who was grateful for all this was New Zealander Hulme, who had no trouble in the final kilometers, crossing the finish line with a total time of 1h19min18s. Second, to the delight of a certain J.M. Fangio, who was in the stands of the Pescara circuit, was an exultant and surprising Juan Manuel Bordeau, who had finished just 9 seconds behind the Kiwi.

Completing the podium was John Love’s Cooper, who, after a very solid race, had given an excellent business card about the qualities of drivers from the African continent. The Italian duo of Ludovico Scarfiotti and Lorenzo Bandini gave final numbers to the five best classified in the race.

THE ‘ENDS’ OF PESCARA

The result was spectacular for Denny Hulme: on his first European tour, the driver had already written his name in history, winning one of the most traditional motorsport trophies of the 60s, in front of an audience of almost 200.000 people (a number estimated by newspapers of the time). This would suit as the first indication of the driver’s future victorious career on the international motorsport scene.

Furthermore, Hulme would enter the folklore of the Pescara circuit for another reason, still unknown in the midst of the euphoria of the 1960 victory: it had been decided that in 1961, the race would be part of the World Sportscar Championship (WSC), contested only by Touring and Sports cars.

In 1962, however, the Pescara circuit was finally condemned as unfit to serve the purposes of a sports venue, and the track’s license was revoked by both the F.I.A. and the A.C.I. (the Italian motorsport federation). This meant that Hulme was the last driver to win a single-seater race at the legendary circuit – something that would certainly be a milestone and a good memory in any driver’s career.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

- Italian Newspaper Corriere dello Sport: edition of 17th August 1960

- Italian Newspaper La Gazzetta dello Sport: editions of 17th and 18th August 1960

- Italian Magazine l’Automobile: edition of 21th – 28th August 1960

- Italian Magazine Quattroruote: edition of September 1960

- Swiss Magazine Revue Automobile: edition of 18th August 1960

- Special thanks for Automobile Club Pescara (A.C.P.), who made available a large part of its collection for the construction of the text.