The year of 1970 would bring new winds to all motorsport in the Southeast Asia and Oceania region. New Zealand and Australia, which were the region’s main exponents in this sporting discipline, had promoted a major and risky change, by substantially modernizing their sporting regulations, which had been in force since the mid-1960s. Both countries were so preponderant in this macro-regional scenario, that the changes promoted by them would impact not only the Tasman Series, the New Zealand Gold Star and the Australian Golden Star, but also, soon spread to all nearby countries, promoting a revolution on the tracks that had not been seen in the region for a long time.

The main one, without a doubt, was the official replacement of the “Formula Tasman”, which since 1964 had set the tone for the Formula racing in the region, by the “Tasman Cup” regulations. The old regulations, which stipulated that only engines ranging from 1.6-liter to 2.5-liter could compete in ranked single-seater events in Oceania, began to lag behind, largely due to developments in the area around the combustion engineering that had taken place since the mid-1960s.

Besides that, Australian and New Zealand promoters seized on other more tangible justifications to find a replacement to the old regulation: the FPF, FVA and 1st gen-Twin-Cams engines, which were the main representatives of classic “Formula Tasman”, had arrived at the end of their life cycle, being totally obsolete by late 60’s standards, especially if compared to the new-generation engines present in the main automotive centers around the world. The costs of maintaining such devices were no longer compensated by the return of events, and the small Aussie and Kiwi teams suffered from an increasingly lean budget to compete with the European giants, who always attended the Tasman Series with new and superior power plants.

After experiments carried out between 1968 and 1969, an agreement was reached between the New Zealanders and Australians: from 1970 onwards, the Formula 5000, which had become extremely popular in the USA and UK, would be included in both New Zealand and Australia calendar, assuming the role of the main regional category for single seaters and replacing the old regulations. This, it was expected, would increase the level of competitiveness of the championships, reducing costs and providing teams with the chance to arm themselves with more powerful, reliable and cheaper engines.

So, the venerable 1.6-litre Ford engines would give way to the monstrous Holden and Chevrolet V8s, up to 5 liters. The Cooper, Lotus, Ferrari and Brabham chassis, which had dominated motorsport in Southeast Asia until now, began to disappear, as they would now have to share their space with ‘younger players’, such as Surtees, Lola and Elfin, which, in a few years, would become the most popular names on race tracks throughout the region.

Although technically accepted and put into practice in 1970, the “Tasman Cup” regulations would only be officially enforced in the beginning of 1971, with a well-defined categorization of accepted cars and engines. Furthermore, the implementation of the new agreement stipulated that drivers would have a period of one year, from the start of the 1970 season, to have 2-valve engines installed in their cars. All 4-valve engines that still existed on the grid from 1971 onwards would be permanently downscaled to the National Formula – an equivalent to the American/Canadian Formula B –, which, from 1970, would house the remaining 1.6-liter cars still on the grid (the vast majority of them equipped with Twin-Cams post-1967).

So, 1970 ended up becoming a year of transition, where the most diverse generations of engines and cars coexisted. It was as if, during a year, a great Formula Libre season developed throughout the region, with the regulated championships in Australia and New Zealand integrating, in a primitive way, with the various races spread across other countries in the region: from Indonesia, passing through Singapore, Malaysia and Macau, and going as far as Japan.

One of the most spectacular stories from that peculiar year was the performances of Kiwi Graeme Lawrence. Driving a 2.4l Ferrari Dino 246T, it seemed that the driver would have no chance against the swarm of 5-liter “brutes”. But, defying all odds, the driver proved that the nimbler cars could still be the ones that delivered the biggest performances. The legend of Lawrence’s Ferrari was one of those picturesque moments in automobile history, of first times and persistence, of opportunities taken and preparation, believing that the machine-driver combination would come into sync and would be enough to overcome the adverse factors that existed.

It was the last gasp of the 60’s, of the past that had been magnificent for the development of motorsport in the Asian-Pacific zone. And it was also the first sign of the new features the future would bring, some of which were demonstrated in the first real test of the new rules, in the 1970 Tasman Series. New faces, new voices, new sounds…. this was the setting of Asian motorsport on the eve of the 70s.

1970 Singapore GP

After the great balance of the Tasman Series, which ended just a month before, it was expected that a large contingent of drivers who participated in that series would also participate in what was one of the great automobile events of Southeast Asia: the Singapore GP. And a great show was promised, especially with the tone of revenge that was publicized by the press: would the runner-up of the Tasman Series, Frank Matich, give the payback on Graeme Lawrence?

And the lift-off over the Java Sea really happened. The main drivers to confirm their presence were Graeme Lawrence, Frank Matich, Kevin Bartlett, Malcolm Ramsay and Albert Poon; in addition to them, another eighteen pilots were registered in the GP’s preliminary list.

The main attraction was, of course, the newly crowned Tasman Series champion (and also 1969 Singapore GP champion) Graeme Lawrence and his Ferrari Dino 246T Tasman. With chassis number #0008, this was the same car that was “lent” to Chris Amon to compete in the Tasman Series one year before.

By itself, this car already had a rather peculiar story. It all started when Scuderia Ferrari loaned two chassis to Chris Amon to compete in the 1969 season of the Tasman Series: the #0008 itself, in addition to the #0010. With this loan, conditions arrived: the first was to have another official Ferrari driver in the second car; and the chosen one was Derek Bell. Another point is that the car would not be officially managed by Maranello, but by Amon himself, for the duration of the championship – but the results achieved would be attributed to Ferrari (hence the name Scuderia Veloce).

The cars themselves were basically the same as those that contested the 1968 European F2 season and the Argentine F2 Temporada later that the year (the biggest differences being the engine, modified to a 2.4-liter Tasman, and the expanded power boost, up to 285 bhp). Even with these modifications, and the great results achieved by the car in the last races of 1968, Chris Amon had doubts if this would be enough in 1969. To his own surprise, it was, and Amon himself became champion of the 1969 Tasman Series. After this victory, the car did not even return to Europe. Amon sold chassis #0008 directly to Graeme Lawrence, who continued Ferrari’s legacy in Australia and New Zealand after the last factory-backed effort of the Maranello team in Oceania.

Lawrence’s biggest challenger was the Australian Frank Matich, who had been runner-up in the 1970 Tasman Series (the difference between Matich and Graeme was only 5 points at the end of the championship). He would drive a McLaren M10A (chassis number #300-10), built to Formula 5000 specifications with a new and powerful 5-liter Traco Chevrolet V8 engine. With strong sponsorship from the Rothmans cigarette brand, Matich was arguably the main threat to Lawrence’s victory.

Kevin Bartlett was also another standout in the 1970 Tasman Series and was one of the big favorites for the win. Driving an Australian-built Mildren-Mono (nicknamed Yellow Submarine) powered by a Waggott TC4V 2-liter engine, he had achieved a string of good results earlier in the year, culminating in his victory at the Warwick Farm “100”.

Even though he had very little experience in single-seaters, Australian Malcolm Ramsay promised to be one of possible surprises in the race. Ramsay had gained his fame through his good performances in touring car races across the Southeast Asian and, when the driver received an invitation to drive an Elfin for the Harrison Racing team, this was obviously a testament to his qualities on the track. The car he would drive was an Elfin 600C (ex-Steve Holland), equipped with a 2.5-litre Repco V8 engine.

The last of the highlights was Albert Poon, a well-known figure on the Southeast Asian GPs, mainly for his appearances in Macau. Poon had one of the most advanced cars on the grid: the Brabham BT30. This model, which was one of the most used Formula 2 cars of its time, and well regarded by the European F2 teams between 1969 and 1970, would now have the chance to demonstrate its potential in the lands of the East. Specifically, Poon’s car was an ex-Frank Williams, having been driven by Piers Courage and Richard Attwood in several races in Europe during 1969. At the end of that same season, the car was sold directly to Albert Poon.

The chosen scenario for all these pilots to show-off their skills would be the infamous Thomson Road Circuit, inaugurated in 1961 for the Orient Year Grand Prix; and which quickly became one of the most prestigious events in the Formula Libre racing series in Asia. When Singapore became independent, the venue gained even more prominence and importance, and in 1966 it was rebranded the Singapore Grand Prix.

The circuit, 4.865-meters-long, gained fame for its winding, fast and extremely dangerous layout. The track started at the Thomson Road, nicknamed “the Murder Mile”, which, in normal work days, was (and still is) one of the most important roads in Singapore. The Mile was split in two, by the Hump, a fast right uphill turn, with a false apex on its inside.

The second part of the Mile ended abruptly at an elbow, known as the Circus Harpin. After this turn, the drivers began a slight access, that led to the most sinuous part of the circuit: first the 4-sequence of bends known as “The Snakes”, then the “Devil’s Bend” curve; this was the entrance to another long radius turn, which was bound for the Long Loop and Peak Bend turns. After that, the pilot was almost at the entrance to the pits and at the end of the lap, which was outside the Range Harpin.

For the 1970 event, an important change had been made to the layout: the temporary chicane that existed at the end of Thomson Road, which served to reduce the speed of vehicles before entering Circus Harpin, had been definitively eliminated. This considerably increased the average speed per lap of the cars – but also increased the risk of a serious accident at the end of the “Murder Mile”.

The drivers began arriving in Singapore on March 25th, and on the next day (26th), activities began on the dreaded Thomson Road circuit. Right in the first track reconnaissance session, Graeme Lawrence made it clear that he would not give his opponents any chance. He pulverized the track record, set the previous year, lowering it by 1.8s, and establishing a time of 1m57s8/10.

With less than a second difference and setting the second fastest time, came Kevin Bartlett and his Mildren Mono Alfa Romeo V8. And the dominance of the Tasman Series drivers did not end there, because Max Stewart, in a characteristic Mildren “Rennmax BN3”, equipped with a Waggott TC4V engine, managed to snatch the third position, closing a lap in 1m59s6/10 (same time as the 1969 record). With two drivers beating the track record and another equaling it, it was soon demonstrated that the 1970 edition would be one of the fastest in the history of the circuit.

And that speed almost proved fatal on the first day, when Frank Matich lost control of the car at more than 257 km/h and ended up in a tree, near a bus stop. According to what the pilot reported at the time, when leaving the first part of the Thomson Mile and going over the Hump, the car went out of control due to the track condition, which was extremely slippery as a result of a light drizzle that was falling on the circuit. The driver wasn’t able to react fast enough, and Matich simply became a passenger in his own car.

Fortunately, the pilot was completely unharmed from the accident; the same could not be said of the McLaren, which had the front almost ripped off due to the impact. At the time of the accident, the driver had the fifth best time, but the crash basically ended Matich’s chances of fighting for a best spot on the grid. It was now up to Rothmans Team mechanics to try to get the car in the best possible shape for the next day’s official qualifying sessions.

The 27th arrived and with it, a phenomenon so common on the island of Singapore: the traditional tropical storms in the afternoon. Weather conditions became so adverse (even by local standards) that all activities on the circuit had to be canceled. The one who was grateful for the downpour was undoubtedly Frank Matich, who had already accepted his fate of starting in the last position of the grid; but now, with one more day to prepare the car, the pilot believed that his mechanics could put the McLaren in conditions to dispute the victory again.

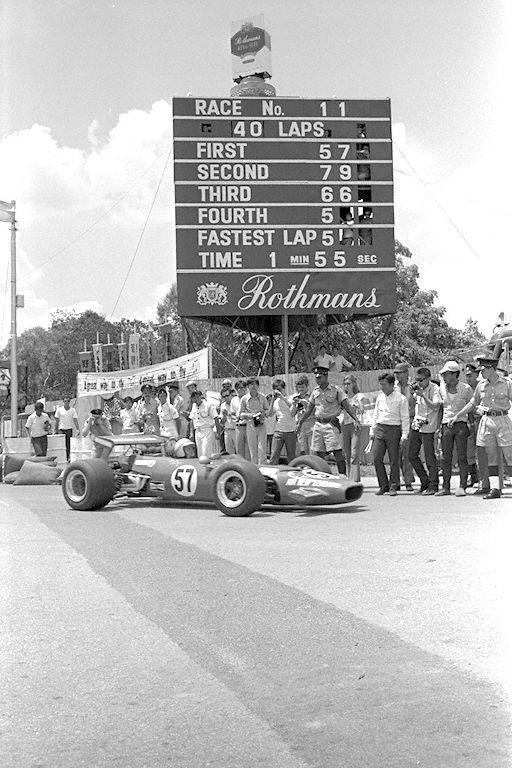

The 1970 Singapore GP would be held in 2 heats: the first, on Saturday (28), would be sort of a ‘sprint race’, with 20 laps. On the following day, Sunday, the other 40 laps would be carried out, making a total of 60. For the final result (and the title of Singapore GP winner), only the outcome of the second heat would be taken into account.

Some of the drivers were not very fond of this dispute format, mainly because it favored certain cars over others. For example, Albert Poon highlighted how his Brabham would have an advantage over the monstrous Australian engines, if the dispute was held in only one-full heat: “My car is specially fitted with a 21-gallon tank which is more than sufficient to last the race without refueling” (The Straits Times, March 1970).

Liking it or not, the riders lined up on the grid for the first heat. The starting order was defined by the times of the free sessions: therefore, Graeme Lawrence and Kevin Bartlett were the ones who opened the grid, followed by Stewart, Matich, MacDonald and Poon.

With the checkered flag lowered, the cars shoot off on the 4,865-meter circuit. It quickly became clear that the fight would be between the two Italian-made engines: Bartlett’s Alfa and Graeme’s Dino/Ferrari. But Graeme had a scare on the second lap, when the driver missed the breaking point on the Range Harpin and ended up on a spin. Nothing to worry about, as both the car and the pilot emerged unscathed; so, Graeme resumed his hunt for Bartlett.

Right behind, a compact group was formed, involving Mike Heathcote (Singapore), John MacDonald (Hong Kong), Albert Poon (also from Hong Kong) and Hengky Iriawan (Indonesia). On the second lap, these drivers would provide another one of the remarkable and infamous moments in the history of the Thomson Road circuit.

On the Thomson Mile, almost in the same place as Matich’s accident, Mike Heathcote (in a 1.6-liter Brabham-Ford Twin Cam BT2) was trying to overtake Albert Poon (Brabham-Cosworth FVA BT30). Both drivers, in speeds above 250 km/h, were in an intense fight for positions and when Heathcote tried finally the overtaking maneuver, he misjudged it.

The pilot lost control of the car in the inside part of the feared hump, spun and went straight into the trees on the outside part of the track. The car broke in two due to the collision, with the main body resting on a small creek, a few meters away from the track, and the engine block disappearing in the middle of the dense forest that surrounded the circuit. Again, to the relief of the audience, the pilot left the accident almost unharmed.

In an interview, a few days later, Heathcote described the accident: “I fought to correct that by turning out of the corner, but my back wheels caught the verge […] The car spun right round, hit the right-hand curb and went up in the air. I saw white and yellow flashes and there was a tremendous noise – everything seemed to be happening in slow motion” (The Straits Times, 5th April 1970).

But as such accidents were common at the circuit, the race went on. Frank Matich, who owed a lot to the Rothmans team of mechanics after the superhuman work of rebuilding the car in just two days, looked like he could get a reasonable finishing position in the Saturday heat race, to give all he could on Sunday. But that idea soon fell apart. On the third lap, the Australian faced his first problem, with a tire puncture. No big deal, this being quickly circumvented. But five laps later, a terminal problem meant the end of any hope, as the engine choked and gave its last breath.

Another one who was also struck by bad luck was Max Stewart: on the same lap that Matich made his tire change, Stewart’s Mildren “Rennmax BN3”- Waggott also refused to continue going forward, since his engine also had terminal problems. In the end, the pilot, who had scored the third best split time in midweek practice session, had to abandon the race.

So, with two of the top four drivers out of action, the battle for the victory would be decided between Bartlett and Graeme. Lap after lap, the duo pulled further away from the field, with both lapping the rest of the grid. With great skill, Bartlett used the power of the Mildren-Alfa V8 against the nimbler Ferrari. And so it was, managing to slowly build-up an advantage, which reached nine seconds when the final checkered flag dropped. In addition to securing pole position for Sunday and relegating Ferrari to second place, Bartlett set a new track record: 1m55s8/10.

One lap behind, therefore, came the other classifieds: John MacDonald (Schomac Racing/Brabham-Cosworth RVA BT10), Albert Poon (Privateer/Brabham-Cosworth FVA BT30), Hengky Iriawan (Racing Services/Elfin-Cosworth FVA 600CS), Chong Boon Seng (Privateer/Lotus-Cosworth 41) and Steven Kam (Privateer/Lotus-Ford 23b Twin Cam).

But there was no time to celebrate and the next morning the cars lined up again on the starting line, for the race that would really define the winner of the 1970 Singapore GP.

The grid was slowly decimated by the fatigue of the long week that preceded this heat: among the drivers who did not show up on the decisive day, of the cars that were victims of accidents, mechanical problems and other failures, only 10 would start on Sunday. Even with this number much lower than expected, that did not stop the public from invading the Thomson Road circuit. According to some press reports at the time, a crowd in excess of 100,000 people lined up on the sides of the track on that Sunday morning.

Flag dropped, and the grid quickly pulverized into two small groups: Bartlett, Lawrence and Max Stewart (who had managed to fix his car overnight) took the lead, while MacDonald, Poon and the other drivers fought for the middle positions of the grid.

In the first laps, Graeme Lawrence spun his car again. But, as if the script was repeating itself, it was nothing that affected the performance of the pilot. In less than five laps, the driver and his Ferrari had already reached the top two again; and on the tenth lap, Lawrence had already recovered the second position, when he overcame Max Stewart.

And Graeme’s momentum didn’t stop there. With the very strong race pace that was being set by Bartlett, the Ferrari became the only car that could catch the Mildren-Alfa. And so began the chase, which would last for most of the race. Bartlett piled up faster and faster lap times, managing on the 27th lap to set a new track record: 1m55s5/10. Graeme answered, keeping close to the pilot of the Mildren.

Max Stewart sought to protect himself, accepting the third position – he didn’t have the car to compete with the leaders, but also, wasn’t threatened by the drivers that came further behind. But even going at a cruising pace doesn’t mean reaching the end of the race: during one of the laps, the pilot became distracted in the Long Loop, where lost control of the car and ended up in the middle of the trees. End of race and goodbye podium.

So, the race was summed up between the Bartlett vs. Lawrence duel. And luck again laughed to the last. When the Ferrari driver had reduced the gap to less than 2 seconds, Lawrence saw when Bartlett pulled to the pits, on the 37th lap. He couldn’t know it, but the Australian’s Alfa engine had overheated, due to the sweltering conditions of Singapore.

So, without competition and with only three laps to go, the driver had no trouble leading Ferrari to another victory (the second with him at the wheel, if you count his victory in Levin). Two laps behind came the drivers who would complete the podium: John MacDonald and Albert Poon, second and third, respectively.

Graeme Lawrence was crowned winner of the Singapore GP once again. The pilot had made a high stakes gamble on the race: according to what he told in an interview to The Straits Times a month later, he managed to take only one chassis and one engine to Singapore! Because of this, the pilot accepted second place in the first heat, and then waited for the opponent’s error (or car failure) in the second. We can say, apparently, that the strategy paid itself off in the end…

1970 Selangor GP

3 days after the race in Singapore, the drivers headed into the second of the Asian legs of the Formula Libre. The destination was now the Batu Tiga circuit, located 25 kilometers west of the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur. Opened just 3 years earlier, the Batu Tiga circuit (or Shah Alam, as it would later become known the site) had a peculiar history.

The track was created with the aim of promoting high-performance motorsport in Malaysia, in a more suitable location than the primitive street circuits that prevailed, until now, in the region. To this end, the mission of designing a track was given to track designer John Hugenholtz, one of the best-known names when it comes to this matter. The Dutchman’s contributions were felt in different parts of the world, being responsible for designing racetracks from Japan (Suzuka), through Finland (Ahvenisto), Belgium (Nivelles and Zolder) and Holland (Zandvoort), and crossing the Atlantic, to the United States (Ontario Motor Speedway).

The layout designed by Hugenholtz for the Malaysian promoters was 3,380 meters long, with a total of 12 curves and 2 long straights (the finish/start, and what became known as Shell Straight), and proved popular with drivers already in the first race held at the venue in 1968. Since then, Batu Tiga has become a traditional Formula Libre stop in Southeast Asia, regularly hosting two Formula Libre events per year at the venue (the Selangor GP and the Malaysian GP).

And the 1970 edition was eagerly awaited by Malaysian organizers and spectators: after Graeme Lawrence’s superb performance in Australia and then in Singapore, would the pilot be able to maintain his high level in Malaysia as well? There was no shortage of worthy opponents, as most of the pilots who took part in the event at Thomson Road also followed him to Selangor.

In addition to Lawrence, Max Stewart, Albert Poon, Malcolm Ramsay and Hengky Iriawan gladly accepted the invitation to participate in the race. The big absences would be Frank Matich and Kevin Bartlett: Matich, after the numerous mechanical problems faced by his McLaren during the weekend of the Singapore GP, had decided to skip the leg in Malaysia, to focus on preparing his car for the Australian Gold Star. And even though Bartlett was on Batu Tiga’s pre-entry-list, he also decided at the last minute to decline participating in this race, to also focus on the upcoming Australian championship.

Although Albert Poon and Hengky Iriawan had already won races there (in the 1968 Selangor and Malaysian GPs, respectively), both had little hope of facing Lawrence, Stewart or Ramsay on equal terms. In an interview for the Malaysian press, Hengky himself highlighted that he would have difficulty fighting a long-term battle for leadership, saying that at most “I will be close behind the leaders”. (The Straits Times, 2nd April 1970)

Another fact that contributed to Graeme Lawrence’s favoritism in the race, in addition to his Ferrari-Dino, was that the driver was already a well-known figure on the Batu Tiga circuit, having competed in some races there. As his best result, in the 1969 edition of the Selangor GP, the driver even managed to take home the victory trophy, in the wheel of a McLaren M4A.

And on the first day of free training, held on April 2nd (that is, just 4 days after the final flag in Singapore), expectations seemed to come true. Although workers were still present on the track, carrying out the final repairs to the circuit’s floor, Hengky Iriawan, Malcolm Ramsay and Graeme Lawrence took the risk of taking a few laps around the circuit.

Hengky and Ramsay did no more than 15 laps each, with the Indonesian driver being the fastest of the pair, clocking a time of 1m32s. Not bad for a car that still ran with Singapore gear ratios – something that certainly deserves clarification, given that the characteristics of the Batu Tiga and Thomson Road circuits were completely different, which certainly required a different adjustment. On the other hand, Ramsay wanted to have a good session, but problems with the fuel pump in his Elfin-Repco basically forced the driver to drive slowly around the track.

But no setback seemed to bother Graeme Lawrence: despite the driver also racing a car tuned for the winding streets of Singapore, the Australian was devastating on the fast Malaysian circuit, with Graeme soon overturning the track record. The driver managed to set a time of 1m20s9/10, just over 3 seconds faster than the mark set by Roly Lewis the previous year. Although it could not be considered the official track record (because this was an unofficial training session), Lawrence had proven that he would not come to Malaysia for tourism.

The following day, the first official training session for the Selangor GP. Once again, Lawrence proved to be going through a magical phase, because even though he was unable to achieve times as spectacular as those of the previous day, he continued to be fast on the track, having constant laps close to 1m25s. Malcolm Ramsay improved his performance, despite only running 10 laps around the track. A time of 1m26s placed him in second place overall in the classification.

Friday’s session was short for the drivers, given the tight schedule of events for the weekend (which would feature not only the Grand Prix for the F. Libre, but also races for touring cars and motorcycles). Because of this, any minute was essential, and any delay was catastrophic. It was this feeling that had reached Max Stewart in the Thursday and Friday sessions, as the driver’s Mildren “Rennmax BN3” – Waggott had spent these two days exclusively in the team’s garage, due to constant mechanical problems.

For Stewart, hope laid in the final training session, which would be held on Saturday, between mid-morning and early afternoon. The mechanics from the Alec Mildren Racing team worked intensely on the car during Friday and, before Saturday arrived, all the car’s mechanical problems had already been resolved – theoretically speaking, as only on the track would it be known whether the efforts would be rewarded.

Once again, the drivers took advantage of the hours of training to make the final adjustments and improve their times. Graeme Lawrence continued to lead the timesheets, followed by Malcolm Ramsay. Hengky Iriawan had dropped to fourth after a good lap set by John MacDonald and his Brabham-Cosworth RVA BT10. However, the attraction was undoubtedly Stewart, who was surprisingly fast. The Australian started to pile up quick times until he reached the mark of 1m24s8/10.

This meant that Mildren was leading the field, with a time just tenths lower than that achieved by Graeme. However, the driver and his Ferrari didn’t give up that easily, and Lawrence spared no effort to regain first place. But in the end, that wasn’t enough; and Max Stewart would have the right to start from the grid position of honor in Sunday’s race.

A cloudy Sunday had descended on the circuit, with intermittent rain circulating over the Batu Tiga circuit. The day’s agenda began with a bicycle race, later progressing to a Club Race for cars, and with open events for motorcycles (two secondary events for smaller-displacement motorcycles, which would culminate in the Selangor trophy for production machines). The last race of the day and weekend would be the Selangor GP for Formula Libre cars, representing the climax of the event.

It was only at 4:30 pm that the teams were allowed to line up their machines on the circuit’s starting grid. Just over 10 drivers were able to compete in the race, due to the same problems that had caused casualties on the Thomson Road grid a week earlier. The wear and tear on the cars were above normal, due to the humidity and heat that prevailed in this part of the world. Parts frequently broke, in addition to other mechanical problems, which required greater technical assistance than the one available on the sites.

In addition to the drivers mentioned above, others who were present at the race were Chong Boon Seng (privateer/Lotus 23b, due to having crashed his Lotus 41 in the final race in Singapore) Lional Chan (E.L. Chan/Merlyn-Ford Mk7 F3), Jan Bussell (Team Torque/Brabham BT14 Twin Cam), Steven Kam (privateer/Lotus-Ford 23b Twin Cam), Ray Jones (privateer/Cooper-Ford) and David Coode (Team Tuppence/Tuppence F. Ford).

The flag was lowered, and the cars zipped across the track, in the first of the 60 valid laps of the Selangor GP. Stewart tried to secure the first position, followed promptly by G. Lawrence and M. Ramsay. Behind, MacDonald, Iriawan, Poon and Bussell formed a second group, which was promptly fighting an interesting battle for fourth place.

The rain started to get more intense from the second lap onwards, but that didn’t stop Albert Poon from performing a beautiful overtaking maneuver on the Indonesian Iriawan. The pilots took their machines to the extreme, in a track condition that became increasingly dangerous.

And on the third lap, the first victim of the rain – and it could be none other than the leader himself, Max Stewart. When the driver reduced his speed to make the slow Rothman’s Corner (the last corner of a lap of the original Batu Tiga circuit), the Mildren “Rennmax” locked the wheels and the car unexpectedly spun. The machine only stopped in the escape area on the outside of the curve.

Although it was not a serious accident, Stewart soon realized that there was something wrong with the car: the back of the vehicle was very loose. The driver then decided to quickly go to the pits, and the Alec Mildren Racing mechanics soon discovered that the vehicle’s rear suspension had given way. It was the end of the Australian driver’s chances of victory.

Meanwhile, Graeme Lawrence took the lead, followed by Malcolm Ramsay. The New Zealander and the Australian would begin to definitively distance themselves from the rest of the field, leaving an open fight for third position. MacDonald, Poon and Iriawan looked like the strongest contenders in this contest, with Jan Bussell already losing a bit of touch with this battle.

Before 10 laps, Hengky had managed to overtake Poon, once again taking a position in front of the Hong-Kong driver. Despite the new track position, Iriawan was unable to capitalize on his success, as, on the 13th lap, the driver lost control of the car in the Lucas Loop (the curve just after Shell Straight), also going for a trip through the escape area of the track. Luckily, Hengky didn’t have as serious mechanical problems due to his ‘shortcut’ as Stewart, and, after a few minutes stopped in the pits, the Indonesian returned to contention.

At that moment, both Lawrence and Ramsay were already starting to face the first stragglers on the track. This, combined with the heavy rain that fell on the track, made the race a challenge of attention, patience and calm, avoiding unnecessary risks.

Despite this, other drivers fell into the trap of the treacherous track, such as Lional Chan. With 1/3 of the race having passed, it was Malcolm Ramsay’s turn to also be fooled by the cunning Batu Tiga circuit. The Australian’s accident was almost a copy of the one that involved Stewart, laps earlier: at the same Rothman’s Corner, the car spun and ended up on the side of the track. The left rear suspension of Ramsay’s Elfin-Repco was completely destroyed in the accident; and the only thing the driver could do afterwards was take his car directly to the team’s garage.

This left Graeme Lawrence in a comfortable position, with the Kiwi at this point already one lap ahead of the now second-placed John MacDonald. With no major threat nearby, Lawrence and his Dino 246T circulated at a steady pace, with the New Zealander more cautious to avoid being the next victim of the puddles of water that increasingly accumulated around the circuit.

And so the laps went by, with no major movement in the field. Although some drivers withdrew from the race before the final laps, none of them would interfere with the final track positioning, as, at that point, most of the leaders were already very close to the final flag.

After 1h45m45s, Graeme Lawrence crossed the finish line first, two laps ahead of second place John MacDonald. Giving final numbers for the podium was Albert Poon, 3 laps behind Lawrence in the final standings. The only two other drivers who completed the minimum number of laps were Jan Bussell, who finished 4th with 54 laps, and Hengky Iriawan, in 5th position with 49 laps completed.

The Southheast Asian Championship: A Proposal That Never Took Off

The expansion of motorsport in Southeast Asia really began to gain momentum in the late 1960s, when the national GPs in Macau, Singapore and Thailand began to be attended more regularly by drivers not only from those nations, but also experienced representatives from Australia, New Zealand and Japan. The ‘invasion’ of these nations in the entry-lists of these events was extremely beneficial, since such events, which only occurred on a micro-regional scale, began to have a certain international tone in their proposals.

Drivers such as Graeme Lawrence, Max Stewart, Roly Levis and Mamoru Moriwaki were key players in this process of international expansion of Southeast Asian racing, demonstrating that motorsport and high-performance motorcycling no longer existed only in the world reference centers of these categories. This process of assimilation and acceptance developed strongly until the final moments of 1969.

And as the new decade unfolded, the ground was ready for the next big step: the creation of a unified championship, which would involve these various peripheral nations of world motorsport. Such a championship, it was hoped, would occur in a symbiotic manner with other more consolidated events in Oceania and Japan, building an integrated calendar that would cover the entire trans-Pacific zone.

For this reason, it was expected that the championship would be called either the “Pacific Series” or the “Pacific Motor Racing Championship”. The movement to create such season gained momentum after the 1970 Singapore GP, with important drivers from the region giving their unconditional support to the project.

For example, Kevin Bartlett, in an interview, said that: “Most of them (pilots and teams) are not keen to spend big sums of money just for one race. If you have four held in a row, they will certainly be attracted.” Frank Matich was also another who took a stance on the matter at the time: “If the idea of the Far East circuit failed, then Singapore should go ahead to arrange a series of three races with Malaysia. This could in time join the Tasman Series”. However, the person who seemed to be the most enthusiastic supporter of the idea was Graeme Lawrence: “There is a definitive need for such a motor-racing championship in this region […] the GP drivers are hungry for experience and the Pacific championship could be the answer” (The Straits Times, interviews taken on March 1970 and Abril 1971).

1971 was a key point in the history of the proposed series: although serious talks took place between the various national motorsport entities involved, little was achieved in concrete terms. One of the main obstacles was the racing formula: Australia and New Zealand had definitively embraced the F5000, while Southeast Asian countries were still betting on the 1600cc format. This attitude forced teams and drivers to have two different combinations of cars/engines, for two completely opposed “Formulas”.

This was a point that could never be overcome at the negotiating table and that definitively stalled the “Pacific Series” project. It was only between 1975 and 76 that an integrated championship could be put into practice in the region, using the Formula Atlantic regulations – and only thanks to the strong sponsorship of the Rothman’s cigarette brand.

Despite this audacious move, this would prove to be an ephemeral measure, as the ideal timing had already passed: the Tasman Series, which was the main highlight in the Pacific region, was by mid-70’s in sharp decline, far from its glory days of the 60s and early 70s – and, in 1976, the unified “Series” era had been officially relegated to the pages of history, when Australian and New Zealand racing events were finally desegregated. The Macau GP, which was without a doubt the most prestigious race in the Asian-Pacific zone, was also at its lowest point in popularity, with the organizers struggling to put together the bare minimum number of cars in the grid of the Formula races.

So, it was no surprise that when Rothman’s withdrew its support of the organization at the end of ’76, the Southeast Asian racing became once again a pout-porritt of scattered events, being mostly frequented by pilots of rather dubious quality. Thus came the end of a dream, which, as promising as it seemed, would never be completed to its full potential.

Acknowledgments

- Singapore Newspaper The Straits Times: editions from 24th March to 20th April 1970

- Singapore Newspaper The Eastern Sun: editions of 29th and 30th March 1970

- Singapore National Library and the National Archives of Singapore

- Special thanks to Eli Solomon, who gave access to files from his personal collection for the final composition of the text