The year 1997 was one of the most interesting, controversial and exciting in the history of Formula 1: in addition to 4 different teams achieving victories throughout the year (Williams, Ferrari, McLaren and Benetton), the battle between Michel Schumacher and Jacques Villeneuve polarized the dispute for the category title until the final race of the season – and the dramatic end, with the disqualification of the German in the last race of the year (which gave the title to the Canadian Villeneuve) was the climax of another memorable season in the history of Formula 1.

Amid all these exceptional and spectacular factors that surrounded the 97’ championship, one of them can certainly be highlighted: the promotion of the Luxembourg Grand Prix, on the mythical Nürburgring circuit. Carried out only due to a very specific combination of factors, which include the will of the track promoters and representatives of Formula One Management (FOM) and F.I.A. in keeping one of the most profitable races on the calendar, but without having the right to use the German GP banner (which for 97 belonged to Hockenheim), the Luxembourg GP became one of the exceptional cases in the history of F1: from a country that hosted a GP of the category outside its territorial borders.

Although the 1997 and 1998 editions (which also took place under the same regime) are the best known in the history of the Luxembourg GP, this would not be the first time that the Grand Duchy would host competitive single-seater races. The true story of the Luxembourg GP began more than 45 years earlier, with the likes of Stirling Moss, Peter Collins, Johnny Claes and John Cooper navigating through some of the country’s most treacherous streets.

Luxembourg GP: Origins

The context of the emergence of the Luxembourg Grand Prix is similar to that of several other races in the post-WW2 European environment: after years paralyzed by the conflict, all that the motorsport drivers at the time wanted was to compete in as many races as possible, wherever possible. Since there was no shortage of machines and people interested in participating in these events, promoters and organizers were quick to take advantage of the opportunity that existed at the time.

On the other side of the spectrum, governments and sports associations also believed in the potential of motorsport as a complete tool, within its economic and social plans: promoting races proved to be cheap to do, due to the few investments that (still) were needed in their organization. Furthermore, such events were a form of propaganda, painting an attractive portrait against a backdrop of desolation that followed the global conflict. Intertwined with this, motorsport became a cheap and accessible form of entertainment for the public, who were looking for leisure after the years of war deprivation.

Thus, events in the most traditional international automobile hubs, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, France and Belgium, soon returned to the international racing calendar. In addition to these, other peripheral countries, such as Austria, Czech Republic, Switzerland and Spain, also rejoined the agenda, contributing with some other traditional events.

Other countries, on the other hand, took advantage of this opportunity to definitively place themselves on the international map of high-performance motorsport: for example, Finland, which before the war already hosted GPs of a reasonable scale, but only after the conflict ceased began to be frequented more regularly by high caliber pilots. As another positive example, the Netherlands also deserves to be highlighted. Before WW2, the dutchman were in the shadows of the traditional events held in neighboring Belgium. But the end of the conflict presented the opportunity that the country was looking for to expose itself, and after that, the Low Countries would become one of the most traditional stops in world motor sport.

Seeing the (re)birth of motor sport in its closest neighbors and also contemplating the possibilities of such a choice for the future, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg also decided to participate in this wave of resurgence, seeking to promote its national Grand Prix for the first time. This would be the necessary exclamation that the small country needed to give in the European scenario at the time; Therefore, it is worth remembering that Luxembourg was one of the areas most affected by the Second World War, being one of the countries with the longest Nazi occupation (from May 1940 to February 1945), in addition to being the scene of several battles – especially the Battle of the Bulge, which transformed the small country into a large battlefield, destroying much of the civil infrastructure that existed in the Grand Duchy.

This would be practically a new experience for the Automobile Club du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (A.C.L.) as the association had previously hosted only 1 major event in its entire history: this was the Grand Prix du Centenaire, held in 1939 in honor of 100 years of the Grand Duchy’s independence. Open to Sports Cars and featuring drivers such as G. Farina, E. Villoresi, C. Biondetti and P. Lavegh, the race was won by the charismatic Jean-Pierre Wimille, aboard a Bugatti T57.

For 1949, Sports Cars would be brought back again, as a form of the A.C.L. continue to acquire the necessary experience so that, one day, it could finally bait the desired single seaters. The chosen location for the race would be the small village of Findel, 8 kilometers northeast of the center of Luxembourg City. The main reason for this choice was that the location was just a few meters away from the only reasonably sized airport in the country, which would greatly facilitate the flow of people and teams through the location.

Measuring exactly 3,764 meters, the Findel circuit was almost triangle-shaped, formed by what is today the Neudorf and Trèves streets, on the outskirts of the airport. The most technical points of the track were the sequence of zigzags on Rue de Neudorf, in addition to the sharp final curve of the track (which is in front of where the administrative buildings of Cargolux and Luxair are currently located). There was a small amplitude on the circuit, as the track was separated into the ascending (Trèves) and descending (Neudorf) sectors.

As was to be expected in any race in the 40s/50s, safety was a word almost ignored by everyone, and some other problems were immediately recognizable in the design of the Findel circuit. The first was the lack of visibility in critical parts of the track: in some places, the problem was the blinding sun; in others, it was trees; and at some points, it was both! The lack of separation between the public and the track was already common and accepted by all parties involved, but the trees on both sides of Rue de Neudorf meant that the margin for error was almost non-existent – if that wasn’t enough, the problems on the track surface in this section of the track were clearly visible, due to several undulations in the asphalt (this fact was reported by various media outlets at the time).

Despite this, on May 15, 1949, the I Grand Prix du Luxembourg was held, with the organizers managing to attract representatives from Belgium, France, England, Italy and Luxembourg, totaling 12 drivers. In the end, it was Ferrari who triumphed in the race, with Luigi Villoresi becoming the first champion of the Luxembourg GP, aboard a Ferrari 166 MM, entered by the Italian manufacturer itself.

The moderate success of the 1949 edition of the GP was enough for the Automobile Club du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg to become enthusiastic about the idea of promoting an international race for racing cars on an annual basis and, in 1950, the II Grand Prix du Luxembourg was contested (which coincidentally also had 12 drivers on its entry-list). This ended up being another race dominated by Ferrari, with the official Scuderia duo of Alberto Ascari and Luigi Villoresi taking the first two places in the race. And it was just by a minimal margin that the first three spots on the podium weren’t taken all by 166MMs, as for a matter of seconds, Herman Roosdorp, in a private-entry Ferrari, was beaten by Jacques Swaters for third place, in a Veritas.

Even though they did not attract the expected number of competitors, the 1949 and 1950 editions of the Luxembourg GP served the purpose of giving the A.C.L. the necessary know-how so that the institution could promote a larger-scale event in the near future. And, without waiting for any further delay, the organization decided to take the big step, finally replacing the Sports Car regulations with one for single-seaters. However, these would not be the much-coveted F1 or F. Libre cars; and yes, those of a new category, which had become a European sensation in the early 1950s: Formula 3.

500cc Formula 3: A Motorsport Revolution

Despite gaining widespread attention at the beginning of 1949, when races in Brussels, Zandvoort and Oslo became the first semi-official Formula 3 events on continental European soil, the history of the 500cc F3 actually had its origins 10 years earlier, in the country that would really popularize and spread this category: England. More specifically, the origins of the 500cc regulations would come from a small group of amateur drivers from the city of Bristol, in the period of uncertainty before WW2.

With a limited budget, what this group wanted was what almost every amateur driver looks for: a low-cost high-performance category, that did not require a large commitment of time and resources to have a competitive vehicle. The solution found to this dilemma was the combination of cheap and abundant chassis, like those of Austin Sevens and Fords of the Models T, A and B (all manufactured in the UK itself), with motorcycle engines, notably more economical than those that equipped the cars of the time.

The combination was to prove incredibly successful in the short time it could be applied, with global conflict putting a stop on this promising development. Luckily, a few years later, as the war was heading towards its final moments, the structure of the 500cc formula could finally be reactivated, and the creative process was reignited as quickly as it had been extinguished in 1939.

The 500cc F3 proposal seemed to be a flawless concept, and, obviously, it didn’t take long for it to start spreading across England. Well-known motorsport places in the British Isles, such as Shelsley Walsh and Prescott, were the first places outside Bristol to accept 500cc single-seaters on their entry-lists, as early as 1946. Names such as John Cooper, Eric Brandon and Frank Aikens were the ones who more marked this first phase of F3, which would last until the beginning of 1948.

At this time, a sequence of changes occurred, which would shape the category until practically the end of the 50s. The first was that the amateurism began to give way to tones of semi-professionalism in F3: the “poor man’s racing car”, as the 500cc F3 cars were known until then, would be replaced by increasingly refined machines, especially those created by the Cooper Car Company, founded in late 1947.

Dividing his duties between driver, team owner and car manufacturer, John Cooper hoped that 1948 would provide his newly launched brand with a great moment of prominence – and expectations were duly fulfilled. The manufacturer’s first official car, the Cooper MKII T5 (equipped with a 500cc J.A.P. engine), proved to be a revolutionary machine in the category, demonstrating a disproportionate level of superiority in the hands of several drivers. Built in just 12 units, the MK.II T5 was the starting point for several British pilots in pursuit of their dream of becoming world-class pilots; the main exponents being Stirling Moss and Peter Collins.

Another important step was the rupture in the hierarchy that managed the 500cc Formula 3 until now. Til the middle of 1948, much of the structure of the category’s races was based on the regulations stipulated by The Bristol Airplane Company Motor Sports Club (BACMSC), birthplace of the 500cc F3, and which had the function of organizing and framing the category within the British national calendar. However, it wasn’t long before the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC) began to enter the F3 scene, claiming the need to sanction (on a more regular basis) 500cc F3 events. And, until early 1949, almost all British national-level events were sanctioned by BARC, with the support of local clubs.

1950 marked the definitive consolidation of Formula 3 in several aspects: Cooper had demonstrated itself to be the most competent manufacturer in the category, with the old MK.II model now being joined by the more modern MK.III and MK.IV (equipped with either a J.A.P. engine or a Norton engine), which proved to be almost unbeatable in the category. This did not stop other automakers from trying their luck in the category, such as Emeryson, Turner-Kieft and J.B.S. (which also offered J.A.P. or Norton engines as options).

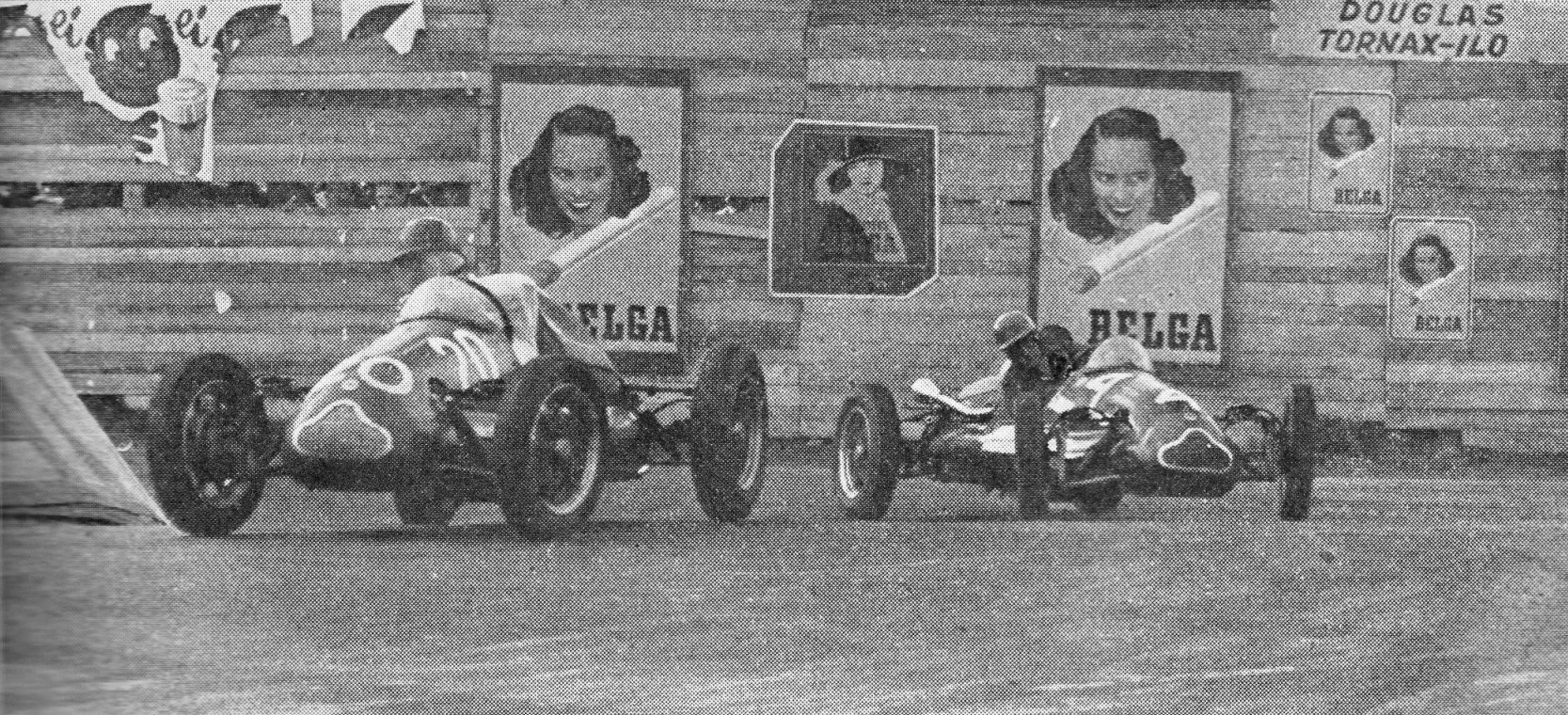

Another point that demonstrates the solidification of F3 was the definitive expansion across Europe, with British drivers having their first real contact with their counterparts on the other side of the English Channel. The Coopers, Kiefts and Emerysons were soon joined by the French D.B.s, which proved to be the best continental cars in F3, equipped with 35HP Panhard engines.

Other countries also had their representatives in the category, such as Germany, whose main exponents were cars manufactured by Monopoletta (equipped with BMW engines) and Scampolo (carrying DKW machinery). Italy, as always represented in any automotive environment, also participated in F3, with the highlight being the Giaur ‘500’ F3 Sport, which fitted an engine derived from the FIAT Topolino. Netherlands, with their aluminum bodied Beels/J.A.P.s, was also a country that commonly appeared in the entry-lists of European F3 races.

The acceptance by the F.I.A., at the beginning of 1950, that the 500cc regulation could be used as a standard Formula for several countries, was the final detail that Formula 3 needed to carry out its final expansion across Europe. The recognition of the highest motorsport entity finally gave a tone of legitimacy to the various races contested on this formula, which now reached several locations that were previously unimaginable for a single-seater category.

Therefore, it was from 1951 onwards that the 500cc F3 entered its boom period, which would last until 1960. Cooper was the first to unveil its model for the now ‘official’ Formula 3, which, it hoped, would continue with the absolute dominance that the manufacturer had managed to maintain since mid-1948. The Cooper MK.V (T15) redesigned a good part of the lines that, until now, marked the lineage of the F3 Coopers. More streamlined and aerodynamic, the big new feature of the car was the possibility of removing the fairing that protected the engine without great effort, allowing quick repairs to be made in a normal racing situation.

Equipped with reliable J.A.P. or Norton engines, these models have become the most coveted vehicles in the category; but, unlike the MK.II, .III and .IV, which were widely sold on the market to privateers, the MK.V models were almost exclusively used by teams linked to the construction company itself. The Cooper Racing Team represented the official effort of the Cooper Car Company, and featured some of the best British semi-professional drivers of the time. On the other hand, Ecurie Richmond was considered a Cooper satellite team, and therefore had also managed to acquire the MK.Vs for the 1951 season.

James Bottoms and Sons, known simply as J.B.S., also presented its model updated to 1951 specifications, with a complete overhaul of the front suspension system and chassis rigidity. Instead of Cooper, which placed its bets on two teams truly prepared to win victories, J.B.S. bet on the strength of smaller teams and privateers, who would flood the grids with cars built by the manufacturer. For example, at some race or other (particularly in England, Belgium or Holland) it was not uncommon to see a parity between Coopers and J.B.S.s.

Another company that did not want to be left behind in this race for technological development was Turner-Kieft, which, after the moderate success of the MK.I model, was looking for inspiration for its newest project. It was found in a young and ambitious Stirling Moss, who was looking for a new F3 machine after his days driving Coopers. The final result of the partnership between Kieft-Moss was the CK 51, which solved several problems present in the first model produced by the Wolverhampton manufacturer.

The weight distribution problems were almost all resolved, with a new suspension set, which made the car much more balanced and responsive in racing situations. Another novelty that helped considerably to solve this problem was the new layout of the vehicle, with the cockpit being placed well in front of the machine’s center of gravity and considerably balancing the weight inequality between the engine and the pilot. This solution was also mainly responsible for giving the CK 51 its most striking feature, which was its teardrop-shaped bodywork and very low-profile.

Despite being the most modern car on the grid, few orders reached the company, which meant that the majority of cars were entered by the constructor’s own team, Kieft Racing Cars. One reason for the little interest from third parties in Kieft cars was that, despite being more refined (aerodynamically speaking) than their competitors, they presented a more disadvantageous cost-benefit ratio compared to the J.B.S. and Coopers.

For example, in 1951, a Kieft CK 51 could be ordered for £782, fully equipped with a J.A.P. engine and Norton gearbox. On the other hand, a J.B.S., also fully equipped, could be purchased for around £600; and a Cooper MK.V, also ready for racing, could be purchased outright for £582. The values are even lower if one takes into account that most transactions at the time for F3 cars involved second-hand cars, much cheaper than the ‘machines of the year’.

Another factor that also compromised the Kieft’s greatest sales success was the sequence of delays that surrounded the project. Originally scheduled to enter operational status at the beginning of 1951, the first CK 51 only participated in an official race in mid-May. This meant that Moss, who had been quite committed to the project, would have to settle for an MK.I when he embarked on his Luxembourg adventure.

1951: The First Luxembourg GP For Single Seaters

With the exception of support events for the renowned Pau GP, the Luxembourg GP would basically be the kickoff of the F3 seasons across continental Europe, given that only in England had activity in the category resumed after the interseason. On the island, activity had been frenetic since early March, when the first regional B.A.R.C. races for Formula 3s were held.

However, F3 officially began in England in 1951 with the Earl of March Trophy, held at Goodwood and won by Alf Bottoms, in a J.B.S./J.A.P – a victory that served mainly to demonstrate that Cooper would finally have a worthy opponent in the year that just had begun. Afterwards, other stages of reasonable size took place in Castle Combe and Brands Hatch, with J.B.S., Cooper and Kieft constantly taking turns at the top of the podium in these events. However, at the beginning of May, the time had come for the cream of British drivers to head towards little Luxembourg, in what would be the first international meeting recognized by the F.I.A. for Formula 3.

More than 25 entries were received by the A.C.L., with English pilots joining representatives of Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Italy and Luxembourg itself. Despite this plurality, it was undeniable that the British had the absolute upper hand on this face-off, whether in terms of team structuring or in other more subjective and interpretative aspects.

The British legion was captained by Cooper, which deployed its two ‘teams’ for the event in Luxembourg: the Cooper Racing Team had sent three representatives, all of them equipped with the recently introduced Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V: John Cooper himself would lead the trio of drivers, accompanied by the experienced Ken Carter (British national F3 champion in 1950) and the young promise Bill Whitehouse.

Ecurie Richmond, founded at the end of March 1951, had also managed to send a delegation to continental Europe: Alan Brown and Eric Brandon would also drive the new Cooper MK.V; but these, unlike the factory team vehicles, were equipped with Norton engines, which performed almost equally to the J.A.P. In any case, Ecurie Richmond was an attraction in itself, because despite appearing to be an almost professional team by F3 standards, it was nothing more than a private (and wild) venture, founded in partnership by Alan, Eric and Jimmy Richmond. However, this did not stop Ecurie Richmond from quickly standing out in the competitive F3 scene.

Kieft Racing Cars has selected two of its most promising drivers for the race: the aforementioned Stirling Moss would be joined by Ian Burgess (who would become best known for his appearances in F1 for Scuderia Centro Sud, at the end of the 1950s). Because of unexpected problems that delayed the final development of the CK 51, both Moss and Burgess would have to do the best they could with Kiefts MK Is, equipped with Norton engines.

The last representative of the major English car manufacturers was the J.B.S. Team, which would have just one driver as its representative: the son of James Bottoms (owner of J.B.S.), Alf Bottoms. The pilot would have at his disposal his father’s newest creation, a lighter and more powerful version of the J.B.S. ‘500’, which was derived from another 500cc F3, the Cowlan 500. Alf had already demonstrated the car’s potential in the first British F3 races of 1951, and he hoped that an international success could be excellent for his father’s firm’s business.

In addition to these, other English representatives submitted their entries, mainly as privateers: Don Parker, one of the most successful F3 drivers to date, had registered a brand-new J.B.S./J.A.P., which replaced his venerable Parker Special, which had almost 2 years of continuous services in its back. Two other pilots were also equipped with James Bottoms and Sons vehicles: Ron Dryden, who had an older model of the J.B.S. equipped with a Norton engine, and Frank ‘Winco’ Aikens, a former RAF bomber pilot, who would pilot a J.B.S. equipped with a rare Triumph Speed Twin engine.

As always, British privateer Coopers also showed up in reasonable numbers for the race, representing a wide gamma of vehicle variants in Luxembourg: Alan Rippon would drive an old MK.III/J.A.P.; Austen May and Ray Merrick each piloted a MK.IV/J.A.P.; Meanwhile, Sir Francis Samuelson would have at his disposal one of the few MK.Vs sold to third parties – and also equipped with a J.A.P. engine. And, closing the English entries, the only Emeryson in the race, driven by Ted Frost (equipped with a Norton engine).

In response to this British invasion, the main European countries involved in Formula 3 mobilized the best they had within their borders: three D.B./Panhard ‘500’s were sent from France, to be driven by Michel Aunaud, Francis Liagre and Fernand Chaussat. Representing Deutsch & Bonnet itself, these cars were certainly the ones that would pose the most danger to the British elements on the grid; From Italy, two cars also came, the GIAURs from Squadra Taraschi, driven by Bernardo Taraschi (the famous Italian car designer) and Filipo Hercolani.

However, the majority of European representatives would come from West Germany, where a strong movement in favor of F3 had been developing since 1948. Both Scampolo and Monopoletta sent 2 representatives each, totaling 4 entries of an entirely Germanic nature. The Scampolo cars would be driven by Hellmut Deutz (in a version equipped with a DKW engine) and Walter Komossa (this one equipped with a BMW engine), while the Monopolettas (all equipped with BMWs) would be driven by Karl Schermer and Walter Schlüter.

Both Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg would have one representative each in the race: from the first came the registration of the well-known and experienced Belgian driver Johnny Claes, who gave a positive nod to compete in the race with a Cooper MK.IV/J.A.P., and which would run under the auspices of the driver’s private team, the Ecurie Belge. Representing the Netherlands was Ecurie Internationale, owned by the Chief Executive of Goodyear in Belgium, George Buijtendijk. Once again, the team owner also played the role of driver, with Buijtendijk having a Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV at his disposal.

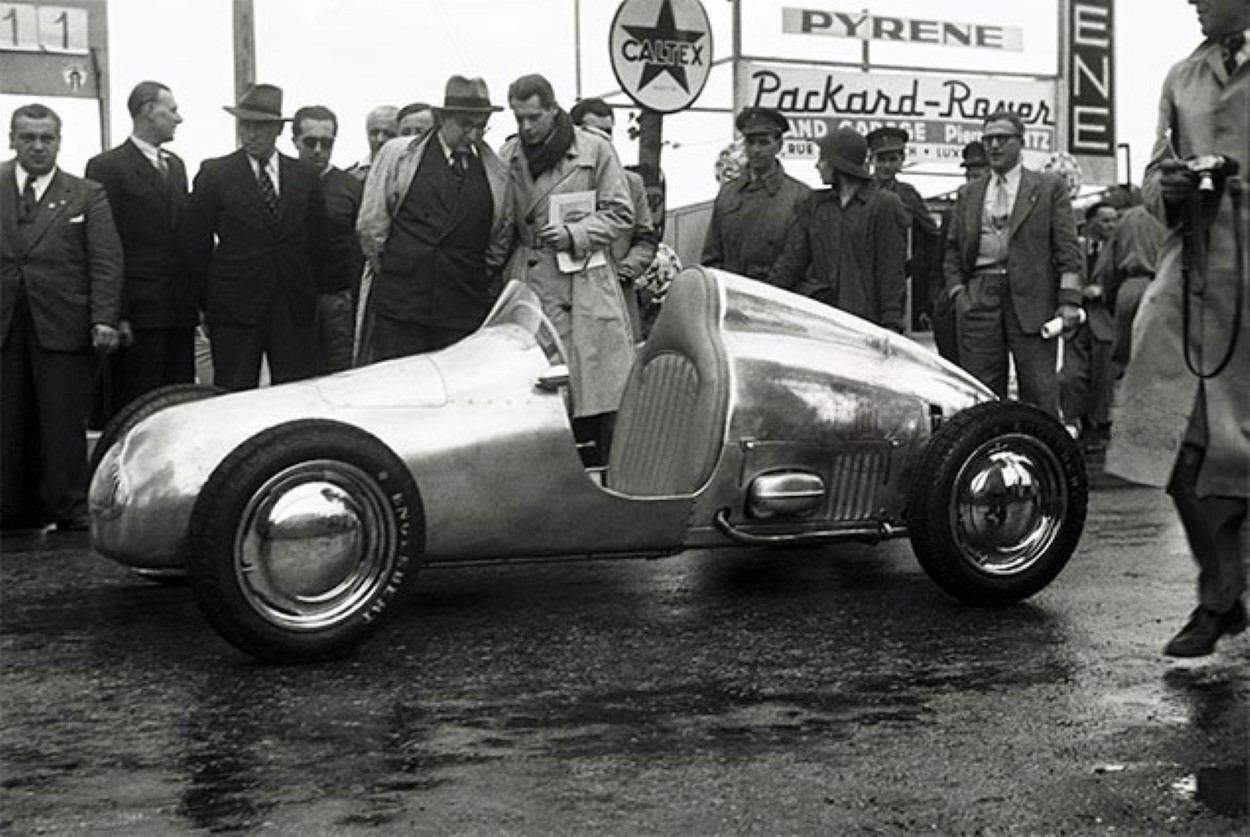

The most unique case, however, was that presented by the registration coming from the country hosting the event itself. Since 1949, a project had been underway in Luxembourg to build a national competition vehicle, headed by the great name of motorsport in that country: Jos Zigrand. Zigrand was a well-known racing driver in the region between Germany, France and Belgium, and, in addition to being a pilot, he worked in parallel as an official representative of Bugatti in Luxembourg.

Having as his great ambition the creation of a product that truly represented his country on the track, Zigrand set to work on creating the first vehicle designed in Luxembourg – and, using all the contacts he had made over the years in his automotive career, the pilot managed to complete this task just in time to present the machine, called ZIG, at the 1950 edition of the Luxembourg GP.

At first glance, the car looked like an indigenous copy of a Cooper MK.II, with the car lines closely resembling the British machine. However, some details clearly stood-out in the design, especially due to the limitations imposed by the machine’s birthplace: for example, due to the scarcity of aluminum and other essential materials for the construction of the vehicle in Luxembourg (still a reflection of WW2), many of the components used in the construction of the ZIG were reused from other secondary sources: for example, the car’s bodywork was built with aluminum panels reused from Second World War planes, while the gauges were borrowed from other existing vehicles.

The initial rustic appearance of the vehicle was slowly refined throughout 1950, until the car was finally ready for its debut, in 1951. To this end, Jos Zigrand had built a second prototype, which would be the vehicle that would represent the Grand Duchy in its national GP. Unlike the ZIG (1), the ZIG (2) had more subtle lines, in addition to more important mechanical modifications – the main one was the replacement of the BMW engine, which had proven insufficient in tests, with a brand new J.A.P., much more powerful and reliable.

For personal reasons, Zigrand could not drive the vehicle in the race, and Paul Ries, the greatest promise in Luxembourg motorsport at the time, was assigned to his place. Even so, Zigrand participated in another important step towards making his dream come true: the formation, around the ZIG, of the Ecurie Luxembourg – which would in fact become the first Luxembourgeoise team to participate in an international Formulas race.

1951: The Race

The Luxembourg GP traditionally took place on Himmelfahrtstag (Ascension Day) which, in 1951, fell on May 3rd. Due to this peculiar date, many of the British drivers who would take part in the race in the Grand Duchy preferred to skip one of the smaller stages of the British F3 national championship (in Gosport – which would take place on April 29th), preferring to avoid any setbacks that might occur. could hinder their arrival in Luxembourg. Because of this, a peculiar picture was formed, with most of the pilots being present at the site even before the start of the sporting activities.

However, due to the location of the circuit, which was on the only access route to or from the Findel airfield (as already mentioned, the only large airport in Luxembourg), it took a while for pilots could be released to carry out their first track activities (which practically only started to happen on May 2nd).

As soon as the cars completed the first laps around the 3764-meter-long circuit, one thing became pretty clear: all the continental cars were off the pace set by the Coopers and J.B.S.s, which were traveling much more swiftly and naturally around the track. The Monopolettas, Scampolos and Giaurs suffered on the way up Trèves Street, in addition to being much slower in terms of final speed. The D.B.s performed a little better, with Aunaud being the main highlight of the French team.

Even so, all this effort was insignificant compared to the ease with which the Coopers dominated the curves of the Findel circuit. The Cooper Racing Team and Ecurie Richmond demonstrated superiority in the new Cooper Mk V, while the older Mk IV and Mk III also followed suit with their younger counterparts. But the big surprise was the J.B.S., which, until the moment of free practice, were the fastest cars on the track.

Much of this performance was due to Alf Bottoms, who led almost every timed session before the race. However, a disaster would put an end to what looked like it would be a brilliant weekend for the driver. In one of the training sessions on Wednesday, Bottoms would suffer a fatal accident aboard the J.B.S., almost completely destroying the machine in the impact.

According to what was reported at the time, the accident happened on the final curve of the track, the harpin that connected Neudorf and Trèves streets. Instead of the driver slowing down to make this tight turn, the car was seen accelerating more and more, with Bottoms desperately trying to stop his machine. As a desperate measure, the Brit tried to throw the J.B.S. to the outside part of the track, with the aim that the vehicle decelerates naturally rather than mechanically.

The problem is that the pilot did not expect a civilian car to be parked at the scene and it was too late to avoid the collision. J.B.S. entered under the parked car and Bottoms died instantly on impact. In subsequent investigation, the theory was accepted that the entire accident was due to one of Alf’s shoes, which probably got stuck in the vehicle’s accelerator while he was trying to brake the machine.

The shock was immediate, with the news of the driver’s death reaching the paddocks almost immediately. The location of the accident, at most a dozen meters from the pit area, was one of the factors that caused this information to reach this area quickly – the other was that the crash occurred almost next to the main grandstand of the circuit. , an element that allowed a hundred spectators to witness the last moments of the promising Alf Bottoms.

Even with this fatality, the Luxembourg GP events would not be suspended according to the A.C.L., with the schedule being maintained according to schedule. The activities of Day 2 subsequently continued smoothly, with Don Parker and Ron Dryden assuming the roles of J.B.S.’s main representatives. for the next day’s races.

The long-awaited May 3rd had finally arrived, bringing with it the long-awaited first GP for single-seaters in the Grand Duchy. To compete in the race, the almost 25 cars present would be divided into 2 groups, with each competing in a 12-lap elimination heat. The best classified in each heat would have the chance to compete in the final race, 25 laps, which would crown the Luxembourg Grand Prix champion.

For the first heat, the following drivers were selected (alphabetical order): Alan Brown (Cooper/Norton MK.V); Alan Rippon (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.III); Fernand Chaussat (D.B./Panhard ‘500’); Francis Liagre (D.B./Panhard ‘500’); Francis Samuelson (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V); John Cooper (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V); Johnny Claes (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Karl Schermer (Monopoletta/BMW); Paul Ries (ZIG/J.A.P.); Ray Merrick (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Ron Dryden (J.B.S./J.A.P.); Ted Frost (Emeryson/Norton) and Walter Komossa (Scampolo-BMW).

The start signal was given and the 13 vehicles raced down the main straight of the Findel circuit. Alan Brown took the lead, followed by Ron Dryden. John Cooper and Ray Merrick were close behind, pulling the rest of the pack. Despite lightly touching the back of Johnny Claes car at the start, Karl Schermer had so far achieved a spectacular start, leaving the last positions on the grid and positioning himself in fifth place at the end of the first lap.

Start of the second lap and Dryden was leading! Next came Cooper, Merrick and Schermer. So where was Alan Brown? The pilot had made a gross error, missing the entrance to one of the curves in the central part of the track. The result was that the driver lost the lead and precious seconds in the race, losing several positions as he tried to return to the track.

Ted Frost and Johnny Claes were engaged in an interesting duel for the now fifth position, with the Emeryson driver doing better until the fourth lap, when he was forced to withdraw from the race due to mechanical problems. Another who was also affected by problems was Karl Schermer, who gradually lost positions to his main rivals.

While some had their problems, others seemed to be recovering from them: Alan Brown started an impressive recovery from the 3rd lap, and, after being among the last positions on the grid, the driver was already within the top-3 at the 6 o’clock mark. laps completed. A sequence of quick overtakes on slower cars, such as the D.B., Scampolo and ZIG, was essential so that the driver did not lose too much time and contact with the race leaders.

Speaking of the Luxembourg car, Paul Ries performed a modest test in the first real ZIG/J.A.P. test: the driver had difficulty keeping the car at the same pace as his strongest rivals, and it didn’t take long for Ries to be one lap behind the rest. of the platoon. Not wanting to take any big risks, Paul was content to finish the race, counting on other drivers abandoning themselves so that ZIG could climb as high as possible on the race’s classification table (in the end, Ries would finish the heat ranked in 8th position).

Returning to the leaders, halfway through the race, the order was: Ron Dryden leading, a couple seconds ahead of John Cooper; giving the chase (albeit already very distant) a trio had formed, composed of Alan Brown, Ray Merrick and Johnny Claes. A dozen seconds separated them from the only other drivers still around the leader lap: Alan Rippon and Sir Francis Samuelson. However, this formation did not last long, as in an attempt to overtake Merrick in the final corner of the lap, Claes lost control of his car and stopped only in the small escape area of the place. The Belgian quickly tried to get back on track, but a broken oil pipe sealed the end of the race for Claes.

The rest of the race went without problems and major changes, with Ron Dryden completing the 12 laps in 23m3s, 3 seconds ahead of second place John Cooper. Alan Brown was almost 30 seconds behind, achieving a surprising third place, after an excellent recovery race.

A few minutes break was given so that the drivers from the second heat could line up on the grid. At the fall of the checkered flag, 13 drivers were in their respective starting positions: Austen May (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Bernardo Taraschi (Giaur/FIAT); Bill Whitehouse (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V); Don Parker (J.B.S./J.A.P.); Eric Brandon (Cooper/Norton MK.V); Frank Aikens (J.B.S./Triumph); Filipo Hercolani (Giaur/FIAT); George Buijtendijk (Cooper/J.A.P. Mk.IV); Helmut Deutz (Scampolo/DKW); Ken Carter (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V); Michel Aunaud (D.B./Panhard ‘500’); Stirling Moss (Kieft/Norton MK1); and Walter Schlüter (Monopoletta/BMW).

Once again it was an Ecurie Richmond Cooper who took the first spot at the start of the race, with Eric Brandon taking the lead ahead of Don Parker and Bill Whitehouse. However, what happened was just a repetition of the events of the first heat: this lead was short-lived, with a J.B.S. quickly contesting this lead, to take it before the start of the second round. However, unlike his teammate, Brandon lost his position only due to the merits of Don Parker, who managed to execute a perfect overtaking maneuver right after the harpin.

So, at the beginning of the second round it was Parker’s J.B.S. leading the pack, followed by Brandon and Whitehouse’s Coopers. Ken Carter was also in hot pursuit of the leaders, while the other drivers were already a little behind. Because of this, the main attraction of this heat was the clashes for intermediate positions, which continued almost until the end of the race.

Walter Schlüter and Helmut Deutz were engaged in an all-German duel at the end of the field, while the Giaurs competed for the worthless last position in the race. Further ahead, Stirling Moss tried to take his Kieft along with Austen May, Michel Aunaud and Frank Aikens, but the Brit ended up overdoing his efforts and ended up breaking his machine in less than 5 laps.

Speaking of the trio of May, Aunaud and Aikens, they were obviously the ones who offered the best show in this heat: three cars from three different brands constantly alternated between 5th, 6th and 7th positions, with each driver making the most of the advantages of their car: May (Cooper) certainly had the most balanced car of the trio, while Aikens (J.B.S.) had the vehicle with the best acceleration and Aunaud (D.B.) the fastest in a straight line.

As this battle unfolded, Don Parker looked increasingly comfortable in the lead, while Eric Brandon and Bill Whitehouse cooled their nerves, knowing that their current positions would be enough to qualify them for the final race. However, Ken Carter was not satisfied with being outside the top-3, and, in an effort to try and catch up to his rivals, he damaged his gearbox, completely compromising his performance in the final laps of the race. By the end of the twelve laps, his 4th place had become a 7th!

This was the last major change to affect the front pack of the race, with Don Parker crossing the finish line at cruising pace, 13 seconds ahead of Eric Brandon. Bill Whitehouse (3rd), Austen May (4th) and Frank Aikens (5th) completed the ranking of the five best classified drivers in the heat.

Another break was necessary, so that the times could be recorded and which vehicles would be classified for the final race. The work of forming the grid for the final race by the A.C.L. lasted a few minutes longer than expected, due to some drivers who qualified for the final stating that their vehicles could not withstand another 25 laps. A few small adjustments, and everything was ready to compete in the final race in the Grand Duchy.

Of the 14 cars classified for the final race, only 12 lined up on the grid, which was formed like this (first three rows): – in the first, with three cars Ron Dryden (inner side), John Cooper (middle) and Don Parker (outer side ) – second row: Alan Brown – third: Michel Aunaud (inside), Ray Merrick (middle) and Frank Aikens (outside). The 2 pilots who retired minutes before the start were Eric Brandon (flywheel trouble) and Bill Whitehouse (broken cyclist head stud).

With everyone in their positions, the starting signal was finally given. Alan Brown was the fastest at the start, and, overtaking all the drivers on the front row, took the lead, followed by Ron Dryden. Don Parker had problems when, in his desire to start as hard as possible, he stalled his J.A.P engine. However, this was just a small setback, and within a few moments, the pilot was back in the race (albeit in last place!).

Another one who had problems was John Cooper. After a good start, which placed him in third behind Brown and Dryden, John was excited by the momentum and, right in the first corner, he missed the braking point and collided with one of the strawbarriers on the outside of it. Despite the scare, John managed to return to the race; However, the damage could have been much greater: the driver and team owner Cooper narrowly escaped being beheaded, due to a low-lying deer in the area.

Crossing the finish line for the first of the 25 laps valid for the GP, it was Alan Brown who was leading, with Ron Dryden just tenths of a second behind. In third position, Don Parker was already reestablished, who had made a storming recovery lap, overtaking more than 7 cars in less than 3.5km – an impressive feat for any category in world sport.

Therefore, the order of drivers was as follows at the start of the second lap: 1st Alan Brown, 2nd Ron Dryden, 3rd Don Parker, 4th Ray Merrick, 5th Ken Carter, 6th Francis Samuelson, 7th Michel Aunaud, 8th Alan Rippon, 9th George Buijtendijk, 10th Frank Aikens, 11th Helmut Deutz, and 12th John Cooper.

Third lap and changes in classification: an unexpected stop in the pits by Michel Aunaud caused the Frenchman to lose a few seconds in the dispute – all due to a leak in the car’s fuel tank, which forced the team to carry out an emergency repair on the vehicle. On the next lap, the big surprise was Ron Dryden, who managed to overtake Brown for the race lead. Another who also managed to move up in the general classification on this lap was Ken Carter, who took fourth place, which previously belonged to Merrick.

Even with the stop in the pits, Aunaud was another one of the drivers who had made a spectacular lap, to regain practically the same position he was in before the stop. In less than a lap, the driver had already progressed to 6th position, now fighting a beautiful duel with Ray Merrick and Alan Rippon.

The battle for the lead, however, was what attracted the public’s attention: Alan Brown had managed to retake the lead on the sixth lap and, on the seventh, Brown and Dryden even collided. Don Parker could have capitalized on this opportunity, but the J.B.S. pilot had forced his machine excessively during his attack on the first lap and, at the beginning of the eighth lap, the driver retired from the race, due to a broken engine valve. A few moments later it was also Dryden’s turn to say goodbye to the contest, due to the engine chain coming loose, damaging the J.B.S. machinery beyond repair.

This left Alan Brown with a ‘comfortable’ advantage of a few seconds over Ken Carter, who, despite the damaged gearbox (which had not been changed in the interval between the qualifying heat and the race), continued to put pressure on the race. Further back, the dispute for third position intensified, with Merrick, Rippon, Cooper, Samuelson and Buijtendijk fighting bravely for the last position on the podium. The first to fall out of this dispute was Ray Merrick who, on the 13th lap, had gearbox problems. This exit promoted John Cooper to third position, after an overtaking that the driver had managed to execute on Rippon on the previous lap.

While these events were unfolding, a dramatic episode was defining the leadership dispute. Seeing the fuel gauge dip dramatically in the last few laps, Alan Brown became suspicious of a leak in his vehicle’s tank; and, doing the math, the pilot knew that with the amount of fuel still left in the tanks, there was little hope of finishing the race.

So, on the 14th lap, the driver decided to stop at the Ecurie Richmond pits to quickly refuel. Having a 6 second lead over Carter at the pit entrance, Brown was now 12 seconds behind the Cooper works driver at the exit! Something that would break the spirit of any driver, but would never dampen his desire for victory – because of this, as soon as he returned to the track, Brown began chasing the now leader Ken Carter.

Despite substantially reducing the gap in the following laps, it would be very difficult for Brown to regain the lead relying only on himself. Then, luck smiled on the driver on the 18th lap: carrying out the zig-zag session along Rue de Neudorf, Carter felt his car shake and then die. He was another victim of engine problems, due to one of the chains coming loose.

This promoted Alan Brown to the lead again – one he would not lose until the finish line. Further back, an almost safe second place for John Cooper became mere dust after a steering system problem forced John’s retirement on the 19th lap. Due to the problems of several drivers ahead, those who would end up inheriting 2nd and 3rd positions in the race would be Alan Rippon and Francis Samuelson, who were duly rewarded for their solid and error-free performances.

Alan Brown would take the checkered flag after 50m22s of racing, leading the Cooper MK.V to its first international success. On the other hand, with a time of 51m28s, and in the second highest place on the podium, Alan Rippon demonstrated that the old MK.IIIs could be hard work, if still driven well. But the greatest achievement of this race was undoubtedly that of Sir Francis Samuelson: it is worth remembering that at the time, the driver was 61 years old – therefore, a third place in a race full of young talents was something spectacular in itself.

In a subsequent final deliberation, the Automobile Club du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg considered the race a great success, even surpassing previous editions held for Sports Cars. Despite the great disappointment generated by the continental cars, especially the Giaurs, Monopolettas and Scampolos, which proved to be uncompetitive when placed head-to-head with their British rivals, the A.C.L. he was extremely pleased with the attention that the race had attracted, both on the national scene, but, mainly, on the international scene (which was the main objective of the A.C.L.).

Because of this, as soon as the 1951 Luxembourg GP ended, the general outlines of the 1952 event began to be drawn up – which was expected to be the definitive step towards the consolidation of Luxembourg motorsport.

1952: A New Year and New Challenges

A year went by before the charismatic Formula 3 cars returned to the Grand Duchy; and, the category’s scenario was reasonably different from that of 1951. In particular, the rise of some brands and drivers, while others began to slowly enter the category’s history pages.

Certainly, the most important factor that differentiated the 1951 and 1952 seasons was the supremacy of Norton engines on the grids, clearly overcoming the J.A.P. which, until then, had been the powerplant chosen by most top teams. This was due to the improvement in the performance curve of the Norton engines, which, in their most recent versions, surpassed the hitherto dominant J.A.P.s in all aspects (weight, gross power, acceleration).

This meant that many drivers who already had Coopers, J.B.S. and Kiefts competed for these engines, which were not yet widely available on the market. While the larger teams (such as Ecurie Richmond, the Cooper Racing Team and Kieft Racing) could order these engines directly from Norton, many of the privateers resorted to more primitive methods: such as buying new Norton bikes (especially the Dominators) just because of the Manx engines, which were transplanted directly to the F3 chassis.

It is worth remembering that, at this time, there were three versions of Norton engines available on the market: the first involved the Norton-Manx ‘single-knocker’, based on engines produced by Norton between 1937 and 1949. The second option was the so-called Norton-Manx ‘double-knocker’ (1950/51), due to the introduction of the double overhead camshaft, which replaced the old single-cam model. The third involved what was called the Norton-Featherbed (after the Featherbed-style motorcycles produced by the automaker), which were Norton-Manx engines produced from 1951 onwards and which introduced a system of sodium-filled exhaust valves.

In the sporting sphere, 1952 still felt the effects of the electrifying English national F3 season (the most important in Europe at the time). Ecurie Richmond shook the championship and surprised critics, managing to overcome competition from the factory-backed Coopers and Kiefts, achieving its first national title with Eric Brandon. Alan Brown, in the team’s second car, also did well, placing second overall in the points table. A fantastic feat for a team made up of just 5 people (Jimmy Richmond himself, Brown, Brandon and two mechanics: Michael “Ginger” Devlin and Freddie Sirkett).

However, Brandon’s achievement was not so easy, with the driver constantly being challenged by other cars similar to his, but also from J.B.S. (in the first half of the season) and Kieft (second half). This facet of the English season also demonstrated a shift in the balance of power in the category, which would become clear when the 1952 season began.

Especially affected in this process was J.B.S., which had a promising evolution slowed down by several problems within the tracks, which greatly affected the company’s development. Alf’s fatal accident at the 1951 Luxembourg GP would only be the first blow for James Bottoms that year: a few months after the accident in the F3 race, another of Bottoms’ sons, Charlie, died in a motorcycling race. The misfortunes continued, with Charles (James’ brother) narrowly escaping death in an accident during an F3 contest at Brands Hatch. And, if that wasn’t enough, Ron Dryden, who had become the team’s official representative after Alf and Charles’ accidents, was also the victim of a fatal accident, in the final race of the 1951 British F3 championship, at Castle Combe.

The problems with J.B.S. allowed Kieft to assume the undisputed position of second power in F3, behind Cooper. The manufacturer began its rise just over 10 days after the race in Luxembourg, during the prestigious International Trophy at Goodwood: Stirling Moss, now equipped with the interim CK51/52, had a spectacular race, winning the event by an advantage of more than twenty seconds and demonstrating the potential that the new machine had.

Due to this and other successes achieved throughout the year, Kieft launched the CK52 model in 1952, the company’s definitive machine. The vehicle was (at least superficially) almost an exact copy of the CK51, but incorporating some modifications that only existed until then in Moss’ model 51, the prototype used as a testbed for the team’s new technologies. Although officially listed as only having de J.A.P. motorization option for order, it was easier to find a Kieft CK51 or CK52 equipped with a Norton engine than with a J.A.P.. Well, it was quite simple to see why: Moss’ car, the company’s most successful to date, was specially fitted with a Norton “Double-Knocker” – and this success created an urge for Kiefts equipped with Nortons.

Meanwhile, at Subiton, Cooper was also preparing for the new season, publicly demonstrating its new vehicle at the end of 1951. The Cooper MK.VI might look aesthetically the same as the MK.V, but beneath the bodywork, one could spot huge differences between the two cars. The ladder structure, which until then had been the trademark of Cooper cars, was replaced by a tubular one, more modern and much more effective than the old construction methods.

In addition, other significant changes, such as a complete overhaul of the suspension system, the use of magnesium to replace other heavier alloys (which reduced the car’s weight by more than 30kg) and the reduction in the frontal area of the MK.VI compared to to the previous models, helped once again to make Cooper one of the top-rated brands in the dispute for the national F3 championships in 1952.

A new player had entered the fray for 1952, and its name was Saxon. Formed from a partnership between investor and motorsport enthusiast Mac McGee, and engineer Gordon Bedson, the company launched its first F3, the Mackson, in the first months of 1952. Designed completely by Bedson (who had extensive experience in the designing high-performance machines – for example, he was one of draftsmen involved in the development of the Valiant strategic bomber), the Mackson was a low-profile and extremely aerodynamic car.

Equipped with a Norton-Manx “double-knocker”, the Mackson was born with great expectations of becoming a more affordable alternative to the increasingly expensive and refined Coopers and Kiefts. However, the machine’s slow production rate meant that for the race in Luxembourg, only two Macksons were in racing condition.

1952: The Race

Unlike 1951, when the Luxembourg GP marked the beginning of the European Formula 3 season, in 1952 the race would be the second ‘stage’ of the European championship – 11 days before the race in the grand duchy, an event had been held in Brussels, attracting the big names in F3 at the time (and, in particular, the well-known English contingent of cars and teams).

Because of this race, the person who arrived with great expectations for the 1952 Luxembourg GP was Ken Carter, the only representative of the official Cooper team in the race – although Ken was technically registered as a privateer for this race. Ken Carter had managed to collect a spectacular victory in the Brussels race, having to use an old Cooper MK.V against the new vehicles lined up by Ecurie Richmond and Kieft. Despite this clear disadvantage, the driver’s skill was a decisive element in this race, which saw the majority of his rivals (with better vehicles) have mechanical problems or get involved in accidents.

Ecurie Richmond had once again made it clear that it would be present in Luxembourg, hoping to rekindle the spark that had propelled the team to the British F3 national championship in 1951. Since the end of the year, the team’s best results were only two second places (at the Brussels F3 GP and the Goodwood Earl of March Trophy), both achieved by Alan Brown.

Despite this, the duo formed by Brown and Brandon continued to be one of the most dangerous on the grid, even more so due to the closer relationship that the team had managed to establish with Cooper Cars, after the successful year of 51’ – one of the first consequences of this success was that the team was the first privateer to test and receive the new MK.VI, for example. Ecurie Richmond’s ties also grew closer with Norton Motorcycles, which allowed easier access to people like Steve Lancefield and Francis Beart, the most renowned (and sought after) tuners of Norton 500cc engines.

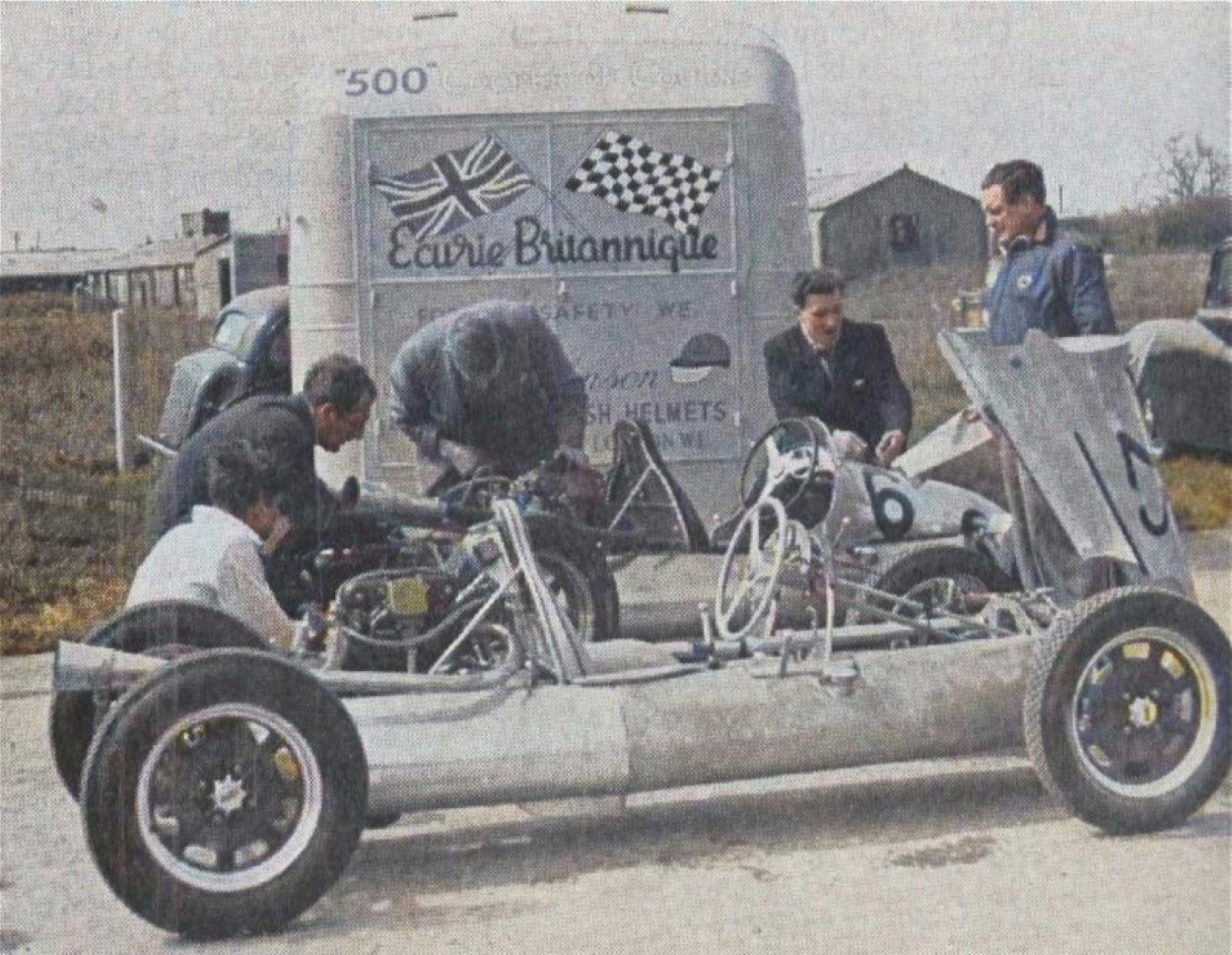

These two main teams were joined on their adventures in Luxembourg by the newest Formula 3 squad made up of Coopers: Ecurie Britannique. Following the successful formula implemented by Ecurie Richmond, the team was founded as an equal partnership by two drivers: John Coombs (who would become known for his role as team owner in the 60s and 70s) and Alan Rippon. The team had left its first mark at the Earl of March, when Coombs managed to take third place overall in the race. Both drivers would attend the race in Luxembourg, and each was equipped with one of the brand-new Cooper/Norton MK.VI.

Another interesting name that would drive a Cooper car in this race was Les Leston, who entered a Cooper/Norton MK.VI under the Leston’s Motor Accessories badge. The driver had already been on the F3 circuit since the end of 1949, but it was only in the middle of 1951 that Leston’s name would become better known in motorsport. First with his good results on the track and then with his huge auto parts store in High Holborn (a street located in the heart of London) – tough international fame for Leston, however, would only be reserved for the end of the 50s, when the driver would be part of the squads of Cooper (F1 and F2), Connaught (F1), BRM (F1), and Aston Martin (WSC).

Speaking of famous drivers, Kieft Racing Cars once again highlighted Stirling Moss as the sole representative of the factory team for Luxembourg. In reality, the story is a little more complex than that: despite having a large shareholding in Kieft, Moss decided, from 1952 onwards, to run as a semi-privateer, in parallel with the automaker of which he was a businessman. Moss used this subterfuge as a way to gain access to the company’s infrastructure, without being tied to the bureaucratic structure of a business (in this case, a team). This also allowed Moss greater freedom of action, with one of his first acts as an independent modifying his own Kieft chassis, with the help of designer Ray Martin.

This meant that Moss’ CK51, which was already a prototype by design, became an even more peculiar and particular car for the driver, fully adapted to his own needs. Therefore, it is impossible to define this car as a Kieft CK51 or C52 – therefore, for teaching purposes, the author will define the Stirling Moss car as a CK51/52, being a hybrid of new parts built on an old chassis. For the race in Luxembourg, Stirling Moss made its entry under the banner of the “S.C. Moss” team, the same the driver was using in the British F3 events since the beginning of the year.

Other British drivers, who would race as privateers and have Kieft cars at their disposal, were Don Parker, with a recently delivered Kieft/Norton CK52 and Charles Headland, in an older CK51, also equipped with a Norton engine. Each of the drivers had so far in 1952 achieved two victories (Parker at Gosport and Boreham, and Headland, at Ards and Ibsley), proving the strength of the Kieft cars for that year.

Mackson Cars was also in a position to make its first international adventure, sending a squadron of the new cars to the Grand-Duchy. The duo formed by the experienced F. Libre and F3 driver, Ken Wharton, and the young promise Arthur Gill, would be responsible for taking the newborn car of Hampshire to its baptism of fire, in the center of Europe. Both cars were entered under the auspices of Arthur, being registered as part of the A.D. Gill Team.

Concluding the list of British drivers in the race were some other well-known and interesting names: Sir Francis Samuelson, third place in the 1951 Luxembourg GP, returned to the Grand Duchy with his Cooper/Norton MK.V, hoping to once again surprise the young drivers on the grid; And another veteran of the 1951 race, Austen May, also put his name on the entry-list, lining up one of the few Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV remaining in top-level European races.

However, the most interesting British privateers were Ninian Sanderson and Peter Collins. The first would be known for his two class and one overall (1956) victories at Le Mans, moments which made Sanderson one of the biggest names in Scottish motorsport (his home country). However, at the beginning of 1952, Sanderson was still a modest Formulas driver, dividing his duties between some F2 races (for Ecurie Ecosse) and F3 (as a privateer). Lastly, the driver had achieved some good results in 1952 before the race in Luxembourg, such as victory in two Scottish national events (the Royal Scottish Trophy and the Turnberry 500cc Meeting), both with a Cooper/Norton MK.VI.

Peter Collins was another of the young players on the grid, despite already having some international luggage behind him. Until the 1952 Luxembourg GP, the driver had already participated in 3 international F2 races (at the time, the main category in world motorsport) for HWM, in addition to the countless appearances in 500cc F3 GPs, since the driver’s first experience in the category in 1949. As his companion for the Luxembourg Grand Prix, the driver would take the only J.B.S. remaining on the grid.

But as had happened in 1951, the continental response to Luxembourg’s call had also been heard, and representatives from some countries around (and within) the Grand Duchy also accepted the invitation to attend the event.

The most interesting of these teams and privateers was the Dutch Beels Racing Team with its distinct orange cars. Two vehicles were detached to the Beels effort, one for the company’s creator, Hercules Alexander “Lex” Beels, another for his friend and business partner, Pim Richardson. Each would drive a Beels/J.A.P., one of several clandestine copies of the early-production Coopers, which had been developed by Lex himself in partnership with the designer and journalist Jan Apetz, with support from the Dutch company Avio-Diepen B.V. Also coming from the Netherlands was the 1951 Luxembourg GP veteran, George Buijtendijk, in his old, but faithful, Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV.

Ecurie Luxembourg would try its luck again in the 1952 race, with Jos Zigrand perfecting some design details of the ZIG, which continued to be equipped with a J.A.P. engine. Once again, it would be up to Paul Ries to guide the machine, carrying the colors of the Grand Duchy in the race. Also having only one representative in the race was Denmark, with Kaj Hansen making the trip from the Nordic countries to Luxembourg. Hansen would drive an Effyh equipped with a J.A.P. engine, one of the most popular 500cc F3 cars.

From Belgium, three competitors came: Paul Swaelens, who would line up one of the rare Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV equipped with long-chassis (a specific variant of the vehicle that allowed this Cooper to participate in F2 and F3 races, depending on the engine configuration); Robert Kahn, who would take a vehicle of unique construction, the Kahn/BMW; and the italo-belgian Mauro Bianchi (yes, the younger brother of Lucien), who, in one of his first interactions with single-seaters, would drive a Belgian-made Telna/J.A.P.

France also line-up 3 entries for the race. The main one was André Loens, who, despite racing with a British license and being part of a Franco-British team (the Ecurie Flandres/Purewell Motors), was born in France – and therefore was French in practical terms. Loens would join the ranks of the Luxembourg GP in a newly received Kieft/Norton CK52. He would be followed by the Ecurie Française representatives: Henri Morisi, in a JB/J.A.P. III, and Jean Dabere, in a D.B. Panhard ‘500’.

The big disappointment was on account of Germany, which in the initial entry list had managed to bring together three representatives, driving three different machines: Walter Komossa, in his already well-known Scampolo/BMW, Helmut Glöckler, in a D.B./BMW and Adolf Lang, in a Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V. However, when activities began in Findel, only Lang would attend, with Komossa and Glöckler later withdrawing their entries – and therefore leaving Germany with only 1 representative in the event.

As in 1951, activities on the track began a few days before Ascension Day, with veterans from other editions of the Luxembourg GP having the opportunity to rediscover the old Findel circuit – while the newcomers, so to speak, had their first glance of the challenging track. Even so, the challenges and problems of these first training sessions were “well distributed” across the grid, not differentiating brand or driver skill.

For example, Stirling Moss looked far from his usual form, being affected by a torrent of problems with his Kieft. It is worth mentioning, however, that Moss was not driving his usual car in this race, having damaged his personal machine beyond repair at the Brussels F3 GP, just over a week earlier. Therefore, the pilot had ‘borrowed’ just for this race a production-based Kieft CK51, that belonged to Derek Annable. Constant failures in the braking system compromised almost all of Moss’ timed sessions, with poor lap times being the clear signs of another difficult weekend for the driver in the Grand Duchy. Peter Collins also had his share of problems, frying his engine in the first free practice session.

However, other drivers did very well on their return to Luxembourg. Ecurie Richmond, led by Alan Brown and Eric Brandon, had managed to set some of the best marks in preliminary training, with the pair consistently achieving the best times of the day. Ken Carter also did very well in the session, although he was constantly harassed in qualifying by André Loens (Kieft) and Ken Wharton (Mackson), the two big positive surprises in the practice.

Between training and free sessions, the race day finally arrived (May 22nd). Once again, more than 25 drivers had accepted the A.C.L.’s invitation, offering a wide range of origins, models, colors and sizes of cars, with the Luxembourgeoise public well entertained with this multicolored parade. As had happened in 1951, the race would be divided into a round of preliminary heats, which would define the drivers who would compete in the final race of the 1952 Luxembourg Grand Prix.

12 cars lined up on the grid for the first heat: Adolf Lang (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.V); Alan Brown (Cooper/Norton Mk.VI); Alan Rippon (Cooper/Norton MK.VI); Charles Headland (Kieft/Norton CK 51); Don Parker (Kieft/Norton CK52); Francis Samuelson (Cooper/Norton MK.V); George Buijtendijk (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Henri Morisi (JB/J.A.P. III); John Coombs (Cooper/Norton MK.VI); Ken Wharton (Mackson/Norton); Ninian Sanderson (Cooper/Norton Mk.VI); and Pim Richardson (Beels/J.A.P.).

The first of the 12 laps of this heat began as soon as the checkered flag flew over the Findel circuit. Don Parker jumped into the lead, with Alan Brown hot on his heels. In third place was Charlie Headland, who was holding off John Coombs and Ken Wharton, two drivers who wanted to prove themselves in the race. While the first lap passed practically cleanly in the front group, further back it was a different story: in the final curve (the connecting harpin between Neudorf and Treves streets), Pim Richardson lost control of his car and spun, with the machine nearly collecting Adolf Lang and Ninian Sanderson’s cars in the process. However, only the Dutchman’s car suffered the consequences of the accident, with both Lang and Sanderson continuing in the race.

On lap 2, Alan Brown took the lead, which was regained by Parker on the following lap. That’s because Brown, in a moment of inattention, missed the harpin’s breaking point, and ended up crashing on the outside of the curve. The damage from the accident was serious enough to force Brown to withdraw from the race.

This left Don Parker in a comfortable position, which, in the end, turned out to not be as comfortable as it seemed – because the now second placed, Ken Wharton, in his Mackson, was at a relentless pursuit pace, certainly surprising a good part of the field. Lap after lap, the driver gradually reduced Parker’s lead, with Wharton’s approach being a matter of when.

Further back, another battle captivated the public: recovered from his incident with Pim and Lang on the first lap, Ninian Sanderson had managed to regain contact with the field, and in the following laps, an incredible climb in positions had taken him into contention for third place, against Charlie Headland and John Coombs. Despite Coombs having the early lead, Headland’s Kieft seemed the most balanced car of the trio, and it wasn’t long before the driver took third position.

Meanwhile, Wharton ephemerally took the lead on the 9th lap, after pulverizing the 3-second advantage that Parker had managed to build in the first few laps. But Parker wouldn’t let himself be beaten that easily, and soon the driver regained his position as leader, with the Mackson right behind.

But the biggest emotions of the race were reserved for the last lap: Parker and Wharton were separated by just tenths of a second on the 10th and 11th laps, and, in the last corner of the 12th lap, Ken tried to launch his final attack to take the lead. Mackson and Kieft shared the harpin; and it was the West Midlands car that did best. Don Parker crossed the finish line with a total time of 22m19s, just 1 second ahead of Ken Wharton.

And the decisive moments of the heat didn’t end there. Just a few seconds behind, John Coombs and Charles Headland were dueling for third place (Sanderson had already dropped out of contention, having lost precious seconds in the previous laps). Headland looked like he already had the third place under his belt, when, rounding the harpin, the Kieft’s right suspension gave way, puncturing the car’s fuel tank. Taking advantage of his rival’s problems, Coombs overtook Headland, taking the third spot just meters from the finish line.

If the first heat already offered memorable moments in the history of the Luxembourg GP, the second would also have its place, with fifteen other drivers taking their respective starting positions: André Loens (Kieft/Norton CK52); Arthur Gill (Mackson/Norton); Austen May (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Eric Brandon (Cooper/Norton MK.VI); Jean Dabere (D.B./Panhard ‘500’); Kaj Hansen (Effyh/J.A.P.); Ken Carter (Cooper/Norton MK.VI); Les Leston (Cooper/Norton MK.VI); Lex Beels (Beels/J.A.P.); Mauro Bianchi (Telna/J.A.P.); Paul Reis (ZIG/J.A.P.); Paul Swaelens (Cooper/J.A.P. MK.IV); Peter Collins (J.B.S./Norton); Robert Kahn (Kahn/BMW); and Stirling Moss (Kieft/Norton CK52).

Authorization to start was given and it was the Franco-British André Loens who jumped ahead, followed by Stirling Moss, Eric Brandon, Ken Carter and Les Leston. In the second lap, the order of this field remained the same, with the only difference being Leston falling a little behind in the race, due to gearbox problems. It didn’t take long for the Leston’s Motor Accessories driver to be overtaken by the drivers behind him – in this case, Arthur Gill and Peter Collins.

The fight for the lead would become even more selective from the 3rd lap onwards, when Loens had mechanical problems (engine chain) and was forced to abandon the race. This saw the race lead fall into the lap of Stirling Moss. However, the Briton was heavily harassed by the constant attacks of his compatriot Ken Carter, who threatened Moss’ tenuous lead with each new move. What both drivers didn’t notice was the stealthy approach of Eric Brandon, who, in a coup-de-main on the 4th lap, took the lead (the result of a beautiful double overtake).

For a few laps it was Brandon who dictated the pace of the race, until the Ecurie Richmond driver was forced to abandon the contest due to a broken drive shaft. Once again, the leadership changed hands, and this time, Ken Carter was the man responsible for guiding the flow of cars that circulated around the Findel circuit.

Before the ninth lap, however, it was Stirling Moss who was once again leading the pack. But this leadership almost didn’t last just a blink of an eye. While passing some backmarkers, Moss almost collided with the Cooper of Paul Swaelens, as the latter driver tried to recover from a spin in the harpin. A quick reaction from Moss was enough to avoid an accident, and the driver carried on.

Apart from this scare, nothing would hinder Stirling Moss’ journey to victory in his heat, taking the checkered flag after 23m17s of racing. 4 seconds behind crossed the second place Ken Carter, who was another of those who had to take evasive measures from Swelens’ slow car. Rounding out the podium was Arthur Gill, giving the second good result of the day for the Mackson cars.

The big surprise of this heat was Paul Reis, with the ZIG/J.A.P. from Ecurie Luxembourg. The car performed much better in 1952 than 1951, and Reis put in some very competitive laps, much more regularly than some of his better known and more experienced continental rivals (such as Hansen’s Effyh or Dabere’s D.B.). Not surprisingly, Reis would be ranked as the best non-British driver in the heat, achieving a well-deserved 6th place in this race. But it didn’t matter now what the drivers had done in the qualifying heats, as all eyes were on the final race of the 1952 Luxembourg GP: it was time for the great show, which would feature 12 of the best cars and drivers at the site.

Only British drivers qualified for the final race, with starting positions based on the best average speeds achieved in the heats. Heading the list was Don Parker, who was joined in the front row by Ken Wharton and John Coombs. Charles Headland and Stirling Moss completed the second row, with Ken Carter, Ninian Sanderson and Alan Rippon in the third. In the 4th row, Sir Francis Samuelson and Les Leston lined up, with Peter Collins and Alan Gill giving final numbers on the grid, in the 5th row.

When the flag waved for the last time in Luxembourg, all the drivers gave their all – those were the 25 laps that would sum up an entire week of training and preparation, with the opportunity to win an international victory within reach of everyone involved at that moment.

Les Leston was the name at the start. Having an almost perfect reaction time, the driver jumped from 10th position to 1st in a couple hundred meters, leading the pack in the first corner. Stirling Moss also had an excellent first lap, with the Kieft driver following Leston’s slipstream into second place. Don Parker and John Coombs were unable to react quickly enough to stop these incursions, and the most they could do was place themselves behind the pair who were now leading the race.

Moss, however, was not satisfied with the second position he had just achieved and headed towards the lead of the race. At the end of the first lap, it was he and his Kieft CK51 who opened the standings, followed promptly by Parker, Leston, Coombs, Carter and Rippon. Ken Wharton, who had performed so well in the qualifying heat, was forced to withdraw early on, due to problems with the Mackson’s exhaust pipe.

The race had turned into a free-for-all, with the drivers constantly swapping positions. At the opening of the second lap, for example, it was Don Parker who was leading, with Ken Carter (second) and Stirling Moss (third) in hot pursuit. 3rd lap, and new change: Les Leston had moved up to first, with Don Parker and Stirling Moss still in the podium area. However, it didn’t take long for Parker to fall out of the top-3, after his car began to have gear problems.

Once again Ken Carter placed one foot on the podium, following the duel that developed between the leader Les Leston and the now second placed Stirling Moss at a short distance. Moss seemed relentless in his determination to retake the lead, but a problem with his Kieft’s magneto meant the Brit canceled his plans on lap 6 – a long stop in the pits and return to the race in a modest ninth position almost spelled the end of any hope that existed of a new international victory for Moss’ resumé.

Without Moss, the duel for leadership was reduced to the battle now between Les Leston and Ken Carter. Both pilots were equipped with Cooper/Norton MK.VIs, so there was no technological advantage for one or the other. The tenuous advantage held by Leston shrunk gradually, until it finally disappeared. Carter and Leston overtook each other several times between the 7th and 11th laps, providing a spectacle worthy of a GP for the Luxembourgeoise public.

Between the 12th and 15th lap, a brief moment of lull in the battle for the lead, with Ken Carter provisionally taking the lead during this period. However, it was at this point that the confrontation reignited, with Leston retaking 1st position before the start of the 16th lap.

Further back, combat also developed in an interesting way. Peter Collins had taken third place just before the 10-lap-mark, with Don Parker (who, despite his gearbox problems, continued in the race), John Coombs and Charles Headland close behind. However, as the laps went on, Parker’s problems became more serious, and the driver ended up being overtaken by Coombs.

Don Parker’s losses in the race could be greater, as when the driver was about to be overtaken by Headland, the Lincolnshire driver had clutch problems, which forced him to go directly to the pits, instead of attacking Parker’s dying Kieft. Peter Collins observed these problems from a distance (despite the driver being one of those fighting against an untimely gearbox), with John Coombs doing little to threaten the position of the future F1 star; So weak was Coombs’ performance at that moment that he allowed Parker to approach again – who surprisingly managed to overtake the Ecurie Britannique driver!

For the lead, the battle seemed to have come to an end: Carter had pushed his car to the limit, exhausting all his strength, while it appeared that Leston would not give up another meter of ground in the race. With this deadlock, Leston and Carter remained firm in their positions until the end of the race, with the Leston’s Motor Accessories driver crossing the finish line first, at the end of the 25 regulatory laps, with a total time of 45m48s. Some excitement remained in the race when Ken Carter’s car shuddered near the finish line due to a gearbox collapse. But the checkered flag was too close for this to be nothing more than a small scare, with the driver guaranteeing a 1-2 Cooper finish. Giving final numbers to the best classified in the race was Peter Collins, on his first international podium in a single-seater race.

As a closing note to the 1952 GP, it is worth mentioning a minimally curious case: originally, Les Leston had not managed to qualify for the final race, only having the possibility of competing in it due to problems with Adolf Lang, who, technically, was the 12th classified driver. The German had not been able to get his car ready in time to line up on the grid, and Leston was then invited to join the 11 other vehicles on the starting line – in the end, this proved to be an incredible stroke of luck for the driver, generating the best of the possible results.

Luxembourg GP: A Tale of Motorsport

The Luxembourg GPs of the 1950s were, ultimately, valuable experiments by the Automobile Club du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, in its quest to host increasingly important and relevant events on the European motorsport scene. A clear learning curve can be perceived, spanning the events from 1949 to 1952. The step forward, when the race was first opened to F3 cars, in 1951, was without a doubt the crucial moment of this journey, in which the possibility of transforming the Luxembourg GP into a synonym of national prestige (and not just another race, of the dozens that already existed throughout Europe), became true.

However, the A.C.L.’s next step forward, to bring real GP cars to Luxembourg, never materialized. This is not due to the institution and popular desire, which were able, for the first time, to taste competitions that truly brought together talent and competition in one place. But rather due to factors linked to the Grand Duchy’s own infrastructure, which was finally inserted into the context of a more united, stronger and developed Europe in the early 1950s.

Findel airport, which served so well the purpose of being the ‘home’ of Luxembourg motorsport at this time, became its Achilles’ heel as the 1950s progressed. By the end of 1952, Findel had become an important hub of the Grand Duchy’s economic system, being one of the main entry and exit points for the country, which was now part of the European Coal and Steel Community, the union that would be the embryo for the current E.U.