Celebrating 55 years of the 1969 European Hill Climb Championship crown, where the Ferrari 212E Montagna finally gave Scuderia Ferrari its first title in this motorsport discipline, Sports Car Digest presents its readers with an in-deep story of this mythical vehicle, in a form of a detailed summary of its development and the complete analysis of the 212E racing record.

In this second part, the reader will participate in the moment of truth in the 212E project: the first race valid for the 1969 European Hill Climb Championship, in Montseny (Spain). Afterwards, we will follow the journey of Scuderia Ferrari throughout the first part of the championship season, with stops in Germany, France and Italy. Not everything would be roses for the team throughout these races, with the 212E demonstrating some weaknesses that could be fatal to the Scuderia’s objectives for 1969.

VI CARRERA EN CUESTA AL MONTSENY

EUROPEAN HILLCLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP (ORGANIZED BY THE RACC)

Although the pre-season tests gave very positive signs regarding the 212E Montagna, these only served as a base parameter for the upcoming races of the European Hill Climb Championship. So far, Ferrari has faced a somewhat disjointed effort from rival teams, with the Abarth cars being the only ones to demonstrate any possibility of challenging the Maranello manufacturer’s power. However, the time had come for representatives from Alfa-Romeo, Porsche and Ford to also join the fray, promoting the great duels for European peaks.

The first official stop on the 1969 European Hill Climb Championship calendar would be the Montseny massif, located in the interior of the Catalonia region (Spain). Since 1967, an integral part of the European championship, the hill climb had become one of the best events of the tournament, deservedly recognized for its exemplary organization, having as wallpaper the scenic landscape of the interior of Spain. The route, 16,300 meters long, was mainly composed of medium-speed zig-zags and areas of high acceleration, having as the starting point the city of Sant Celoni. The climb progressed, following the geographical features of the massif till the small village of Santa Fé de Montseny, where the finish line was located.

The 1969 race would be sanctioned by the F.I.A., with organization delegated to the Real Automóvil Club de Cataluña (RACC) – as the race was also part of the Campeonato de España de Conductores de Velocidad (the Spanish national racing championship, which also included hill climbing events). So, it was to be expected that in addition to the foreign pilots, a large contingent of Spanish drivers would attend the race, interested in scoring points in their respective national ranking.

After the 212E’s excellent performance at Volterra, both Ferrari and Schetty had concluded that the car was in perfect mechanical conditions, with almost no modifications being carried out by the team on the car during the interval between the two races. On the other hand, Abarth returned to appear on the entry-list, with Ortner’s 2000 SP Cuneo, in addition to the group 4 privateers, now definitively homologated for competition.

Activities in Montseny began on Friday, with free training activities continuing until the following day, Saturday. On each day, each pilot would have three chances to perform a climb, thus having access to certain parameters regarding the track conditions. In the end, there was a consensus among the pilots that this would be a climb without major problems from a mechanical point of view, since, for the 1969 edition, the entire length of the route had been repaved. The biggest concern was the weather, with broken clouds giving a dull tone to the entire Catalan region

The fastest Spanish driver in the qualifying sessions was Alex Soler-Roig, a well-known figure within the European motorsport scenario. With 9m55s9/10, the Spaniard achieved a surprising third place in the overall timing of the two days, driving a Porsche 907. However, it was again Ortner and Schetty who stole the show. Despite all Johannes’ efforts to get close to Schetty’s marks, the Austrian could do little to prevent the Ferrari from excelling on yet another mountain: Peter had recorded a magical time of 9m20s4/10 in the first sessions – as comparative term, Ortner had set as his best time 9m46s9/10.

The cloudy Saturday would give way to sunny Sunday, and with it, the promise of a great race at Montseny. While the cars were released individually, Scuderia Ferrari waited in line for its turn to be called to the starting line. Peter Schetty had great confidence that he could improve his time even further, despite certain parts of the circuit being wet, especially in the section close to the finish line, in Santa Fe de Montseny. However, expectations looked set to come true as drivers in other categories also improved their times despite the adverse weather conditions.

Schetty would start before Ortner, leaving the Austrian with all the pressure of having to beat the time set by Ferrari. And the Swiss was merciless with his strategy: on an almost perfect climb, Peter pulverized Montseny’s historic record, achieved by Gerhard Mitter the previous year: the German’s 9m30s3/10 had been surpassed by the 9m12s4/10 of Schetty and his Ferrari. Johannes Ortner would not have stood a chance against such a dominant performance, and, in the end, Ortner had to settle for a distant second place, being almost 30 seconds slower than the Ferrari in the race.

To make the day even more bittersweet for Abarth, the almost guaranteed third place was lost by the manufacturer just a few steps away from the finish line. Soler-Roig, defying the opposition of two Abarth SE010s (of Biscaldi and Taramazzo) in the Group 4 class, had managed to hold on to third place in the general classification, once again placing a Porsche on the podium of a hill climb event.

ALPEN BERGPREIS BERCHTESGADEN

EUROPEAN HILLCLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP (ORGANIZED BY THE A.V.D.)

Two weeks after the championship opener in Montseny, teams and drivers headed to the second stop of the season: Berchtesgaden, the picturesque town located in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. With just 5,890 meters long, the Roßfeld-Berchtesgaden hill climb was the shortest of the whole championship, with the fastest track times generally being around 3 minutes and 20 seconds. The official track record had been set the previous year, by none other than Gerhard Mitter and his Porsche Bergspyder (with a time of 3m16s).

However, there was a second, even more impressive mark achieved by Mitter in training for the same race, who had supposedly completed a climb in a time of 2m55s – considered at the time the unofficial Berchtesgaden record. However, it would not be the German’s records that marked the 1968 edition of the event. Without a doubt, the most striking memory of that edition was Ludovicco Scarfiotti’s tragic accident, which cost the charismatic Italian driver his life. Therefore, there was no lack of incentives for a good performance by Peter Schetty and Ferrari for the 1969 edition: the ambition of breaking the record on another track, while at the same time paying tribute to the driver who had won two championship titles for the manufacturer during the 60’s.

But, when the team arrived to settle in the small German town, it seemed that the plans were going to go down the drain – literally. An incessant rain fell over the Bavarian region, turning the path where the cars would pass into a rapid. According to what was reported in the press at the time, when the first training sessions were held at the location, on Saturday (7th), more than four days of uninterrupted rain had already washed the zone; which gives the general picture of the situation at the event.

Despite the adverse weather conditions, the public showed up in reasonable numbers to witness this first session. There were also reasons for this: the unpredictability of the weather could open the door to some surprises, being the best opportunity so far that an outsider had to beat the 212E. The main threat to Ferrari and Schetty was the works-Abarth ‘Cuneo 2000’ of Johannes Ortner, but some privateers, such the Scuderia Brescia Corse and the Asashi-Pentax Team, with Luigi Taramazzo and Helmut Leuze, respectively (each equipped with an Abarth 2000 SE010) could also surprise as well. Alfa-Romeo also appeared in the championship for the first time, through semi-works Alfa Romeo Deutschland. The team would line up two T33/2s prepared for hill climb races, counting with a line-up composed of two experienced German drivers in this discipline: Michel Weber and Anton Fischaber.

At first, it seemed like some surprise might actually materialize, with both Weber and Fischaber demonstrating the potential of the new car. However, Ferrari’s 300hp engine was enough to offset any advantage of the Italo-Germanic team, which could count on a maximum output of ‘only’ 265hp. It was expected that Saturday’s training, in the constant rain, would provide excellent parameters for the drivers of what to expect for Sunday – but, once again, the situation did not follow the original script.

The teams were stunned to wake up on Sunday and discover that the rain had finally stopped – to give way to snow! A light white layer had covered the entire Bavarian region, which would certainly disrupt the entire course of the competition. Despite considering the possibility of postponing (or even canceling) the race, the Automobilclub von Deutschland (A.V.D.) decided to go ahead with the activities. A small improvement in the weather helped the track cleaning activity, with only a slight delay in the schedule. For the race, each driver would have to make two climbs on the 5,890-meter route, with the sum of the times defining the winner of the race.

The prototypes were to start first, allowing, even with a subsequent worsening of weather conditions, the pilots in the main category could at least have a chance to make a climb. The Ferrari, Abarth and Alfa drivers did their best in the first heat, knowing that this could be the heat that would define the weekend. Unsurprisingly, once again, it was Schetty who did best, with a spectacular time of 3m10s2/10. 5 seconds slower was second place Weber, with Taramazzo’s Abarth just behind.

As the pilots made their way back to the base of the Roßfeld mountain for the start of the second heat, the weather worsened again. A dense fog covered the track, and coupled with some showers, it became another complication for the drivers. But Schetty, unchanging in his stance with Ferrari, seemed not to care about the inconveniences of the weather. Despite doing a slower second lap, in 3m17s, the driver had once again managed to be the fastest in the battery, sweeping the weekend in the German Alps.

Michel Weber and Luigi Taramazzo also confirmed their positions obtained in the first heat, completing the podium in Berchtesgaden. The disappointment was due to Ortner, who, after achieving the fifth best time in the first heat, had dropped to sixth at the end of the combined times; It was a result to be forgotten by a driver, who, at the beginning of the season was aiming to be one of the contenders for the title race.

As a final addendum to this race, it is worth mentioning a sharp deterioration in time after the prototype races. Conditions became so dangerous that, after protests, some of the classes had the second heat canceled for safety reasons.

XLV COURSE DE CÔTE DU MONT VENTOUX

EUROPEAN HILLCLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP (ORGANIZED BY THE FFSA)

After the shortest race of the year, it was time for the longest race on the European mountain climbing calendar. The historic Course de Côte du Mont Ventoux, which, in 1969, was in its 45th edition. Located in the Provence region, Mont Ventoux was the mecca of mountain running in France, due to its long heritage of races in the discipline, dating back to 1902. In addition to this longer history, the place had a more recent importance: Mont Ventoux had hosted the first F.I.A.-sanctioned European Hill Climb Championship event in 1957.

This historic race would be won by a fellow countryman of Schetty, Willy Daetwyler. Peter, therefore, aimed to place himself in the pool of rare Swiss winners of the hill climb, which included, besides Willy, only one other driver, Heini Walter (winner of the 1963 edition). Ferrari was also another that coveted success on the traditional French event, as the manufacturer had (till 1969) achieved only one single victory in the general classification of the race in its history: in 1962, with Scarfiotti.

Mont-Ventoux was not only feared for its great length (21,600 meters), which strained the drivers’ memory to the maximum in trying to remember each bend and kink of the route, but also for its unpredictability. Due to the long distance between the start and the finish points, it was not uncommon for weather conditions to be completely different at both ends. Add this fact to the huge amplitude of the track, roughly 1,600 meters, between the lowest point (the village of Bédoin) and the highest point on the route (the peak of Mont Ventoux) and you understand why the track was so (in)famous.

Scheduled for June 22nd, all the main teams in the European Hill Climb Championship have committed to participating in the event: Scuderia Ferrari with its 212E for Peter Schetty; Abarth & Co., with two Abarth 2000s for Johannes Ortner and Arturo Merzario (recently promoted to the main team squad for the Hill Climb tournament); and Alfa-Romeo Deutschland, with its T33/2 driven by Michel Weber and Anton Fischhaber.

Unlike the race in Berchtesgaden, the weather conditions during the race weekend in Mont Ventoux proved to be minimally suitable for promoting a motorsport event. The pilots only faced some residual difficulty in the final session of the ascent, when mountain conditions were constantly changing: for example, on Sunday, the day of the official race, it was reported that visibility close to the finish line did not exceed 15 meters, due to a thick fog that enveloped the mountain peak.

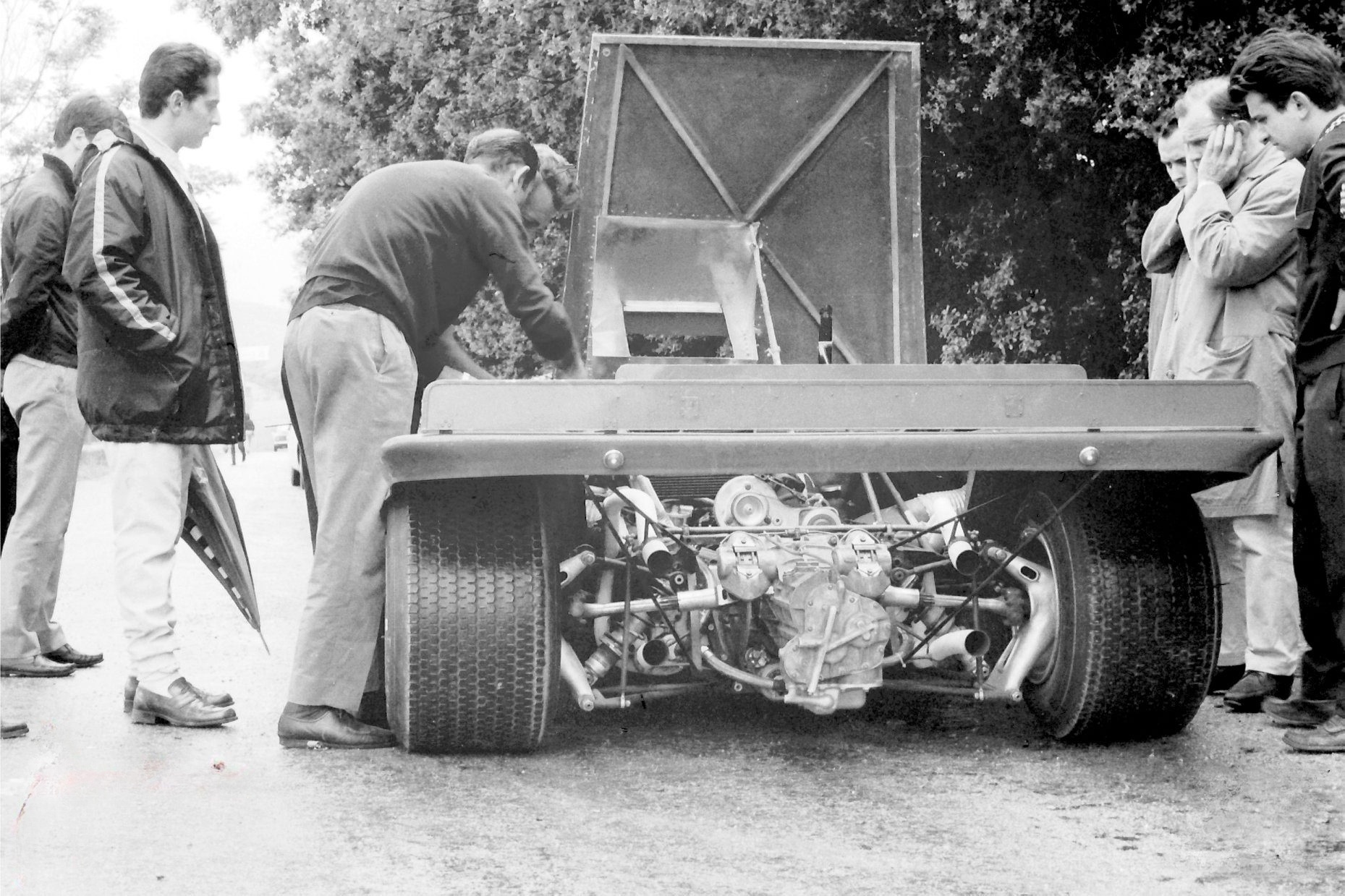

Even if the weather did not present itself as a setback, this did not exempt the teams from having some other problems: Abarth was now facing strong opposition from Alfa for the position of second force in the championship, with the T33/2 consistently proving faster than the 2000 SE010. Ferrari, on the other hand, was going through great trouble, with mechanical problems putting the team’s perfect campaign to date at risk. The main one had to do with the 212E’s floor, which was beginning to give way after the exhaustive sequence of races that the car had been subjected to in the preceding weeks.

For unknown reasons, which could range from neglect or even inattention, the team failed to notice the cumulative wear on the vehicle, with the consequences unfolding at Mont Ventoux. Without the floor, essential components of the car were unprotected from the action of stones and other debris on the ground – things that are not uncommon in hill climb events. For example, during Saturday’s training, Schetty had complained several times to the team that the vehicle’s gearbox was rubbing against the ground, running the risk of damaging an essential mechanism beyond repair.

To get around the problem, the Scuderia mechanics present at the scene built a temporary protection on the lower part of the car, with the aim of preserving the vehicle at least until the end of the French event. Due to these problems, Schetty, who would have two opportunities to make the climb (like all the other drivers in the field) would risk everything in the first heat – as the Swiss had doubts whether the car would even survive this first run.

Even with these improvisations and problems, Ferrari had confidence in Schetty to triumph once again in the championship. Starting before the Abarth and Alfa, Peter tried to once again put on a gala display with the Ferrari: the driver had been extremely fast, especially in the initial and intermediate part of the climb. Despite having to reduce his pace a little near the summit of Mont Ventoux (due to the previously mentioned problems regarding visibility), the Swiss once again set an absolute record in a mountain climb.

Once again defeating a mark established by Porsche the previous year, Peter Schetty completed the almost 22 kilometers of the Mont Ventoux climb in 10m00s5/10, a spectacular mark in itself, and which is even greater when compared to the conditions of both the Ferrari and the track at the moment.

This left little room for the cars behind, with Abarth and Alfa now knowing that the fight between both manufacturers would be for second place. At the end of the two heats, it would be the cars from the Bologna manufacturer who would do better. Arturo Merzario continued his string of good results, which started in the Italian Hill Climb Championship, being the second fastest driver of the day with 10m33s5/10. Close behind, Merzario’s teammate, Johannes Ortner, who, recovering from his disappointing performance in Berchtesgaden, reached third place in Mont Ventoux. Both Firschhaber (4th place) and Weber (12th place) could do little to beat the Abarths in the event.

XXIX CRONOSCALATA TRENTO-BONDONE

EUROPEAN HILLCLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP (ORGANIZED BY THE A.C.I.)

After the exhausting sequence of races, which had started with the Volterra stage almost two months earlier, the teams would finally have time to do a retrospective analysis of their performance so far. The inter-season break, which comprised the three-week hiatus between the Mont Ventoux and Trento-Bondone races, was a welcome breath for the exhausted European Hill Climb championship teams.

While Abarth and Alfa were looking for solutions to try to get close to Peter Schetty’s Ferrari, the Scuderia’s first task was to solve the problems that had almost cost the team the victory in the Mont Ventoux race. The 212E would be submitted to an extensive remodeling and restoration program in Maranello, with the car, in addition to receiving the necessary reinforcements on the floor and chassis, undergoing other major mechanical and aesthetic changes.

The clearest of these was undoubtedly the presentation of a new body for the 212E, which applied new aerodynamic refinements (for example, the headlights were definitively deleted, eliminating the “fat” that still remained on the vehicle). The Scuderia’s engineers also took advantage of the time available with the car to also contribute to the remastered project, increasing the maximum output of the Tipo 232 engine to something close to the 320hp. But, as always, the modifications were based on mere studies and guesswork, and only on the track, this new package of updates could be truly tested.

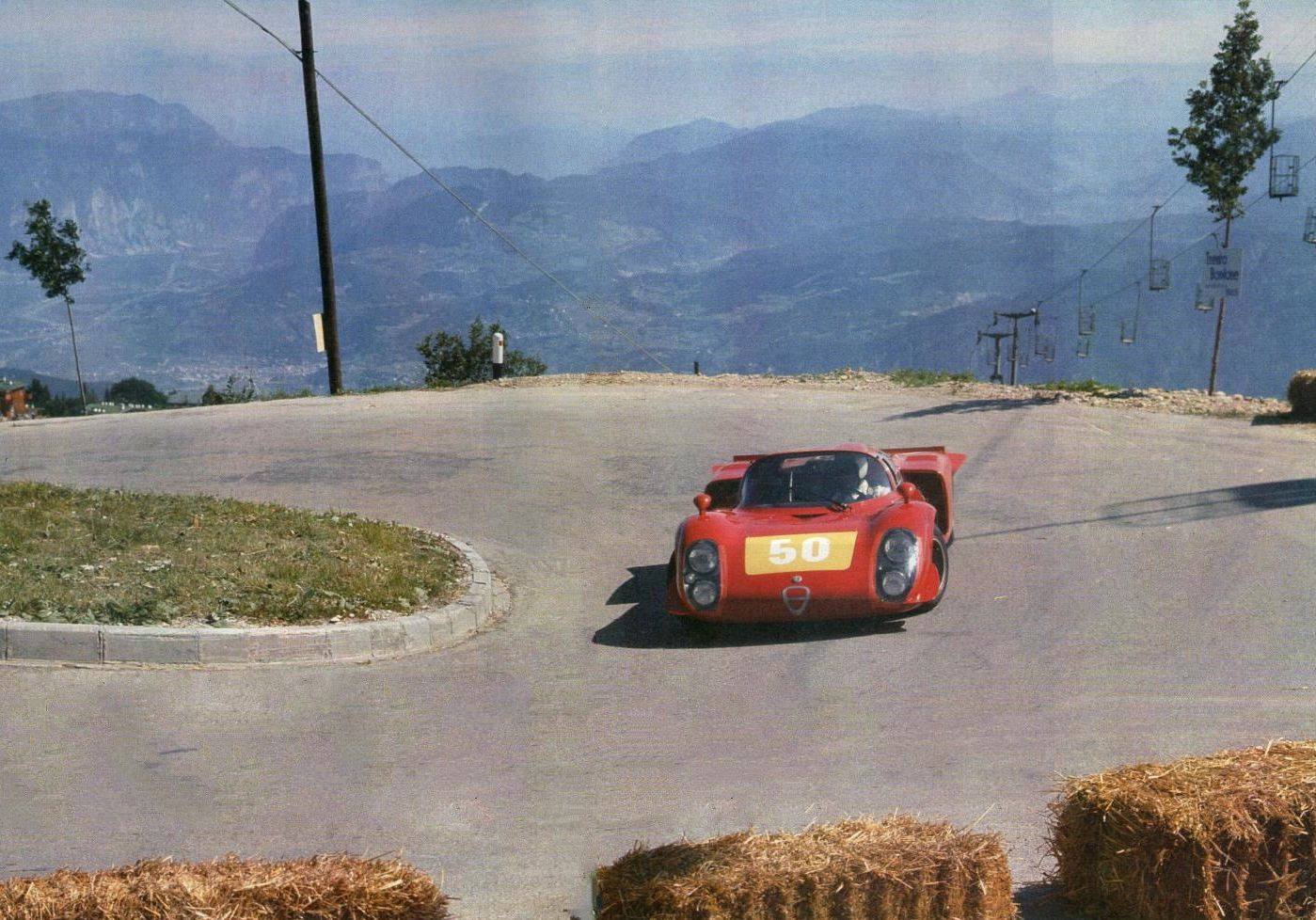

Organized by the Automobile Club Trento in collaboration with the ACI, the Cronoscalata Trento-Bondone, the 4th stage of the 1969 European Hill Climb championship, was recognized as one of the most technical climbs on the entire calendar. More than 160 curves, bends and kinks composed the route, where only the cars with the greatest acceleration could fully develop their engines. Furthermore, the tortuous climb of 17,300 meters, with a positive ascent of 1,375 meters, was in itself a challenge for any pilot.

Due to the popularity of hill climb races within Italy, contests of this type attracted a large pool of entries – and, in a race as revered and well-known as the Trento-Bondone, it didn’t take long for drivers to start filling the vacancies in the various categories that make-up the event. In addition to Ferrari with its revitalized 212E, the main highlights of the event were Abarth & Co., with its Ortner/Merzario duo (Abarth 2000), Scuderia Brescia Corse, with Luigi Taramazzo (Abarth SE010), Alfa-Romeo Deutschland, which Michel Weber (Alfa-Romeo T33/2), in addition to Scuderia Monzeglio, which would line up another Alfa (T33/2) for Aldo Bardelli.

The teams gathered in Trento on July 11th, when the first free practice activities began to be carried out. For the pilots, despite the omnipresent difficulty of the climb, the race promised to be easier and more accessible than the last stages of the European Championship. The Italian summer was proving to be more forgiving for everyone involved in the race, with sun and mild temperatures proving much more pleasant than the snow of Berchtesgaden or the fog of Mont Ventoux.

But it wasn’t just drivers and staff who were grateful for the weather conditions, with the machines also returning the favor. In both Friday and Saturday training, the Ferrari, with its modifications, proved to be, by far, the fastest car on the grid. In one of the training heats, Peter Schetty managed to reach the mark of 11s27m8/10, a great time, but still 10 seconds away from the track record, set by Gerhard Mitter in 1967. The second fastest driver in the classification was Arturo Merzario, 11m48s2/10, with Weber, Ortner and Taramazzo right behind.

As had happened in previous days, Sunday, the 13th, dawned sunny and pleasant. A huge mass of spectators lined up along the 17 kilometer route, from the start line in Trento to the small village of Vason, the finishing point, just a few meters from the summit of Monte Bondone. Each driver would only have one opportunity to complete the climb, which meant that any error would be decisive for the final classification.

The first cars started the climb at 11:45 am, with 2-minute intervals between each vehicle. Starting first would be the cars from Group 4, followed by those from Groups 6, 7 and then progressing to the GT and Touring cars. Therefore, since the Abarth and Alfa cars were eligible for the Group 4 and the Ferrari was in the Group 7, Peter Schetty already knew what to do when the Ferrari was called to occupy its starting position, at 12:31 pm: beat a time of 11m33s5/10, set by Merzario just a few minutes earlier.

Given the starting signal, Peter started strong, precisely contouring the various elbows and apexes of the climb. Schetty felt that the modifications made by the Scuderia to the 212E made the car even more balanced and stronger, with the Ferrari behaving in an exemplary manner through the undulations of the track. During reaccelerations, the extra horsepower made all the difference, with Ferrari following the Swiss driver’s commands.

Throughout the climb, it seemed that Schetty was competing in two races: one against Merzario, for his own overall victory in Trento, and another against Mitter, for the overall race record. At the end of the 17,300-meter climb, the Swiss had won both matches: a spectacular time of 10m58s6/10 crushed another Porsche record, guaranteeing yet another resounding victory for Ferrari in the championship. In addition to Merzario, who had been dethroned from first place by the unbeatable Schetty, the German Michel Weber was on the podium, who, with 11m43s2/10, saved another third place for Alfa-Romeo in the tournament.