This year, it will be celebrated the 79th edition of the Belgian Grand Prix, one of the most traditional and beloved races on the F1 calendar. Although the circuit of Spa, located in the heart of the Belgian Ardennes, has been the GP’s trademark throughout most of these years, other episodes and places were notable in the motorsport history of this small country. One of them took place in 1962, on an improvised circuit located on the streets of Brussels. It was the day when the Belgian capital hosted a season opener.

Spa-Francochamps is always remembered as the mecca of Belgian motorsport. Whether in its most legendary configuration, with the feared Masta Kink and the Stavelot curve, or in its current 7,004 km layout, the track will always be linked to the soul of Flemish land. But it would be a huge mistake to think that only Spa is responsible for the development of the Belgian motorsport: Nivelles-Baulers, Chimay and Zolder also had their share of contributions in more recent times. As well as the Ardennes circuit, which served as the first venue of motor sport in the country, back in the early 1900s.

However, as in almost every story, there is always an ugly duck: and its name is Heysel. The track, located in the heart of Brussels, existed for only 2 years as part of the contingent of non-championship races in F1 – being, shortly after the 1962 edition, discarded, due to safety concerns, the precarious conditions of the asphalt and the problem of traffic relocation, in the midst of the urban life of the Belgian capital .

Even so, the circuit had its little share of importance, in terms of its ephemeral existence. In 1961, for example, the track was one of the stages where the, by then, two-time world champion Sir Jack Brabham, made another of his magnificent presentations.

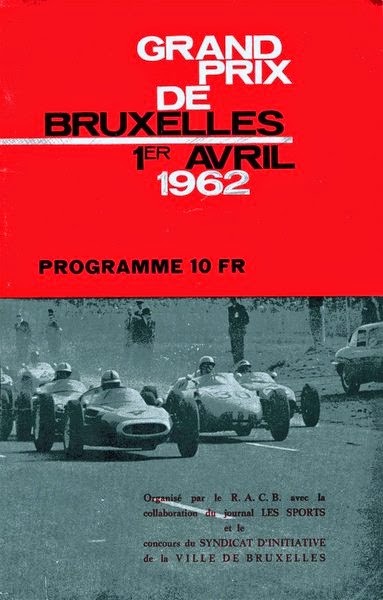

But it was in 1962 that the circuit would really reach its peak: it would be the inaugural race of the season, giving the first sample of the evolutions that the year would bring. Furthermore, the 1962 Brussels GP would have a great meaning for the Belgians: the first reason was related to the final result, which was surprising and welcomed. Secondly, it would be the last time that Belgium would host two Formula 1 events in the same year, as Spa was already preparing itself for the official Belgian GP in June.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR THE PREMIERE

The organizers of the 1962 Brussels Grand Prix were astonished when they discovered that the GP would be the first ‘official’ race for F1 cars in 1962. Even though there had already been a F1 race in Killarney in January (the V Cape Grand Prix), all the race cars present were still the 1961 models.

The official debut of the 1962 machines would then take place at the Gran Premio di Siracusa, scheduled for March 11th. But, near the planned date, the organizers claimed problems in the organization committee, causing the race to be postponed to the following weekend, the 19th. However, soon after, the race was rescheduled again, now for the 1st of May! The excuse this time was lack of money.

So Heysel’s race organizers were caught by surprise in this confusion made by the Italians. What was once supposed to be a modest event, was now going to be a season opener! But, having a safe plan in hand, the Belgians had already started preparations soon after the first sign of hesitation from the Siracusa event organizers.

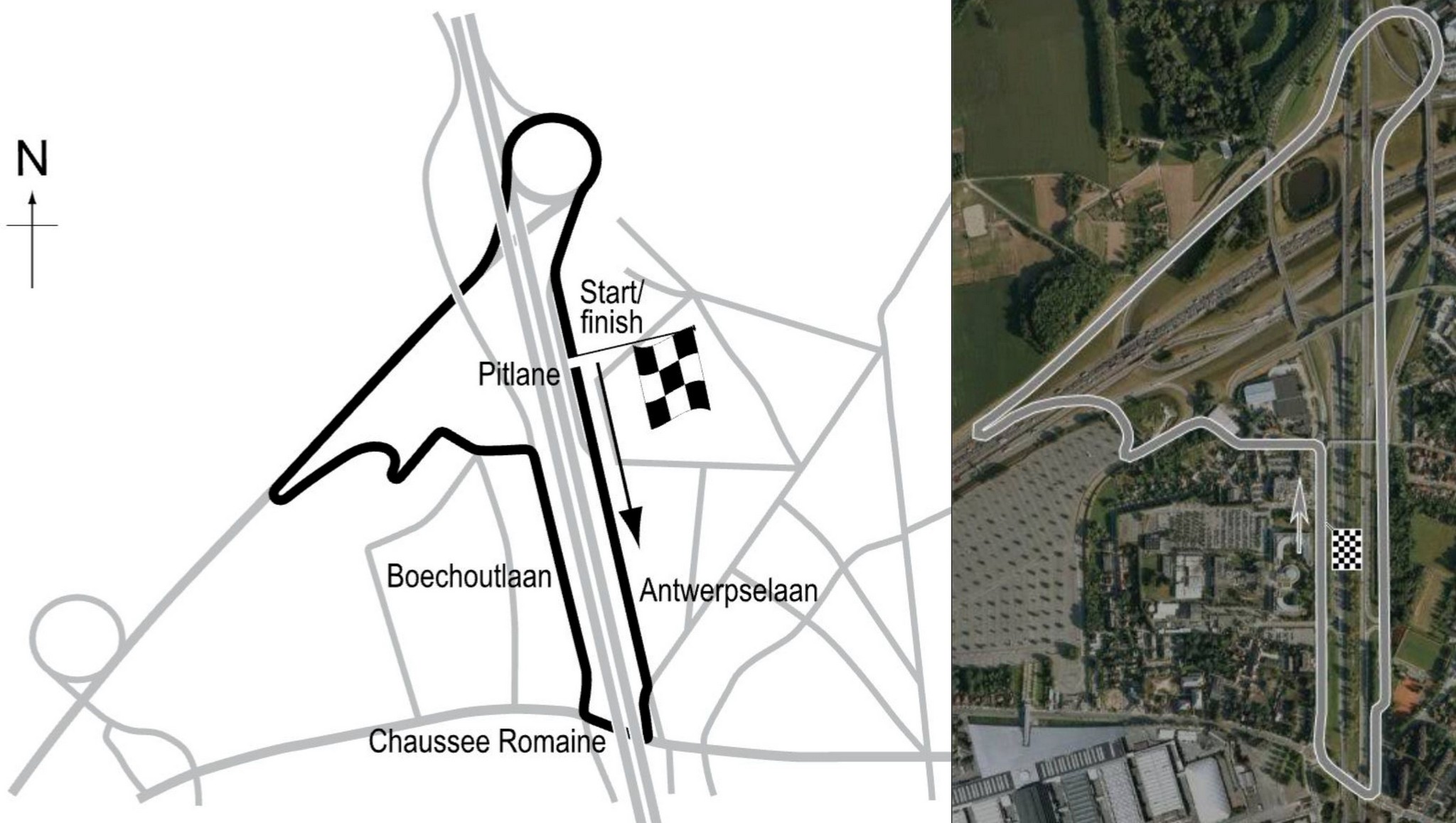

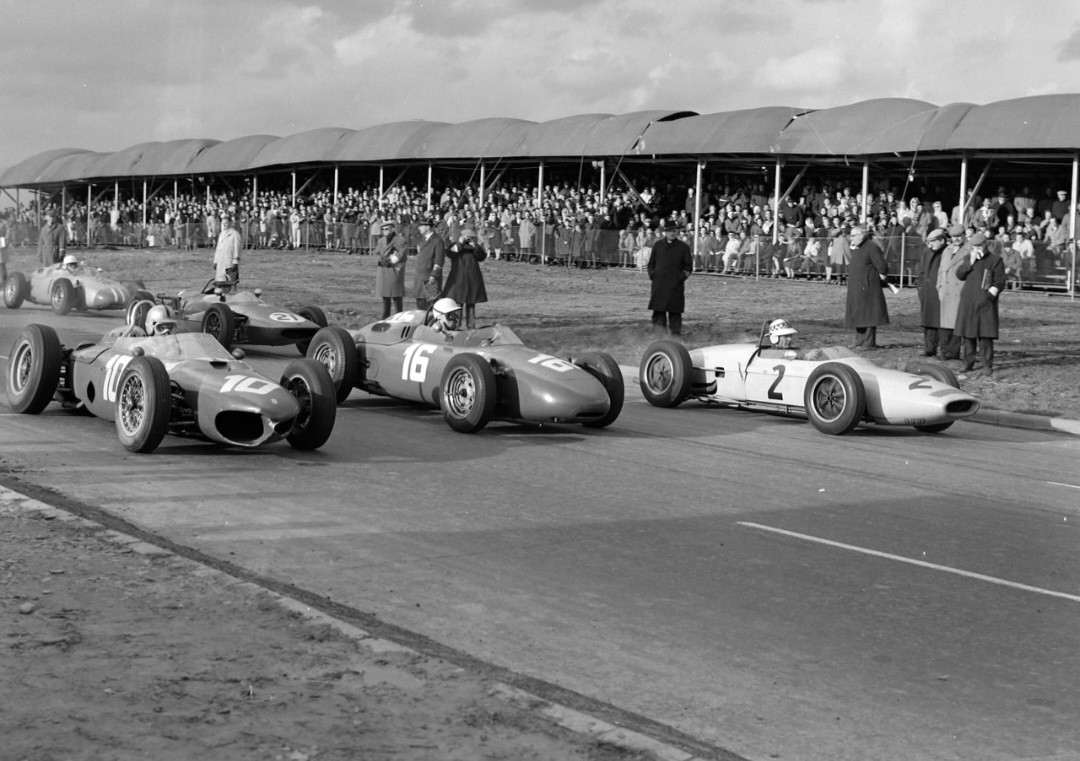

The layout used for the event would be the same as the 1961 Brussels GP: 4,525 meters long, going around Heysel Park and the residential area of Strombeck-Bever. The big difference between the 1961/62 designs was the change of the start/finish line of the track, which was previously on Boechoutlaan street. Now, it would be at Antwerpselaan, where the main stand and the entire infrastructure of the pits were also moved to.

For the rest, however, it would be a repetition of the procedures of 1961: closing the streets with straw bales, ensuring that the public did not stay in the middle of the street, that the flow of vehicles that normally passed through the site was well reallocated and that the rescuers were in place for any more serious accident. Basically the classic package of any race held on public roads in the 60’s.

THE NAMES OF THE GP

Soon after the problems affecting the running of the race in Siracusa were discovered, the Belgian organizers were quick to try to attract the best possible drivers to the race in Heysel. In total, there were 22 pilots invited to participate in the race, but with only 19 places on the grid. Striling Moss, Innes Ireland, John Surtees, Roy Salvadori, Jim Clark, Trevor Taylor, Graham Hill, Tony Marsh, Jo Bonnier, André Pittette, Lucien Bianchi and Willy Mairesse already had their places guaranteed by the organization to participate in the event.

Another 10 drivers – Masten Gregory, Keith Greene, John Campbell-Jones, Jo Siffert, Ian Burgess, Heinz Schiller, Wolfgang Seidel, Nino Vacarella, Bernard Collomb and Peter Arundell – would fight for the remaining 7 spots. The order of invitations was defined by the drivers’ most recent results, their overall race performances and, of course, their “appeal” with the public.

Moss was undoubtedly the most likely to win the GP: in addition to being the only one of the top 5 ranked drivers of the 1961 F1 championship to attend the meeting, the British would face the Belgian challenge with his feared Lotus 18/21, which had given him so many successes in the previous year.

Even though R.R.C. Walker Racing Team had already bought a new car for Moss (a Lotus 21), this vehicle would not be available for the driver in Belgium, since it was being shipped from Australia – the pilot had participated in joint F1/FJ races in the country in the first months of the year.

Who appeared with great pomp was Team Lotus, which brought a new model to the scene: the slim and elegant Lotus 24. The car was a clear evolution compared to previous models (18, 18/21 and 21), with a cleaner and more refined design, as well as being one of the first cars equipped with the revolutionary Coventry-Climax V8 (FWMV) engine.

In addition, other mechanical factors helped the car’s strong first impression with public and rival teams: a completely new chassis, a noticeable increase in the wheelbase (which helped with stability and traction); also, the entire suspension system of the car was revised, seeking a better response on the most precarious tracks, while also aiming to give the car greater resistance and strength.

The thing is that only one car of the new model was ready in time for the Brussels race; and Jim Clark was chosen to drive the machine, as he was the team’s number one driver. In contrast, his teammate, Trevor Taylor, would have to his best with a Lotus 21.

Even though Taylor’s car was from a generation before the Lotus 24, it wasn’t far behind in terms of pace. The car was upgraded to a 1962 specification, with a new FWMV type engine and a new gearbox. These updates were due to the fact that Lotus had already sold the car to Jo Siffert – but the Swiss would only be officially considered the owner of the car after the race! That is, in Brussels, the car would still run in green and yellow, and only after that it would take the red and white of the Ecurie Nationale Suisse.

BRM was also another one to send its new 1962 package for testing on the streets of the Belgian capital. The expectation was that two of the brand new BRM P57s would be shipped, equipped with the first engines made by the English team itself. But Richie Ginther had an accident just days before the race, prompting the team to come up with a last-minute stopgap. Already having guaranteed tickets for the Sunday race, BRM then invited Tony Marsh to be part of the tour to Belgium. The pilot had a private BRM but, for this race only, it would be operated as a de-facto works-car.

There were noticeable differences between Graham Hill’s car (the official) and Tony Marsh’s one (the ‘privateer turned into works effort’): the official car had magnesium alloy wheels, which were lighter than the duralamin ones, which were still used by Marsh. The cars’ exhausts were also slightly different: even though both used what is now known as the ‘organ’ assembly, Hill’s had a more efficient arrangement, which gave a slight increase in performance.

Another point was the power plants that thrusted the machines: while Hill’s car basically had the rear end redesigned to fit the new BRM V8 engine, Marsh’s poor P48/57 had to undergo emergency surgery to adapt the new ‘heart’. The operation was a success, and the car was ready to be dispatched to Brussels.

Another team that also brought news with one of its drivers was the Yeoman Racing Team, which now had the Bowmaker prefix in its name. In addition to the name change, the team decided on a total shift on its philosophy, seeking to build from scratch a new car; thus breaking its tradition of running Cooper cars.

The product of this idea was the Lola Mk4, the first F1 car built by the traditional British company Lola. The vehicle had a space frame-type chassis, which was the most advanced for F1 cars to date. It was expected that the combination between the machine and the new FWMV engines could generate good results for the team in the season.

But until the end of March, work had been slow on the Bowmaker-Lola garage. For Heysel, only John Surtees car would be ready, and even it, at a near-prototype stage. Another point that was not very auspicious was that the car would still not have the new Climax engine, because of the high demand from other works teams for the machinery. In this case, the car was adapted to receive a venerable Climax FPF, which was the only one available at the time.

Roy Salvatori, Surtees’s partner in the Bowmaker-Yeoman Racing Team, would race a hybrid Cooper T56, which mixed the chassis of a Formula Junior car with parts from other F1 Coopers. The car was also modified to accept a Climax FPF, as most Cooper T56s were equipped with BMC-XSP engines.

Yeoman’s main rival was also invited to participate in the race, and would also take two pilots to the flemish lands. The UDT-Laystall Racing Team and their traditional light green cars would also land in Brussels, represented by Innes Ireland and Masten Gregory. The team was a strange case, as, due to rankings, one of the cars was already guaranteed in the race, while the other was not. Even so, the team evenly divided their efforts, so that both cars had equal chances in the contest. The ease was that the machines were the same (two Lotus 18/21, with Climaxes FPF), in addition to the pilots themselves having a very similar pace.

Scuderia SSS Republica di Venezia (which until 1961 was known as Scuderia Serenissima) was another that also proposed to send two cars to the event – and another one that also faced the dilemma of having a car guaranteed in the race, and another not. The team, which was a personal hobby of Conte Volpi, but was managed by Nello Ugolini, would count with the services of the factory-team Porsche driver, Jo Bonnier, and the Italian rising star, Nino Vaccarella, for the event.

The Venetian team got the contract with Swede Bonnier for this race after an agreement with Porsche, which involved a small loan fee and the purchase of a Porsche 718/2 from the German constructor. Vaccarella, however, had already been a one-off team driver in the 1961 season – and now the pilot was looking to establish himself as a more regular driver, aiming for a long-term contract for the season. To achieve this objective, the Italian had in his hands another one of the numerous Lotus 18/21 FPF on the grid.

The last team to send two cars was Ecurie Nationale Suisse, who had placed its hopes in the best Swiss talents available: Jo Siffert and Heinz Schiller. The Ecurie distinguished itself by promoting the rising stars of the land located in the heart of the Alps on a world stage. Georges Filipinetti was the main investor in the venture, designating a Porsche 718/2 for Schiller and a Lotus 22 for Siffert.

As a note, Siffert’s machine was basically a one-race car, as it was Team Lotus compensation for the Lotus 21 that was to be delivered after the race (the story mentioned a few paragraphs above). The Lotus 22 was also one of the “hybrid” cars, which mixed elements of FJ with F1: the chassis was from the original FJ, but the engine was a Cosworth, with a mixture of custom-made parts, with others tuned by the team. Worthy of mention is that this was one of the first appearances of a Ford-Cosworth engine in a sanctioned F1 event; And, consequently, can be considered one of the patriarchs of the family that would dominate the sport in the second half of the 60s.

The big disappointment was due to Ferrari: the Maranello team sent to Belgium only one car, a distinctive 156 sharknose; which would be placed under the protection of the main driver of the Flemish land, Willy Mairesse.

The beautiful creation of Vittorio Jano and Carlo Chiti also underwent an update process for the 1962 season, even though it was the current World Champion machine. The suspension system was completely redone, seeking greater resistance in the car’s chassis. The car’s oil tank and battery were also rearranged, with the first being moved to the front of the car – consequently pushing the battery a little further back. Even though the engine-gearbox combination was the same as in the 1961 season (the Ferrari 178 1.5 V6 and a 6-speed gearbox), the exhaust pipe was shortened, with expectations that this would further improve the car’s performance.

Of the other teams with one car, one driver, we have the small Anglo American Team, with the experienced Ian Burgess (Cooper T53P, model known as Aiden-Cooper); Gilby Engineering, with Keith Greene as driver (Gilby/Climax FPF); and the home team, Ecurie Nationale Belge, with Lucien Bianchi (ENB/Maserati). Two other drivers would race in a full privateer effort: French Bernard Collomb (Cooper T53/FPF) and the German Wolfgang Seidel (Porsche 718/2 F4).

Emeryson was a special case: even though it was theoretically a team composed of two cars, in reality, it operated based on two independent teams: the first was Belgian André Pilette, who had his car powered by a Maserati engine.

The second was reserved for Briton John Campbell-Jones, who was taken aback by the chance to drive the car. According to what the pilot said in an interview given in 2007 to Sports Car Digest, “it was very much a spur of the moment thing”. “[…] the Emeryson driver didn’t arrive from America, so Paul (Emery) asked me if I wanted to drive his car […] It was a 1961 car and it went pretty well”.

Thus, the final list was then closed with 21 pilots, from the original 22. Peter Arundell was the first victim of the cut, as he was the pilot originally assigned to Emeryson of Campbell-Jones.

PRE-RACE WEEK: TRAINING AND QUALIFICATIONS

After the arrival of the last contingent of drivers, in the days preceding the first practices at the Heysel circuit, everything seemed to be ready for the inaugural race of the 1962 F1 calendar. The problem is that not everything works as planned in big shows – but, that time, the fault was not even of the organizers themselves, but of events that were beyond human control.

A relentless rain covered the Belgian capital for a few days, and apparently it wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon. The circuit had extremely wet parts, with puddles everywhere – but it was too late to cancel. After a delay of hours, on Friday (30), the pilots were released to do their first reconnaissance laps on the Heysel circuit.

Even though the track was practically useless for setting any reasonable time, that did not stop some adventurers from trying their luck under the downpour. Stirling Moss was one of them, trying to regain his ties with the Lotus 18/21, his old companion from so many races in 1961. Tony Marsh also dared to enter the track, trying to feel his tuned BRM for the first time. Another one who wanted to try his car was Willy Mairesse, who actually did some laps around the track, giving some joy to the few spectators who were on the circuit, on that rainy Friday.

In contrast, Keith Greene and Graham Hill were both caught in the trap set by the rain. The first, while trying to set a fast lap, suffered an electrical failure, due to water entering the Gilby’s electric circuits. Hill, on the other hand, was facing problems both with his untimely BRM V8 engine and with his own physical form (the pilot had been suffering from back pain since his participation in the 12h of Sebring, which took place a week before the GP in Brussels).

However, after that slow Friday, Saturday was expected to be a more favorable day for machines and pilots. The first signs of this were a sudden improvement in the weather – something that seemed unthinkable the day before. Even if this was a sensible change, as the track still had several wet spots, it was an opportunity that could not be wasted.

But, that joy proved to be short-lived. While most drivers were already in their cars, ready to depart as soon as the track was cleared, the rain returned, in its best inclement style. Thus, the chance to make at least one quick lap on a minimally dry asphalt disappeared, for a matter of few minutes.

Since there wasn’t much to do, it fell to the pilots to do the best they could under the present conditions. Mairesse and Moss stood out, putting times that were minimally reasonable on the soggy circuit. Clark showed that the Lotus 24 was a promising car, mainly because of the V8 engine that powered the machine. Even so, the Scotsman had problems maintaining regularity between laps, because of problems in the gearshift.

Everything was going reasonably well and without serious incidents until Bernard Collomb lost control of his Cooper, less than forty-five minutes into the session. The pilot came at high speed, until, at one of the curves of the circuit, he pressed the brake pedal too hard and the car spun wildly. The Frenchman’s Cooper T53 went directly into a wall on the side of the track, and the car burst in flames. Luckily, Collomb only got away with only minor bruises from the crash; on the other hand, his car was completely engulfed by the fire, being a total loss.

Because of that, the session was halted until the track was cleaned and cleared once again. Meanwhile, the pilots waited anxiously, watching as the clouds opened again over Heysel Park. The clock ticked, as the indecision of the meteorological conditions, now and then, affected the mood of the pilots.

When authorization was given once again for the pilots to return to their posts, however, the weather had already given its final verdict: the rain had given way to a biting cold wind, which, even though was extremely unpleasant for everyone present, was better than more water falling from the sky. Furthermore, the pilots were finally relieved to see that the track was beginning to dry out in certain parts.

So, a mini-race was formed, as everyone saw now a path to set better times. And the dispute escalated in intensity, as each new lap, the track conditions improved even more. The tenths of difference made a big difference, even more so on the reasonably short circuit of Heysel.

Jo Bonnier was the first to set a time well below the tonic that, until now, had dictated the pace of the Brussels GP: in the Porsche 718 of the Scuderia SSS, the Swede set a time of 2min06s2. But the joy of the small team from Venezia was ephemeral, when Clark and Moss poured all the power of the Lotus on the Belgian track.

The first, still suffering from problems with the gears, obliterated Bonnier’s time, dropping the mark to 2min03s1. Coming next, Moss managed to stay only two tenths behind the Scotsman, even with a clearly inferior car. Also starting to show up towards the end of the session were the two BRMs: Hill managed to get around all of his problems for now, or at least long enough to take up third spot on the grid. Tony Marsh didn’t do badly either, managing to stay in fifth.

Willy Mairesse also tried to make an appearance with the Sharknose, managing to set a time of 2min04s7. With this mark, he was the best ranked Belgian driver on the grid, in an honorable 4th position, sandwiched between the two BRMs. Bonnier, who started the session so well, would have to settle with the 6th position on the starting grid.

Further down the peloton, who was unlucky enough to be cut from the race was Nino Vaccarella. The second car from the Scuderia SSS Republica di Venezia had managed to set the 18th fastest mark, which theoretically guaranteed to the driver the right to start in Sunday’s race. But, after a maneuver by the organizers, and the fact that the two drivers with worse times than the Italian (the Belgians Pilette and Bianchi) had direct invitations to the final, Vaccarella was relegated to 20th position. It was the end of the Italian’s run in Brussels, joining the injured Collomb in the race stands on Sunday.

RACE DAY

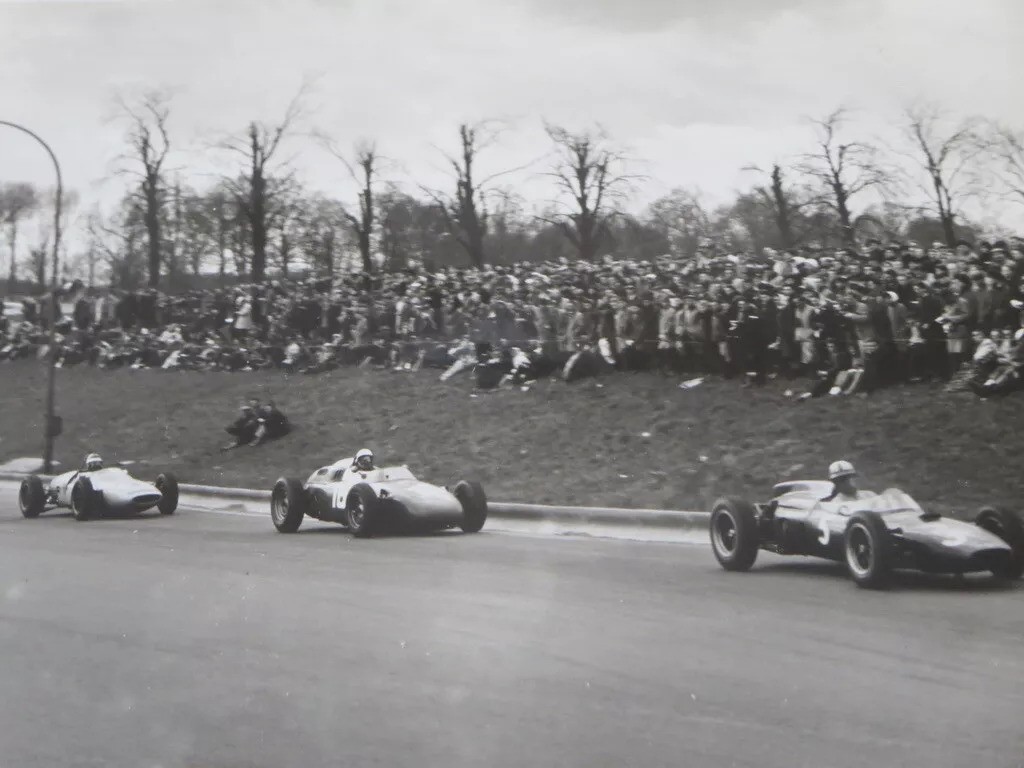

Sunday emerged like every day so far of the race weekend in Brussels: Cloudy, cold and with an uncomfortable rain. Nothing to scare away the spectators, who slowly began to take their places in the improvised stands arranged around the track. In addition to these, small groups and crowds formed at the edge of the track, where the bravest hoped to see the cars as close as possible.

The race in Brussels would be held in a 3 heat format, with each heat having 22 laps. The final result would be defined by the final positions in each heat – whoever had the lowest sum of positions would be declared the champion of the IV Grand Prix of Brussels. Therefore, it wasn’t exclusively about winning the heats, but having consistent results close to the top positions in all 3 sessions.

For the starting order, the grid of the first heat would be built based on the qualifying times of Friday and Saturday. However, for the second and third heats, the final positions of the preceding heats would be used; in other words, race two would use the final standings from race one, while race three would use the final positions from heat two.

HEAT 1

By late morning, the rain had again given way to wind in the Belgian capital. As the start procedures for heat number 1 were only scheduled for 3 pm, the track began to go through another process of light drying, at the mercy of the will of the wind.

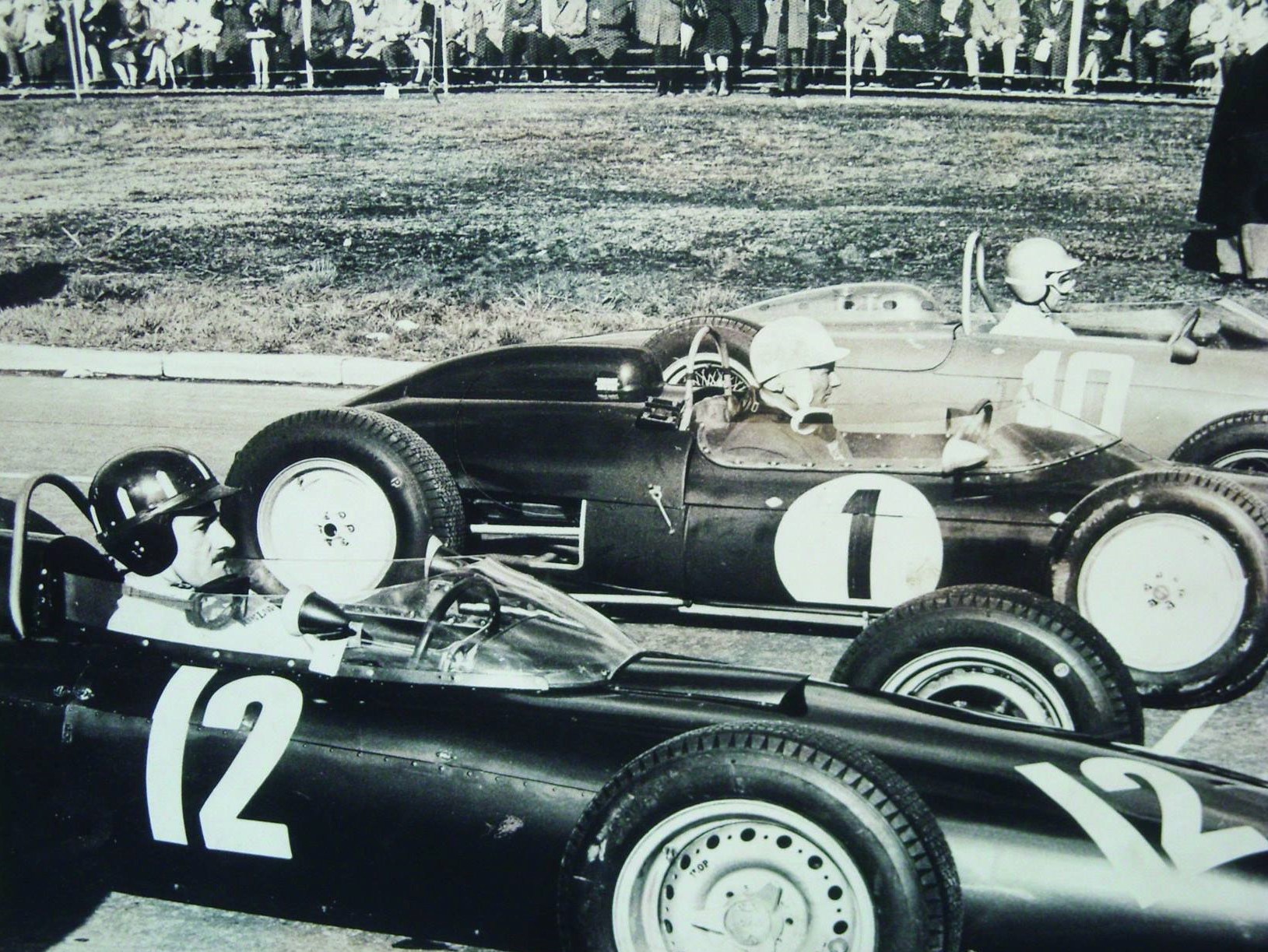

When the 19 cars were finally pushed onto the grid, the asphalt was a little better than the previous days, with only a few spots wetter, and others with bigger puddles scattered here and there – compared to the previous days, it just seemed that those were a mere detail. After the reconnaissance lap, everything was ready: cars in position, drivers gripping their steering wheels, the crowd who were both eager for the action and desperate to escape the cold wind that swept the track.

Flag lowered and the sound of the V8 and V6 echoed through the suburbs of Brussels. Stirling Moss got off to a better start and took the lead, with Jim Clark close behind. But Moss’s lead lasted just one straight: the driver overdid and entered too fast the curve that connects the Antwerpselaan and Boechoutlann straights (currently, it is the curve that passes under the A12 motorway).

The Lotus locked its tires and came to rest only at the outer edge of the corner. Clark took advantage of Moss’ slip and, as quickly as he had lost the 1st position, he had already regained it. Behind, Graham Hill and Tony Marsh were already in second and third.

Jim Clark knew he had in his hands one of the best chassis on the grid, but the problem was that the Climax FWMV engine still had serious reliability problems. When the pilot entered the last sector of the track, the car started to choke, and Clark quickly headed for the pits, preferring to save his injured machine than trying to punish it even more, in a vain attempt to finish the race. Soon after, a valve problem was discovered in the Lotus 24.

The BRMs, which started in 3rd and 5th, were now in the first two positions, at the end of the first lap. Masten Gregory was another one who also stood out, as, taking advantage of the chaos of the first lap, he managed to jump from 9th to 3rd. Willy Mairesse and ‘Big’ John Surtees were also on the trail.

Of these, it seemed that Mairesse was the driver with more ‘will’: on the second lap, the driver overtook Gregory, now climbing to 3rd position; 2 laps later, the Belgian put on another show in front of his countrymen in the stands, when, after a beautiful maneuver, the pilot snatch second place from Marsh.

Until then, Surtees had also managed to overcome Gregory, giving a beautiful display in the new Lola Mk4. Further ahead, Hill had already opened a small margin of advantage, which gave him precious moments to evaluate a possible approach by Mairesse´s Ferrari. And while a Belgian promoted moments of joy to the crowd, another one gave the first disappointment: André Pilette, on the 9th lap, had problems with his Maserati engine, and was forced to withdraw from the race.

But Stirling Moss tried to put on a show of his own, compensating in some way for this small frustration: after falling to the last position due to his incident on the first lap, he pushed as much as he could in the narrow streets of Heysel. The British came in a fulminating charge, and, after 10 laps, he already had the first positions in his sights.

But the ones that really provided good entertainment for the public were, however, the cars that came a little further back in the peloton: Masten Gregory (who was now far from the leaders), Innes Ireland and Jo Bonnier were fighting for 6th, 7th and 8th positions; while another small group, consisting of Campbell-Jones, Greene and Salvadori, followed close behind.

With 8 laps to go, Moss finally got within strike range of Mairesse’s Ferrari. The Briton didn’t want to waste too much time on the maneuver, as he was still hoping to have a chance to fight for the first place with Hill. He managed to overtake the Belgian on the next lap, but only a spectacular performance could bring Moss close enough to threaten Hill.

Further back, the skirmish between the two Lotuses of UDT-Laystall and the Porsche of Scuderia SSS would come to an end on lap 19, when Gregory’s car suffered a broken front wishbone. Ireland was right behind his teammate, and ended up being hampered by Gregory’s damaged car. Bonnier quickly reacted to the situation, and, passing both cars in a single maneuver, took 6th position.

Going back to the leaders, Moss continued his relentless pursuit of Hill, managing to reduce the gap to just four seconds. But, due to two factors, the R.R.C. Walker driver started to ease his pace in the final laps. The first was that Hill was aware of Moss’s imminent threat, keeping a controlled margin on the driver and his Lotus – the BRM still had a few horsepower hidden up its sleeve and, if necessary, Hill was ready to release them. The second is that Moss began to feel that something wrong was beginning to develop in his engine, not feeling confident enough to push his Climax FWMV to the maximum.

So Moss resigned himself to a comfortable second place, leaving Graham Hill to cross first and take the glory of the first heat for himself. The final difference between the two drivers was 5.5s; with Willy Mairesse rounding out the top three.

HEAT 2

A 20-minute break was granted to the drivers between heats. It was precious time for the teams, who, for the first time this season, would have a true benchmark on how the new technologies worked in a competitive environment (that is, of a real race).

At 4:20 pm, 15 cars lined up again on the Antwerpselaan for this second heat. Clark, Gregory, Pillet and Bianchi, who had suffered mechanical problems with their machines in the first session, would be the ones not returning from the pits. Meanwhile, Hill was in high spirits after seeing the magnificent performance of the new BRM engine.

But the British’s joy was overturned right at the start: once the flag was lowered, Hill’s BRM stalled in its place. And to make matters worse, Tony Marsh’s car also refused to start! All this because of a simple factor: the refusal to install an electric starter in the cars.

This was due to the fact that many of the teams still doubted the need for the equipment – which was still an experimental technology. It was common practice for British teams, such as BRM, Lotus, Cooper and other smaller constructors, to make their cars take the ‘stride’ in the pits; in other words, to make a push start. This had some serious consequences, that the cars could not ‘die’ between the time they left the pits until the official start – if that happened, it was very likely that the car would stall and wouldn’t go anywhere.

Both Ferrari and Porsche had already tested the mechanism in their cars, and, for more than a year, they used it as a backup, in case the engine ‘died’ in a racing situation. The discussion about whether or not the equipment was necessary heated up after a new regulation proclaimed by the F.I.A., in the middle of the 1961 season, that prohibited cars that could not start from the grid to be push-started – if this was done, the car was immediately disqualified from the race.

Therefore, when the race was held in Brussels, both organizers and drivers should already know about this new measure. In contrast, the teams, who probably already knew about this change, chose to ignore it, wanting to see to which the extent the institution would accept this breach of rules, as it was explicitly written in the 1962 FIA General Code, Section C – Formula 1, article 5: “Compulsory automatic starter with an electrical or other source of energy liable of being controlled by the pilot at the steering-wheel”.

The actions of the teams and drivers may be unjustified, but the failure of the organizers can be considered to some degree even worse, as they only had a version of the 1961 regulations in hand – and not the updated 1962, which was the only one that was valid at the time of the race.

Thus both Hill’s and Marsh’s cars were pushed indiscriminately at the start; until someone realized that this became an act subject to immediate race exclusion – but it was too late to warn the pilots. On the next lap, when the two BRMs were in the last two positions, the coup-de-grace was thrown: the black flag for both cars. It was the end of BRM hopes.

Meanwhile, Moss, Mairesse and Surtees, who shared the top positions with Hill and Marsh on the starting grid, had capitalized on the BRM mess. Mairesse had made a spectacular start, overtaking the recently condemned BRM of Hill and the Lotus of Moss at the start.

Surtees soon followed the Belgian, also managing to overcome Moss. But the Brit of the R.R.C. Walker team wasn’t going to let the other drivers take his lead that easily. After 3 laps, Stirling was in the front again, with Mairesse right on the back and Surtees falling further and further behind.

Close behind was a group consisting of Jo Bonnier, Innes Ireland and Roy Salvatori. The highlight was mainly due to the Swede, who had a spectacular race with Porsche. The car was clearly inferior to its opponents, the decisive factor being the driver’s skill and knowledge of the machine (as Bonnier drove the car for the works Porsche team in the 1961 season). Everything got even better for the Porsche driver, when he saw his fourth place become third and, a few laps later, second!

The first “promotion” in the positions came when Surtees was forced to retire from the race, on the fifth lap, after his car’s Climax FPF exploded. On the next lap, it was Mairesse’s turn to have his misfortune, when the Belgian pushed too hard and ended spinning on a puddle. So, on the seventh lap we had in order: 1st – Stirling Moss; 2nd – Jo Bonnier; 3rd – Roy Salvatori, 4th – Innes Ireland; 5th – Willy Mairesse.

A few laps later, however, it looked like Bonnier’s moment of good luck would strike once more, when Moss’s engine problems returned. The Briton had already opened a good advantage for his pursuers, but that was of no use when his engine gave its last breath of life (due to valve gear problems) – and the Moss sneakily headed to the pits in the 12th lap.

But by then, Bonnier had been overtaken by Roy Salvatori, in his hybrid Cooper. The U.D.T driver looked like he could do well with his modified car, but, incredible as it may seem, Bonnier had another coup-de-main. It’s fine to note that this time the Swede had merits in getting the overtake that guaranteed him the first place – but also, due to the engine problems that were also starting to affect Salvatori; and which led the Briton to retire on the 14th lap. That left just 3 cars fighting for the lead: Bonnier and his Porsche, Innes Ireland and his Lotus and Willy Mairesse and his Ferrari.

Mairesse, who was looking to recover from his mistake on the 6th lap, was now using in his favor the factor that could lead him to victory: his car. The Ferrari 156 Sharknose was no match for the cars of its remaining competitors, and this was soon proved in the following laps. On the 15th lap, Mairesse made his first move, when Ireland dropped to 3rd position, after a clean and bold maneuver by the Belgian. Bonnier followed shortly after, and, once again, he had to settle with the second place.

And this time, the Swede’s luck would not intervene. Mairesse took the final laps at a leisurely pace, without suffering any real response from his opponents. Upon receiving the checkered flag on the 22nd lap, the Belgian had already opened a gap of 7 seconds over Bonnier. Ireland rounded up the top three, already a good few seconds behind the top two.

HEAT 3

Another 20 minute-break and again the cars realigned on the grid, for the last heat of the IV Grand Prix of Brussels. Only 10 cars were still in racing condition – the other half of the grid having been slowly decimated due to mechanical problems and accidents. But even so, the start was given. And again, it was whoever was in second who had the best. Bonnier tractioned better and, at the end of the first lap, he was leading the field. Further back, came Mairesse, in an impetus to recover his first position.

And so he did, at the end of the second lap. The Belgian was now leading again, with Bonnier second, Ireland third, and Greene and Burgess fourth and fifth, respectively. Campbell-Jones, who had started in 4th position, had fallen behind early on, after his Emeryson refused to start (and unlike the case of BRM, this time the team used the correct procedure valid for the 1962 season. The car was pushed into the pits, so that it could later return to the race.).

After that, the race became a monotonous procession. It now seemed that the race was proceeding at an apathetic pace, almost in tune with the thick clouds and cold wind that drifted over the circuit. The only one who tried to break the melancholy of that cloudy and cold end of Sunday was Trevor Taylor. The pilot number 2 of Team Lotus, who started last in the heat, tried to put on a good show, gradually overtaking most of the cars in front of him.

By the middle of the race, the pilot was already in sixth, just behind Burgess and Greene. None of the drivers made an effort to set a stronger pace, since the result of the race was practically sealed. The fight for the overall victory was between Bonnier and Mairesse.

But it looked like that even the Swede threw in the towel in the final laps. Bonnier’s only chance was counting on mistakes made by the Belgian; But Mairesse, in this last heat, followed at a safe pace, trying not to take serious risks on the track.

Further back, Taylor wanted to give Lotus at least a little glory in this race. The pilot had taken fifth place after Ian Burgess had engine problems in his Aiden-Cooper. And, in the final laps, Clark’s teammate even managed to overtake Keith Greene’s Gilby, achieving an honorable fourth place for the valiant Lotus.

Further ahead, the situation was unchanged until the final checkered flag: Willy Mairesse finished in a comfortable first place, followed by Jo Bonnier and Innes Ireland. After this result, then, it could be none other than Mairesse to be declared the champion of the 1962 Brussels GP.

The pilot had been the most consistent in the three heats, finishing 3rd in the first, and 1st in the next two, scoring a total of 5 points. Close behind came Bonnier and Ireland, with 10 points (6+2+2) and 13 points (7+3+3), respectively. In addition to the Belgian driver’s own efficiency, it was proven that Ferrari was still the car to beat – even if both Lotus and BRM showed that, in 1962, life for the scarlet cars from Maranello would not be so easy.

But everything could change, until the first round of the 1962 F1 World Championship. And when it actually arrived, it was soon proven that pre-season could just be a simple illusion. One day you can be high up in the sky, seeing everything from the top of your pedestal; while the next, you’re back to the earth, going down in an endless pit.

A PORTRAIT OF A ERA: THE BRUSSELS GP

The Brussels GP may seem like one of those races without significance, like so many of those F1 non-championship races. But, if there’s one thing I’ve learned by reading about old reports from these races, which are basically neglected in studies of the category, it’s that each one of them has its own special charm; that each contributes in some way to the history of motorsport; and, that each one had a direct impact on the official F1 Championship – be it in a team, driver, or national auto club.

In the case of the race in the Belgian capital, its importance was fundamental for the entire development of the 1962 F1 season. Why? Well, for a number of reasons.

The first is obviously the first real test of the machines that would dominate the circuits in the 1962 F1 season. With the exception of Cooper (which would only officially debut in 62 at the X Glover Trophy, at the end of April), all the other major manufacturers in the championship attended the Brussels event, even if at different levels of preparation: Lotus, BRM and Ferrari, all sent part of their normal complements from any GP.

The second point is that the biggest losers of this race, both Lotus and BRM teams, were the ones that drew the best conclusions about their participation in the Brussels GP. The electric ignition issue, which certainly costed Hill his victory in Belgium (as the driver was clearly the most regular driver of the weekend) was an absurd mistake, which could have been prevented earlier if it weren’t for the childishness of the British teams regarding the new F.I.A. rules.

For Lotus, it was proven that even though it was a machine with enormous potential, the Climax FWMV engine still deserved a certain amount of attention, especially due to overheating and cylinder head problems. With this knowledge in hands, the improved version of the engine (the Mk.II) was presented to the teams, a short time before the first official GP of the season, in Holland. And this learning curve can be quickly summarized: 4 wins in the 9 races valid for the 1962 F1 World Championship (plus the victories in another dozen non-championship events).

Another point is that Clark’s performance in the practice sessions was enough to trigger a flood of orders for new Lotus chassis. This fitted brilliantly into the strategy defined by Colin Chapman in early 1962, who sought to throw a smokescreen over his new secret designs (among them the revolutionary Lotus 25), but who, at the same time, needed funds to finance them.

But if, on the one hand, the Brussels GP served perfectly, even if in crooked lines, for the purposes of these teams, on the other hand, the race was a great illusion for Ferrari.

Already in the next race in which the team participated, the Pau GP, it was proved that the cars were not in as good shape as expected: Ricardo Rodriguez, who had been the best qualified Ferrari in the race, finished second, more than 30 seconds behind of Moss – and just 1 second ahead of Jack Lewis, in a private BRM (which was certainly a very weak car compared to the parameters of the works teams). Even so, the team chose to turn a blind eye and paid dearly for it: it finished 6th in the official 1962 F1 manufacturers standings.